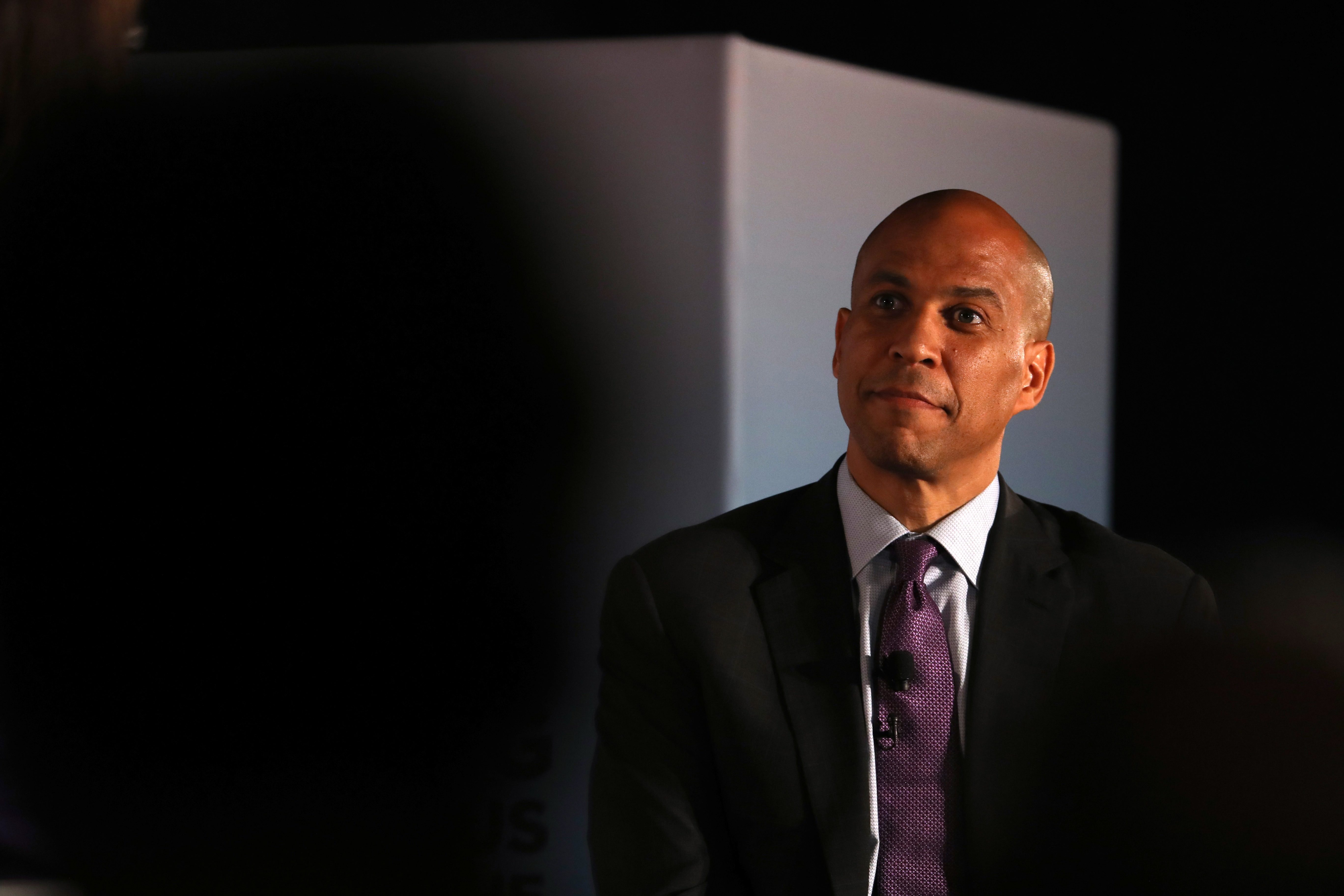

Spotlight: Cory Booker’s New Sentencing Reform Bill Is About Redemption

Editor’s Note: The Daily Appeal is occasionally examining the 2020 presidential contenders’ records, platforms, and rhetoric on issues relating to criminal justice. You can find past installments here. An article by Campbell Robertson in the New York Times today looks at the case of Angelo Robinson, in prison in Ohio since 1997 for the murder of […]

Editor’s Note: The Daily Appeal is occasionally examining the 2020 presidential contenders’ records, platforms, and rhetoric on issues relating to criminal justice. You can find past installments here.

An article by Campbell Robertson in the New York Times today looks at the case of Angelo Robinson, in prison in Ohio since 1997 for the murder of Veronica Jackson, committed when Robinson was 20 years old. A new project, Beyond Guilt, filed its first motion in June, arguing for Robinson’s release. Robinson’s first opportunity for release on parole is otherwise not until 2026 when he will be almost 50.

Advocates with Beyond Guilt met with members of Veronica Jackson’s family last summer. When they went to her sister Patricia Jackson’s home in Cincinnati, she was initially reluctant to talk to them. Two advocates, including Tyra Patterson, who herself spent 23 years in prison on a murder conviction, spoke with Jackson, at moments through tears, about “tragic mistakes, remorse, retribution and the possibility of redemption.” A week later, Patricia Jackson called Patterson. She wanted them to get Robinson out of prison.

David Singleton, the founder of the Ohio Justice & Policy Center, told the Times that Beyond Guilt was a response to the reality that too many reform proposals, including a recent one in Ohio, left people convicted of violent crimes behind. Reforms often relied on “throwing a whole lot of people under the bus,” he said. Singleton conceived of the new project “to emphasize that guilt is not an endpoint but the possible beginning of a ‘story of redemption.’”

With efforts underway to reverse the decades-long story of mass incarceration in the United States, redemption is a word that comes up in multiple contexts including sentencing reform, voting rights, record expungement, and opportunities for employment and education after release.

The U.S. incarceration rate has gone down by more than 10 percent in the past decade, according to 2017 figures, but there are still nearly 2.3 million people in prisons and jails. The pace of decarceration efforts still fails to match the scale of the problem. At current rates of decarceration, it will be 75 years before the U.S. prison population is even cut in half.

The reasons for this slow reversal are many, but one is a reluctance on the part of lawmakers to address the lengthy sentences handed down to people convicted of violent crimes. Sentence lengths in the United States are in a league of their own. The city of Philadelphia alone has more people sentenced to life without the possibility of parole than any other country in the world.

That is why a bill introduced in Congress this week by Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and Representative Karen Bass of California is so significant. The Matthew Charles and William Underwood Second Look Act would make opportunities to petition for resentencing available to anyone in federal prison who has served at least 10 years.

Matthew Charles was released in January under the provisions of the recent First Step Act. His story had attracted widespread attention leading up to his release and he was a guest of President Trump’s at the State of the Union address. Charles wrote in the Washington Post shortly after his release that the First Step Act was “a great start,” but “we have to do more. I got a second chance—and so should so many others.” Specifically, he called for Congress to pass a law that would allow all people in federal prisons a chance at release after a specified period of time, perhaps 15 years. “Some might think this idea is too lenient,” Charles writes, “but 15 years is a long time. From what I saw during my years behind bars, anyone who wants and deserves a second chance would be able to demonstrate that within 15 years.”

Senator Booker, who co-sponsored the First Step Act, met with Charles after his release and discussed the idea of second-look legislation. Now he has introduced legislation that bears Charles’s name and is rooted in the principle that individuals, regardless of their conviction, have the capacity for change.

The bill is evidence that Booker is not shying away from the meaningful criminal justice reform that many had hoped he would champion as a presidential candidate. (In a 2016 Vox interview, in response to a question about how to respond to violent crimes, Booker pointed out that the United States is “different than most places on the planet Earth in terms of the lengths of our sentences even for violent crimes.” In February, after Booker announced his candidacy, the Daily Appeal considered whether he would champion reforms addressing excessive sentences for violent convictions.)

In a statement applauding the bill, the president of FAMM (where Matthew Charles is a fellow) said: “We have to stop throwing so many people away. People can change, and our sentencing laws ought to reflect that. Lengthy prison sentences are not always the right answer, especially when someone has proven their commitment to rehabilitation. Public safety can be improved by taking a second look at those lengthy sentences, reducing them when warranted, and redirecting anti-crime resources where they might actually do some good.”

A FAMM white paper on the need for federal second-look legislation noted: “As of May 2019, more than half of the federal prison population was 36 years old or older—past the ages of highest risk. Nearly one in five people (19.2 percent) in federal prison are over age 50, well into the period of life at which we see a steep decrease in recidivism risk.”

Under the provisions of the bill, anyone serving a sentence of more than 10 years in federal prison, regardless of their original sentence, would have the opportunity to petition a judge for release after 10 years. It would also create a presumption in favor of release for anyone 50 years or older. The bill does not exclude people convicted of violent crimes from consideration.

This is significant. It takes what has become more widely recognized among advocates and academics—that sentencing reform must include people serving sentences for violent offenses—and translates that recognition into federal policy.

The legislation would also give federal judges, many of whom have criticized mandatory-minimum sentencing schemes that curtail judicial discretion and give prosecutors enormous power, a new opportunity to consider the appropriateness of a sentence in light of a person’s development since the original sentencing. In a piece for the New York Times this week, a federal judge in Florida wrote of her decision, made possible by the recent First Step Act, to resentence Robert Clarence Potts III, sentenced to life in prison in 1999 when he was 28.

Judge Robin Rosenberg wrote of the original sentencing judge’s uneasiness about the mandatory sentence he was forced to impose. But what mattered most in her decision, she said, was who Potts showed himself to be over his 20 years in prison, and who he became over the course of his 30s and 40s. He worked, studied, and set about creating a life of purpose and achievement. What struck Judge Rosenberg was that he did not do this for anyone who might review his record and consider him for release. Given his sentence, he expected to die in prison. Instead, he will be released today.

Booker and Bass’s new bill would make those opportunities for a second chance available to everyone serving a lengthy sentence in federal prison. It gives people the opportunity to go before a federal judge to be considered for release based not on who they were a decade or decades earlier and what crime they committed at that time, but on who they are today.

In an interview with the Daily Appeal, Kara Gotsch, director of strategic initiatives at the Sentencing Project, explained the significance of the Second Look Act. Numerically, she said, the bill could have an enormous impact, given that half the people in federal prison, around 82,000 people, are serving sentences that are 10 years or longer. Importantly, she said, it would also affect people “who would otherwise die in prison because of their life sentences.”

The bill is also important because unlike previous sentencing reforms, which were, in Gotsch’s words “narrowly crafted,” it “would apply to everyone.” Gotsch emphasized the importance of the bill “not singling out people who have only committed certain kinds of crimes. It is based simply on the length of sentences and that’s really significant and something we haven’t really seen anywhere, this sort of broad consideration of relief from long sentences.”

Gotsch said she hopes the Second Look Act offers a model for states to emulate. “There’s been a good trend of reform happening at the state and the federal level and because of that we have now seen the unprecedented growth in incarceration stop in the last 10 years or so. And we’ve seen a small but steady decline in the rates of incarceration. That’s a good thing, but it is insufficient. We need to do much more and make sure the reform proposals are much more comprehensive and do not leave people out, including people who have committed violent offenses and people serving life sentences because those people are likely to change over time.”

This Spotlight originally appeared in The Daily Appeal newsletter. Subscribe here.