‘Safer to Leave Them There’

How the politics of storm preparation reveal whose lives matter, and who gets left behind.

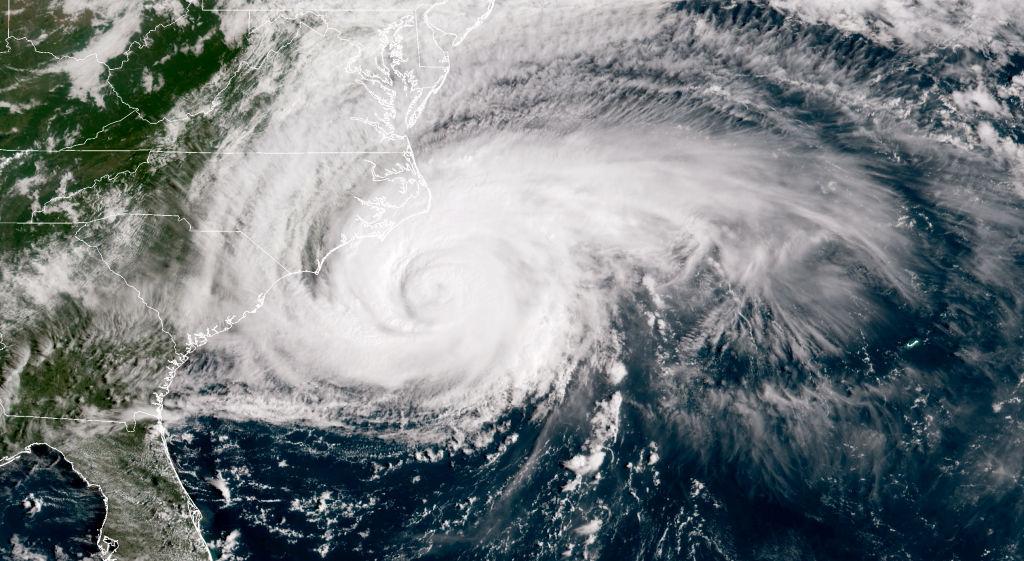

As Hurricane Florence lurches toward the Southeast, there’s another, familiar storm brewing. Right-wing gadfly Rush Limbaugh has speculated that the forecasts are just a way to “heighten the belief in climate change,” with more moderate voices warning that we shouldn’t politicize what’s likely to be a human tragedy with talk of global warming. Environmentalists argue that it’s exactly the time to politicize the event, and seize the opportunity.

Whether or not to politicize a storm, though, isn’t a question that makes a whole lot of sense. How hurricanes play out—and who they kill—are the result of deeply political choices. Officials in South Carolina have made theirs. In a press conference on Wednesday, Governor Henry McMaster urged residents that, “If you are in one of the evacuation zones, you need to leave now.” But there were no plans made to evacuate the roughly 650 prisoners at MacDougall Correctional Institution, a medium-security men’s prison in one of the five counties under mandatory evacuation. Prisoners there are being forced to stay put as the storm, recently downgraded from Category 4 to Category 2, barrels onto shore. As a South Carolina Department of Corrections (DOC) official explained, “In the past, it’s been safer to leave them there.”

It’s not the first time lives have been deemed expendable in the face of a catastrophic storm. Last year, Hurricane Maria hit an island—Puerto Rico, a territory of the U.S.—that has been under a form of colonial control for centuries. The United States diverted nearly $10 million in funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ICE, potentially hampering recovery efforts in order to help lock up people who themselves may be fleeing the slower climate impacts of droughts south of the border. This week, President Trump implied the death toll of that storm in Puerto Rico was fake news, suggesting that estimates of 3,000 people (and most likely more) killed in that storm were numbers issued to undermine his presidency.

Another obviously political choice driving storms is the one to continue extracting and burning fossil fuels, the main contributor to global warming. It’s manifestly true that climate change has helped fuel Hurricane Florence, with warmer waters allowing it to move more slowly and gather strength in the process. Yet there’s nothing inherently dangerous about storms emboldened by climate change. The real threat is in how the societies they hit are organized: Who gets hit worst, and whose lives matter enough to protect from storm surges, floods, and winds?

Jordan Mazurek, a Texas-based researcher with the group Fight Toxic Prisons, has spent the lead-up to the last several big storms to hit the continental U.S. organizing call-ins (or what he calls “phone zaps”) to pressure local, state, and even the federal government to evacuate prisoners in harm’s way. It worked in North Carolina and Virginia, but South Carolina’s DOC—which hasn’t issued an evacuation order for prisoners since 1999—is holding out. (As of Friday morning, there had been no word from the governor’s office that it intends to evacuate the prisoners, though one minimum security prison was evacuated.)

Still, even if evacuations are agreed to, that’s no guarantee they will actually happen. “We should not trust governments to do this work of their own volition,” Mazurek said. Around Hurricane Irma last year, he adds, the Florida Department of Corrections agreed to an evacuation of prisoners, but thousands of federal, state and county prisoners were left behind.

If past storms are any indication, what could await prisoners in Florence’s path is a lack of access to clean water, severely limited food supplies and overflowing toilets, conditions likely to be exacerbated if guards and prison staff don’t show up. Prisoners left behind during Hurricane Harvey in Texas last year dealt with water up to their knees for several days, and taps cut off as their prison’s plumbing gave out. One prisoner told Mother Jones’s Nathalie Baptiste, “They left us locked in an 8 by 12 foot cell for several days with feces and urine piling up in our toilets,” and that few if any arrangements were made in advance of the storm to ensure their safety.

Hurricanes aren’t the only effects of climate change that pose a threat to prisoners. As an investigation from Truthout and Earth Island Journal found, officials in Texas admitted to 23 heat-stroke-related deaths since 1998 throughout its state-operated prisons, 10 of which occurred in 2011. Seventy-nine of its 108 units lack air conditioning, the investigation found, despite temperatures that can easily exceed 100 degrees.

“Historically prisoners have not been part of hurricane planning,” Mazurek said, “until it comes time to use them as cheap labor to help with disasters.” The same prisoners forced to endure Florence may well be made to do unpaid labor cleaning up its damage, like prisoners in Florida after Irma. (Prison labor has also been a major part of California’s plans for fighting wildfires; more than 2,000 prisoners in the state are serving as firefighters, earning around $2 per day.)

“A lot of the environmental movement is increasingly focused on frontline communities,” Mazurek tells me by phone, referring to those most impacted by fossil fuel extraction and climate change. “What a lot of the mainstream environmental movement has neglected up until this point is that those exact same communities are overincarcerated. If we’re going to lift up the stories of frontline communities, we have to do the same for incarcerated people.”