Safe injection sites save lives, but most U.S. politicians are still running scared

Tens of thousands of people are dying every year. The President recently declared it a national emergency. Yet most politicians in the U.S. are still shying away from an empirically proven way to save lives claimed by the ever-growing opioid epidemic: supervised injection facilities. Sixty-six cities across the world have opened these facilities, which permit intravenous […]

Tens of thousands of people are dying every year. The President recently declared it a national emergency. Yet most politicians in the U.S. are still shying away from an empirically proven way to save lives claimed by the ever-growing opioid epidemic: supervised injection facilities.

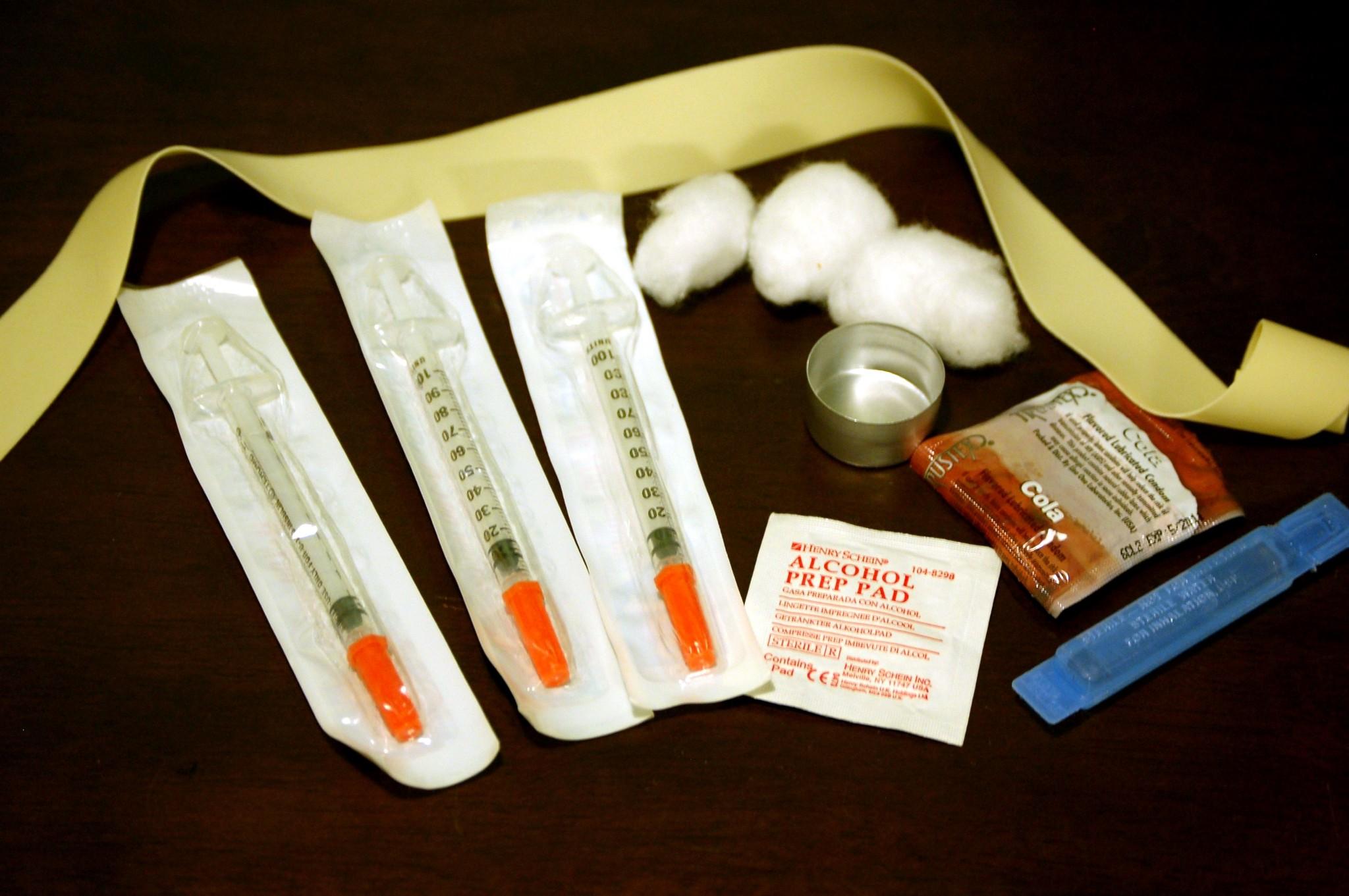

Sixty-six cities across the world have opened these facilities, which permit intravenous drug users to inject themselves under medical supervision, while providing access to sterile injection equipment, medical and social work staff, health care, and information about managing or ending addiction. Opponents argue that de-stigmatizing opioid injection at these facilities will increase drug abuse and addiction, and send a message that the government condones drug use.

To settle those fears, one need only look to Vancouver, where a government-funded safe injection facility called Insite has successfully operated since 2003. Research shows that Insite has slowed the spread of HIV, reduced overdose deaths, and contributed to the decreased use of drugs in Vancouver. Attuned to Insite’s success, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray and King County Executive Dow Constantine approved recommendations to open two safe injection sites in January. The facilities would be the first to legally open in the U.S.

“The crisis is growing beyond anything we have seen before,” Murray told The Seattle Times. “We can do something about that.”

Opposition to initiatives like that in Seattle often come from a wide array of politicians, academics, and law enforcement officials. But in Seattle, King County District Attorney Dan Satterberg has consistently supported the project. In May, Satterberg testified before supporters and opponents at a meeting of the King County Council’s Health, Housing and Human Services committee.

“I was part of the crack-cocaine response back in the 1980s,” said Satterberg. “The response was the War on Drugs. I think everyone can admit that that was the wrong response.”

In Philadelphia, leading candidate for district attorney Larry Krasner offered his support for these sites as the city began cleaning up ‘El Campamento,’ a half-mile stretch of land along the railroad where users have bought and used heroin for years. “#ElCampamento cleanup is long overdue,” tweeted Krasner. “But we can’t just sweep opioid crisis from one spot to another. Supervised injection facilities work.”

In spite of the Seattle project’s approval in January, actually opening the sites has proved to be an uphill battle. On Thursday, county officials announced that an initiative to ban the creation of safe injection sites received enough signatures to make it on the ballot.

Vancouver’s Insite has also faced strong opposition over the years, in spite of its success. When the program began, the Canadian government granted Insite an exemption from the law that would otherwise criminalize drug use at the site. But in 2006, when conservative Stephen Harper was elected Prime Minister, the new administration tried to repeal the exemption and shut the site down. In a landmark 2011 decision, the Canadian Supreme Court denied the Harper administration’s attempts to interfere with Insite — thanks in large part to the large body of peer-reviewed studies examining its impact and measuring its undeniable success.

“During its eight years of operation, Insite has been proven to save lives with no discernible negative impact on the public safety and health objectives of Canada,” the Court said. “The effect of denying the services of Insite to the population it serves and the correlative increase in the risk of death and disease to injection drug users is grossly disproportionate to any benefit that Canada might derive from presenting a uniform stance on the possession of narcotics.”

As the U.S. grapples with the growing crisis of opioid overdose deaths, the body of research from Vancouver should be a welcome roadmap for lawmakers and advocates seeking answers. The data is there — politicians just need to pay attention to it.