One Rochester Cop’s Abuses Reveal A Culture of Police Impunity

If Officer Matthew Drake had faced serious discipline for his misconduct, he might not have been on duty the night of Tyshon Jones’s death.

In March, Rochester, New York, police officer Matthew Drake shot and killed Tyshon Jones, a Black man who was in the midst of a mental health crisis when police found him walking down the street while holding a knife. Drake, who is white, has since been cleared of any criminal wrongdoing and appears to have faced no departmental consequences for the shooting. But the incident followed a pattern in his career.

In the eight years before he killed Jones, Drake drove his police cruiser into a crowd of people, was involved in the brutal beating and prosecution of another Black man, David Vann, allegedly beat a police brutality protester with a baton, and drove an inebriated young woman around in his personal vehicle for 40 minutes in violation of department policy. He was issued minor reprimands for some of these incidents and kept his job.

The fact that Drake has remained on the force long enough to kill a man is indicative of the Rochester Police Department’s systemic failure to appropriately discipline officers, said Elliot Dolby Shields, an attorney who represents the family of Daniel Prude, who Rochester police killed last year. Dolby Shields represents many people who say they have suffered violence at the hands of Rochester police, including Vann, and the multiple plaintiffs in a sweeping civil rights lawsuit filed against the city in April.

The lawsuit alleges that by covering up officer misconduct and failing to discipline officers who use excessive force over a 40-year period, Rochester has cultivated a culture of violence and impunity in its police department.

“It’s not just Drake,” said Dolby Shields. “It says a lot about the city that there are multiple officers that have serious misconduct histories who are never appropriately disciplined. It creates a culture within the department that says not only is it OK, it encourages these officers to act like this.”

Drake did not respond when contacted for this story. A spokesperson for the Rochester Police Department also did not respond. In response to the class action lawsuit, the city of Rochester denied all allegations of wrongdoing.

According to an analysis of data released by the Rochester Police Department (RPD), from 2001 to 2016, the RPD’s Professional Standards Section investigated 923 civilian-generated allegations of excessive force by officers. The department’s chiefs sustained only 16 (1.7 percent) of those complaints. And even when allegations of force or misconduct were sustained, the discipline was minimal. The harshest penalties given were six suspensions, most of which ranged from one to 20 days.

In the last two years alone, police in Rochester have handcuffed a 10-year-old girl during a traffic stop, pepper-sprayed a distressed 9-year-old girl, and tackled and pepper-sprayed a woman with her 3-year-old child. Two convictions have been dismissed — and hundreds more could follow — after the Monroe County district attorney’s office notified the public defender’s office of serious credibility issues with two Rochester police officers who had previously lied under oath. Two current officers were arrested in the past few months in unrelated cases for grand larceny and driving while intoxicated. Both have pleaded not guilty.

And in March 2020, Rochester police officers laughed and joked as they pushed Daniel Prude’s naked body into the snow-covered pavement until he was brain dead. The response to his killing became emblematic of Rochester’s handling of police violence.

City officials suppressed footage of Prude’s killing for several months. None of the officers involved in his death were criminally charged, and all of the officers remain on the force. Only one, Mark Vaughn, faced any departmental charges. Vaughn, who can be seen mocking Prude and pushing his head into the pavement until he stopped breathing, was charged with unnecessary or excessive force and discourteous or unprofessional conduct.

After footage of Prude’s killing was made public in September 2020, Rochester police chief La’Ron Singletary was fired and his command staff resigned. Cynthia Herriott-Sullivan became interim chief.

In March of this year, a six-month fact-finding investigation commissioned by the Rochester City Council found that Singletary and departing Mayor Lovely Warren had knowingly concealed information from the public and taken deliberate steps to avoid disclosing the truth about what happened to Prude. In June’s Democratic primary, Warren lost her reelection bid to City Council member Malik Evans. (Evans was unopposed in this month’s general election and will assume office in January.)

Last month, Warren took a plea deal to resolve felony campaign finance and gun charges she faced and resigned from office, effective Dec. 1. Herriott-Sullivan resigned two days later (Herriott-Sullivan’s resignation was not related to Warren’s criminal case.)

In the year since Prude’s death became public, the movement to end police violence in Rochester has notched some victories, including the election of an abolitionist, Stanley Martin, to the City Council. But real, systemic change has still not arrived at the RPD, and tensions between politicians, police, and the community that both serve have only worsened.

Now, at a time when scrutiny of the role of police in American society is at its peak, Rochester will soon have a new mayor and a new police chief. It’s a pivotal moment for the city, but it’s unknown whether the new leaders will commit to transformative change.

The true sign of change would be if the city shifts from treating violent police officers with impunity — and officers like Matthew Drake begin to face consequences for their actions.

In the last decade, Rochester has been named as a defendant in at least 40 federal lawsuits accusing police officers of using violent excessive force. Those lawsuits have cost the city millions of dollars in settlements and legal fees. Yet many officers accused of severely injuring civilians remain on the force. One of them is Matthew Drake.

“Absent external enforcement, the system will not change itself,” the class action lawsuit filed in April states. “If the Rochester Police Department had a functioning system of supervision and discipline, Drake would not have been employed that night, let alone on the streets interacting with civilians — and Tyshon Jones may still be alive.”

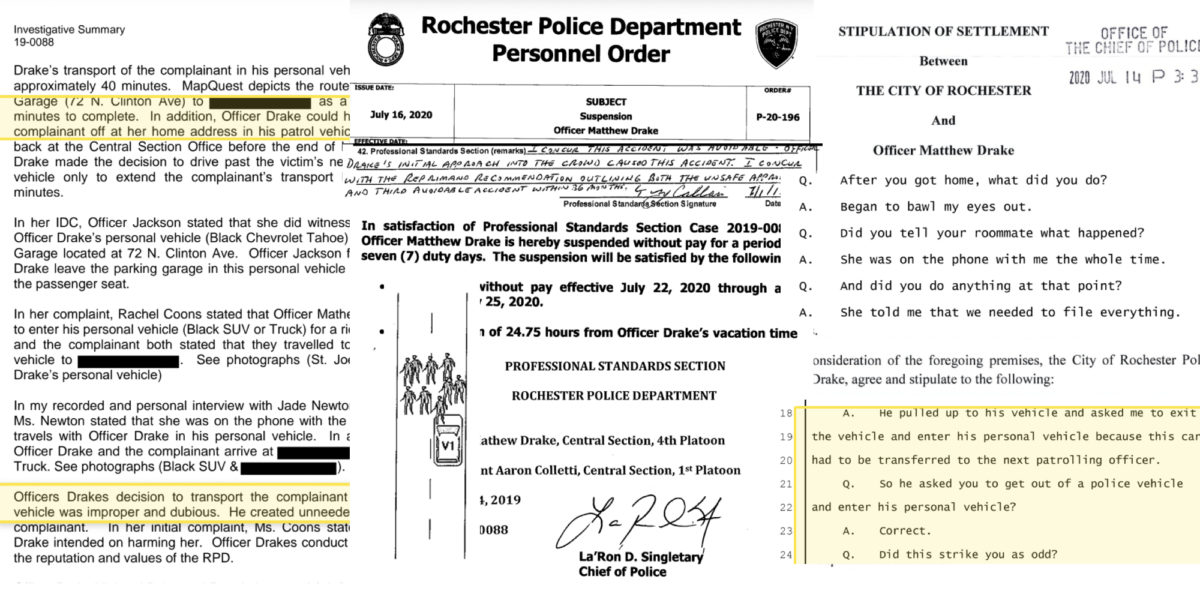

Rochester hired Drake in July 2007. Within the first six years of his career, he was involved in four avoidable car accidents, according to Drake’s publicly available disciplinary records and the city’s leading newspaper, the Democrat and Chronicle.

In 2011, according to reports, Drake drove his car through a vacant lot and hit a tree stump, damaging his vehicle. The department gave him a letter of reprimand. In 2013, Drake responded to a call about a crowd engaged in a fight. According to his supervisors, he drove his patrol car “in an unsafe manner in a crowd of people,” ultimately injuring one man. For that, Drake was also given a letter of reprimand. (Further details on the other two car accidents, both in 2009, are not included in Drake’s disciplinary file.)

Then came the 2015 beating and prosecution of David Vann. Shortly before midnight on Sept. 4, three Rochester police officers — Drake, Steven Mitchell, and Jeffrey Kester — arrived at A&Z Market on South Avenue in response to a call about a dispute.

Inside the store, the owner was arguing with a customer, 23-year-old Vann. In a lawsuit he later filed against the city, Vann says he told the officers that the owner had shortchanged him. (Like Daniel Prude’s family, Vann is being represented by Elliot Dolby Shields.) Surveillance footage shows Vann, dressed in a gray hoodie, a black jacket, and shorts, calmly speaking with officers at the front of the store.

The suit alleges that the officers did nothing to follow up on Vann’s claim that the owner had shortchanged him. Instead, the suit says, Drake asked Vann to leave the store. Vann can be seen on video slowly walking outside, then stopping and turning to face all three officers. Two of the officers approach Vann, pull his arms behind his back, and handcuff him. Vann appears to comply with the officers throughout the encounter.

For reasons that are unclear from the footage, which has no audio, officers Kester and Mitchell suddenly swing Vann’s head and body into a metal bench, causing Vann and the officers to lose their balance and fall to the ground. One of the officers wrote in an incident report that Vann had tried to pull his right arm away from the officers, forcing them to “bring [him] to the ground for stabilization,” though the footage of the incident contradicts this.

For the next minute, Vann and the officers can no longer be seen on the security camera. In his lawsuit, Vann says Mitchell fell on top of him and seriously injured him, and that Vann in turn fell on Kester, breaking the officer’s leg. Vann alleges that Drake and the other officers beat him in retaliation for Kester’s injury. The city has denied Vann’s allegations.

When the officers and Vann reappear on camera, Mitchell can be seen leading a handcuffed and disheveled Vann to a police cruiser parked outside the store. Mitchell pushes Vann against the vehicle, then grabs him by the neck. Mitchell tries to throw him to the ground, but Vann doesn’t fall. The officer then punches Vann in the face.

At that point, Drake runs over, grabs Vann, and helps Mitchell slam him against the pavement. Mitchell punches Vann in the head again, then flips the 23-year-old over and pepper sprays him in the eyes at close range. Sometime during the scuffle, Drake injures his shoulder.

Three more officers arrive on the scene and pin Vann to the ground. After several seconds, they pick Vann up and drag him to the police cruiser. Officers yank Vann’s arms over his head and frisk him. Then the video ends.

Local news footage from that evening shows Vann seemingly unconscious in the back of a police car, with his head lolling to the side as a paramedic examines him. Vann asserts in his lawsuit that EMS told officers he needed to be brought to a hospital for treatment.

But he was not brought to a hospital and did not receive treatment. Instead, police brought Vann to Monroe County Jail, where he was placed in solitary confinement for a month.

Police told the Monroe County district attorney’s office that Vann had assaulted them. So prosecutors charged Vann with two counts of assault in the second degree, one count of assault in the third degree, resisting arrest, and trespassing.

The lawsuit says that while Vann was in solitary confinement, the jail staff did not give him his prescribed medications. As a result, his medical conditions worsened, and after a month Vann was transferred to a medical treatment facility and held against his will for an additional four months, the lawsuit states.

Five months after his initial encounter at A&Z Market, Vann was able to make bail and was released from custody.

But the ordeal didn’t end there. According to Vann’s lawsuit, the grand jury was not made aware that video of the incident existed. “The mere existence of the video was material because it depicts the objective facts of the incident,” Dolby Shields wrote. That video “contradicted the allegations contained in the arrest, incident, use of force and other reports drafted and signed by” Drake and others.

A spokesperson for the Monroe County District Attorney’s Office told The Appeal the office does not comment on grand jury evidence, as it is a confidential proceeding. In court, an attorney for the Monroe County District Attorney’s Office admitted that the grand jury was not informed that footage of Vann’s arrest existed. But a judge ultimately decided that the district attorney and prosecutor in this case were entitled to absolute immunity and dismissed them as defendants.

In April 2016, a Monroe County grand jury indicted Vann on two counts of assaulting a police officer. Nearly a year later, in February 2017, the case against Vann went to trial. After viewing the video, the lawsuit says, the jury found Vann not guilty of all charges.

But the incident left Vann with lasting physical, emotional, and psychological damage, said Dolby Shields. Vann spent five months in jail for charges he was ultimately acquitted of — not to mention the amount of time and money he spent fighting the prosecution against him.

Drake, Mitchell, and Kester do not appear to have been disciplined for this incident, given that no records regarding their interaction with Vann appear in their publicly available disciplinary files. “Drake and the other officers in that incident lied in their reports, lied in the grand jury, and took it all the way to trial,” said Dolby Shields. “The Rochester Police Department should have stopped him ages ago.”

Lawyers for the city of Rochester and the officers named in the lawsuit have denied all allegations of wrongdoing in court. The lawsuit between Vann and the city remains unresolved.

In the early morning hours of Jan. 27, 2019, officer Drake spotted 22-year-old Rachel Coons outside a bar called Murphy’s Law in central Rochester.

Coons, her friend, and a man from the bar walked outside to wait for a car they’d ordered. Drake, who was alone, saw the group and offered to give them a ride, disciplinary records show.

The trio agreed. Drake dropped off the man first, then brought Coons’s friend home.

Had Drake continued heading down East Avenue for another mile or so, he would have arrived at Coons’s home, about five minutes away from her friend’s house. Instead, Drake drove to a police parking garage.

In a complaint filed against Drake, Coons said the officer had told her he needed to return his police vehicle and would not be able to drive her directly home. She assumed another officer was going to bring her home instead. But when they entered the garage, Drake pulled up next to a black Chevy Tahoe and told her to get out. He told her to get into his personal vehicle, the Tahoe, and wait for him while he returned his police car. Coons felt uneasy, but complied.

“At this point, I was very cold and scared,” Coons said in her complaint. She decided to call her friend, who ordered a car for her.

Coons stayed on the phone with her friend. She got out of Drake’s car. She tried to leave the garage, but found that the exits were blocked by gates. So she took the stairs to another floor. Then she ran into Drake.

“I was surprised to see him again and I tried to avoid him,” Coons said in the complaint. By this point, Drake appeared to have returned his police car and was speaking with a female officer. When Drake saw her, Coons said he told the female officer he had “offered to bring this girl home to try to be nice” but was now “regretting it.”

Coons openly expressed her misgivings, but ultimately followed Drake back to his car, thinking it was the only way she could get out of the garage. Coons said she asked Drake to drop her off on her street, but didn’t give him her full address out of fear for her safety. Though Coons’s home was only about 1.5 miles away from the garage, Drake drove around with the 22-year-old for roughly 40 minutes.

At some point, they passed a pizzeria Coons recognized. She told him she knew where she was. Coons said that around that time, Drake noticed she was using her phone. When Drake asked if she was on the phone with someone, she told him she had been on the phone with her friend ever since they got to the garage.

He asked to speak with her. Coons gave him the phone. Her friend told Drake her full address and said that they lived together. Drake then drove Coons home and dropped her off.

Coons walked in her door and started sobbing, she said during a deposition.

“I believe Officer Drake was intentionally avoiding my request to take me home,” Coons said in her complaint. “I was fearful that I would never make it home. … I do not believe Officer Drake would have driven me home had I not been on the phone.”

“It is of my opinion that Officer Drake intended to harm me and I was in fear for my safety immediately after entering the parking garage,” Coons added. Coons called the Rochester Police Department and made the complaint by phone later on that same day. She did not respond when contacted for this article.

In response to questions from the department’s professional standards bureau, Drake said he drove back to the parking lot because his shift was ending and he wanted to find another officer to take Coons home. Drake said he couldn’t find anyone to do it, so he did it himself. He said Coons didn’t give him her exact address and he was unfamiliar with the area, and that’s why he drove around for so long with a young woman in his personal vehicle.

Police investigated Coons’s complaint and determined that Drake had violated department policy in several ways that night. Drake failed to notify his supervisor or dispatch when he drove Coons and her friends home. He didn’t record his beginning and ending mileage. He didn’t create a job card for the transports. He failed to take the most direct route to his destination, and he failed to notify dispatch when his destination changed.

“Drake could have easily dropped the complainant off at her home address in his patrol vehicle (on-duty), and arrived back at the Central Section Office before the end of his tour,” a summary of the investigation into Drake’s conduct states. “Instead, Drake made the decision to drive past the victim’s neighborhood in his patrol vehicle only to extend the complainant’s transport by approximately 45-50 minutes.”

“Drake’s decision to transport the complainant home in his personal vehicle was improper and dubious,” the disciplinary investigation concluded.

The department gave Drake a training handout and proposed a seven-day suspension for his conduct violations. But the department ultimately settled on docking Drake three days of vacation and suspending him for four days. On July 22, 2020, Drake was suspended. By July 26, he returned to work.

Less than eight months later, he shot and killed Tyshon Jones.

Friends and family described Jones as a kind, respectful, and curious person who was deeply religious and valued helping others. They also said Jones struggled with mental illness.

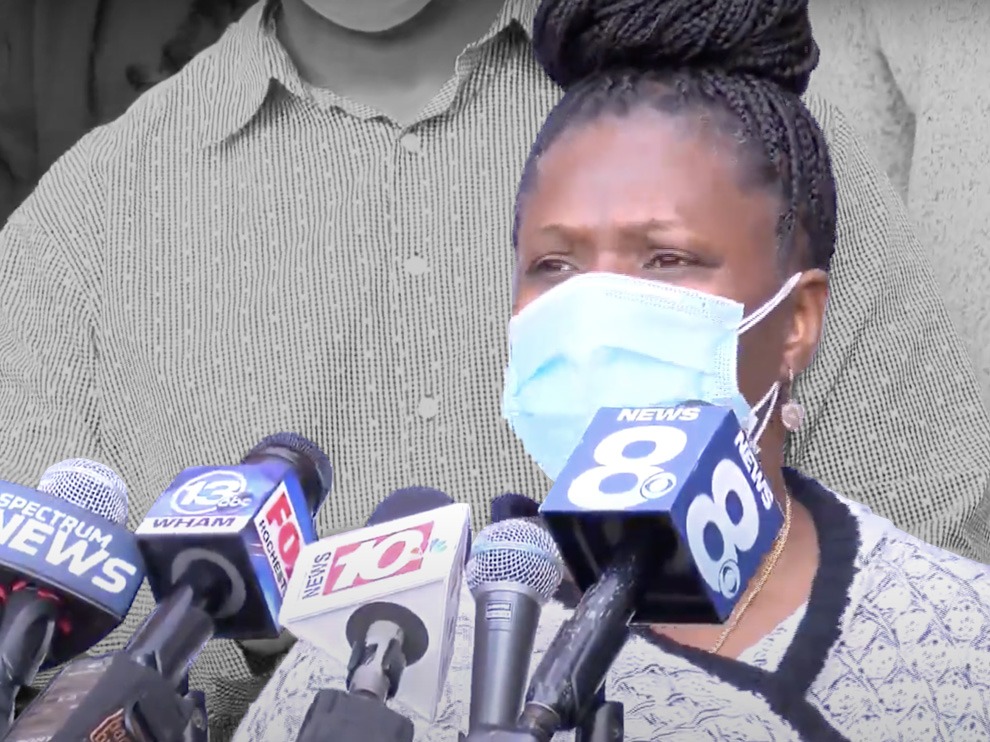

“His struggle became a death sentence, and it never should have been,” Jones’s cousin, Rev. Myra Brown of Spiritus Christi Church, said at a press conference held by the family outside the church shortly after his death.

Brown said the police did not come up with a plan to safely disarm Jones. They chose not to use pepper spray or wait for a stun gun. “He instead was gunned down, like an animal in the streets, only viewed as Black and dangerous, instead of sick and needing of mental health services.”

At the time of his death, Jones was grieving his great-grandmother and grandmother, who died within a few months of each other. Jones’s grandmother had just been buried when he was killed, said his mother, Kennetha Short.

Sometime during the afternoon of March 9, Jones left his home in Gates, near Rochester, where he lived with his mother, police said. He walked to a store, where a man bought him food. Jones, who wasn’t wearing any shoes, followed the man back to his apartment. Someone called the police to kick Jones off the premises.

Body camera video shows that Jones and the man he followed were waiting calmly outside an apartment building when police arrived. Jones said he was homeless, and police offered to give him a ride to a shelter. Jones, who was holding cookies and a bag from Family Dollar, said he liked the man he followed. He asked the officers to take him to jail and said he was “ready for y’all to take me to heaven.”

Jones soon agreed to go with the officers to a shelter and allowed them to pat him down. He got in the back of a police car with one of the Gates officers and made small talk with him. Jones asked the officer if he had a favorite song.

When they arrived at the shelter, an employee told Jones he wasn’t allowed in without shoes. In the video, Jones appears unwell, but still calm and friendly. He can be seen speaking incoherently and repeatedly referencing God and Jesus, but he is also laughing with an officer and following his directions.

The officer, Mike Furia, saw a pair of shoes in front of the building, so he picked them up and gave them to Jones. After some encouragement from Furia, Jones put them on and the shelter staff allowed him in. Furia wished Jones good luck and walked away.

Nearly 12 hours later, someone called the police about Jones again. Rochester police say that around 3 a.m., an employee from a different homeless shelter, Open Door Mission, alerted them that Jones had taken knives from the kitchen and was harming himself. The officer who responded was Matthew Drake. Drake was likely unaware of Jones’s earlier interaction with a different police department.

When Drake arrived, Jones was cutting himself with a large butcher knife while walking down Main Street. Body camera footage shows Drake telling Jones to drop the knife several times, but Jones kept walking with the knife held out in front of him. Jones said he was dangerous and told police to shoot him. After a few tense minutes, Jones began walking quickly toward Drake.

Drake then shot Jones five times, killing him.

Police say Jones was shot before nonlethal resources could arrive on the scene. The Rochester Police Department did not respond to The Appeal when asked why Drake and other officers did not have nonlethal weapons like Tasers or bean bag guns with them. Drake did not respond when asked whether he had any nonlethal weapons he could have used, like pepper spray, with him at the time of the shooting. In January, Rochester began sending social workers and mental health professionals to calls involving people who are experiencing mental health crises. But under its current mandate, the Person in Crisis team does not respond to calls involving weapons, so it would not have been dispatched to the call involving Jones.

“You killed him,” Jones’s grandmother, who did not give her name, said at the family press conference. “You shot him five times. Was it necessary? If it had been a white boy, if it had been a white girl, what would you have done? Would you have talked them down? Would you have waited for the medical people to come and tend to him? But it was my Black grandson, who you assumed was a bum. Who you assumed was a nobody.”

Rochester has plenty of police officers who, like Drake, have been a part of multiple incidents involving excessive force or serious misconduct, yet remain on the force, as the class action lawsuit against the city details.

“I think [Drake is] a perfect example of the problems with the Rochester Police Department,” said Dolby Shields. “He used excessive force, he lied about it, he wasn’t disciplined, and he went out and killed Tyshon Jones.”

Since the deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Daniel Prude, Rochester has made changes, both incremental and significant, to the way the police department functions. But police killings — and the lack of accountability for them — have continued.

Rochester has agreed to fully fund the city’s Police Accountability Board (PAB), expand its mental health response team from 14 people to 40, and cut some money from the police budget. Yet the PAB has been stripped of its disciplinary powers thanks to a lawsuit from the city’s powerful police union, the Locust Club. And while a slight reduction in RPD’s funding was finally made after the department’s budget rose continuously for years, much of the cut came from shifting oversight of animal services to the Department of Recreation and Human Services.

Evans, the incoming mayor, and the Rochester City Council face enormous pressure from the people who elected them to put an end to state-sanctioned violence and change the RPD. At the same time, shootings and homicides have risen in Rochester in the last two years, as they have elsewhere in the United States, as social and economic stresses have been exacerbated by the pandemic. While calls to change RPD have been mounting, so too have demands to stop the violence and keep Rochesterians safe.

In July, after over 200 shootings in the first six months of 2021, local law enforcement partnered with federal agencies to create a targeted policing task force, the Violence Prevention and Elimination Response team or VIPER. By the end of the 60-day operation, the task force made 101 gun arrests in Monroe County.

Some, like incoming City Council member Stanley Martin, have been critical of this carceral response to violence in Rochester. “We strongly believe if we can create environments where people can access living wages, sustainable jobs, safe education, safe secure housing, it is really going to impact their likelihood of engaging in violence,” Martin told WHAM, a local ABC affiliate.

Recently, the city did just that by signing a five-year agreement with Advance Peace, a nonprofit organization that pioneered a successful violence interruption program in Richmond, California, and has since expanded it to other cities. The Advance Peace model offers a “Peacemaker Fellowship” or monthly stipend of up to $1,000 a month to people at high risk of committing gun violence. People who enroll in the program will receive support and guidance from community mentors. They will also get help creating a “life map” to outline their goals and plans for the future and how to achieve them. The program will be housed under the newly created Office of Neighborhood Safety and will not partner with law enforcement.

“The thing I want to be very careful about is there’s a long history of cities like Rochester of backing solutions that sound nice but don’t work,” said Conor Dwyer Reynolds, executive director of Rochester’s Police Accountability Board. “I have hopes for Advance Peace, but those hopes also rest on appropriate funding.” Reynolds noted that while the city rolled out its Person in Crisis team earlier this year, versions of such a team have come and gone for years.

“What happens is someone gets killed, you fund these programs for a few years, there’s a crime wave, the programs get defunded, then it happens again,” Reynolds told The Appeal. “Is there long term commitment? Is there financial commitment? And have we learned the lessons of the past, or are we doomed to repeat them?”

Evans ran for mayor on a platform of criminal justice reform. He told The Appeal in May that as mayor he would work to identify officers who have a pattern of excessive force and egregious misconduct and “look to see what we can do to fix that.” He also said that if he were elected mayor, he would “look at functions that shouldn’t be with the police department” and consider shifting the responsibility for some of those functions, like responding to mental health calls, elsewhere. And he said he would prioritize investing in violence prevention programs and improving social services as a way to prevent more people from coming into contact with police.

“Reform is not enough,” Evans said. “We need a complete culture change. We need to have a conversation around what it is that we need our police department to do.”

Since then, Evans has frequently sounded like what he is: a politician who is working assiduously to keep all sides of a fraught debate happy. He has said he is supportive of collaborating with state, local, and federal law enforcement officials to “stem the flow of illegal guns” into Rochester. After the latest police shooting in Rochester, Evans offered condolences to the family of the man accused of robbing a dollar store whom police killed, but also said the incident “serves as a reminder of the dangers front-line workers face in our community daily,” adding that his “thoughts are with the store employees and officers who stepped into a violent situation.”

Earlier this month, Evans said he supports investing in violence prevention programs. He was one of the council members who voted to approve the city’s contract with Advance Peace.

Evans will assume power in less than two months, and the people of Rochester will then be able to see where he ultimately stands. Faced with the deaths of Daniel Prude, Tyshon Jones, and many others, as well as the repeated high-profile incidents of misconduct and brutality, the sweeping federal civil rights lawsuits against Rochester, and the community’s persistent demands for change, the issue will be unavoidable.

“For the police officer who chose to use excessive force, not only my son’s life was taken from me, my life has been taken from me,” Kennetha Short said at a press conference days after Jones’s death.

“I am dead inside,” she said.