These Public Defenders Want to Fight Bias From the Bench

But their push to unseat judges is drawing backlash from a surprising source—fellow Democrats.

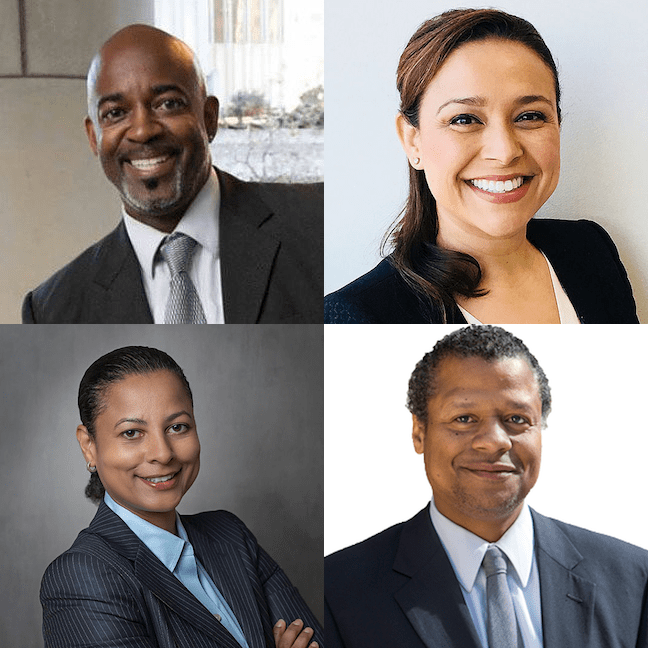

In early February, four longtime public defenders in San Francisco announced their plans to run for Superior Court judge, a position that would allow them to preside over the very same courtrooms where they had been defending indigent clients for years. The public defenders were targeting the seats of four judges who had been appointed by Republican governors, Pete Wilson and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the type of judges who rarely face serious challenges from either party. But instead of being greeted by local Democratic politicians with enthusiasm and encouragement, the public defenders were instead criticized for daring to run.

A week after the announcement, Assemblymember David Chiu, a Democrat from San Francisco, expressed a deep concern about the “politicization of the bench” speaking out with three local Democrats who defended the current judges (who have also described themselves as Democrats).

The blowback took some of the candidates by surprise. “I’m naive, man,” Phoenix Streets, one of the four candidates, told The Appeal. “When I started running, I thought we were going to have a conversation about the criminal justice system. … I did not realize that we were declaring war. But I’m glad we did, because that makes it much more fun.”

The four new candidates, all of whom are either Black or Latinx, hope to address the disproportionate impact of the criminal justice system on people of color in San Francisco, a famously “progressive” city. In 2016, the Department of Justice issued a 400-plus page report describing implicit bias against minorities in the San Francisco Police Department. According to a 2015 study, Black adults in San Francisco were more than seven times more likely than white adults to be arrested.

“The numbers don’t lie,” said Niki Solis, one of the public defenders running for judge. “There are numbers that show implicit bias and you need to address them. We think that San Franciscans would be well-served to go to the poll and elect critical judges. … We need to hold these [four] judges accountable and we need to say to the electorate that these numbers are stark, and they’re troubling.”

Solis, a formerly undocumented immigrant whose family arrived from Belize was she was an infant, explained that the public defenders are trying to transform the justice system wholesale. For starters, they’re focusing on diversion for those arrested and treating incarceration as an option of last resort. She believes new judges who better reflect the population they are serving could remake the justice system in a way that would minimize the worst aspects of biased policing.

California’s power brokers have traditionally refused to run challengers against whoever is appointed by the governor, because they fear an influx of money into normally staid judicial elections and they say judges are meant to be above partisan politics. But those aren’t the only reasons. Often, Solis explained, these appointments are drawn from law firms that have showered sitting judges with campaign donations and parties celebrating them. If no one runs against an appointee when the position is up for election, the judge’s name doesn’t even show up on the ballot. This lets one of the most crucial pieces of the criminal justice system, Solis argues, stay completely out of reach for anyone who isn’t politically connected.

The challengers chose these particular judges solely because they were Republican appointees and up for re-election this year, not because they were any more or less progressive than other members of the judiciary. But, as candidate Maria Evangelista recently argued in a blog post, new judges are needed to disrupt the status quo.

“Judicial elections are mandated by the California Constitution every six years to ensure there are checks and balances on judges who were given political appointments,” she wrote. “True judicial independence will come from electing judges from diverse backgrounds to eliminate implicit bias.”

Chiu disagrees that the sitting judges, two of whom are Asian, don’t represent the diversity of San Francisco. And while he doesn’t believe that incumbent judges are sacrosanct (he says he has supported challengers in the past), he thinks judges should be evaluated based on their records, not on who appointed them.

“The four judges that were selected to be opposed are all incredibly well-respected and well-qualified with long records of progressive achievements. The suggestion that simply because of who had appointed them, they were somehow less qualified to serve on the bench, I just didn’t agree with,” Chiu said in an interview.

Yet, across the country, public defenders are increasingly competing for seats in places where incumbent judges are unaccustomed to being challenged. They’re running with an eye toward transforming the criminal justice system from the most important position in the court, one that decides what evidence can be admitted, what charges can be levied, or whether a sentence truly fits the crime.

Kathryn Maloney Vahey, an assistant public defender who ran for a vacant position on the Cook County Circuit Court in Illinois last winter, explained that the county’s convoluted process for forcing a judicial election makes it so that “99.9 percent” of judges are retained. When vacancies do come up, they’re competitive affairs, and ones in which, she says, public defenders have traditionally not fared well due to their supposedly “soft” approach to punishment.

As progressive prosecutors have swept to power in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Houston, judges (who are often former prosecutors) have acted as barriers to reform. In Philadelphia, for instance, judges have so far thwarted many of District Attorney Larry Krasner’s attempts to reduce sentences for people who were given automatic life without parole as juveniles. In Cook County, Illinois, a judge got into a shouting match with a prosecutor who said the court should have offered bond to a woman who was seven months pregnant. She eventually had to give birth while being held for a probation violation. In Harris County, Texas, several judges named in a federal lawsuit continue to fight a district court ruling declaring the county’s bail system unconstitutional. The Harris County prosecutor, Kim Ogg, supports the ruling and reforming cash bail.

For former Harris County public defender Franklin Bynum, a candidate for criminal court judge, decisions like the ones made by the judges appealing the ruling are what pushed him to run. “This system is an indefensible system. Even a lot of the local politicians who are not seen as fire-throwing radicals say this,” Bynum told The Appeal. “I’m one of a chorus of people saying the criminal justice system in Harris County is fundamentally broken and it’s run by the worst people in the county. It has to stop.”

And, in his case, change is likely. In March, Bynum won his district’s primary unopposed. His opponent in the general election easily defeated the incumbent Republican judge and has support from religious conservatives, but is considered unlikely to win. Bynum, it should be noted, is running as a Democratic Socialist, something he said the local Democratic Party has urged him to tamp down his rhetoric about.

In Cook County, which leans overwhelmingly Democrat, Vahey won her primary against the incumbent, even without the endorsement of the local Democratic Party (which endorsed the incumbent). Vahey ran alongside a slew of other public defenders, many of whom were victorious—representing something of a public defender wave in Cook County. According to Injustice Watch, “Current or former public defenders won seats in 14 of the 23 contested races they ran in,” while just two years ago, “only six current or former public defenders ran in contested races, and only one of them won.”

The candidates aren’t confined to only urban areas that have seen recent progress on criminal justice reforms. Suzanne Hayden is a public defender in Clallam County, Washington, right at the tip of the Olympic Peninsula. She’s running for a district court seat that is being vacated by Rick Porter, a judge who instituted a “pay-or-appear program” in the courts, where defendants had to pay fines, do community service, or be incarcerated, which critics say improperly punished people who were unable to pay. The state recently passed legislation outlawing such practices. “I thought I would live and die as a public defender,” Hayden said, explaining that she hadn’t really considered running for judge before Porter left his seat and set the stage for a November election.

Even though recent successes point toward something of a trend, the fact that states have different rules or gatekeepers for how judges are elected or appointed remains a significant hurdle for many public defenders looking to get on the bench.

Todd Oppenheim, a public defender in Baltimore, experienced those challenges firsthand when he first ran for a circuit court judge seat in Baltimore in 2016, and then tried to get appointed to a judge position a year later. Neither bid worked. Judges often run together as a “slate,” Oppenheim says, pooling resources and making it extremely difficult for an insurgent candidate to make an impact in the polls. As in California, appointments to the bench in Maryland are often handed to lawyers at politically well-connected law firms, who go out of their way to make sure no one else can emerge as a viable candidate.

“The private attorneys … they go to every judge’s fundraiser, they get onto the committees on these bar associations, and one of them pulled me aside,” Oppenheim said, “and he kind of warned me after I announced my candidacy but had not filed with the state: ‘This is going to ruin your career. What are you doing?’”

The public defenders running in San Francisco are now not only up against their own party but also garnering stern editorials in the area’s major newspapers, one of which called their candidacies an “assault on an independent judiciary.” For these lawyers, the June 5 primary election represents a referendum on whether a criminal justice system run for and by the people can actually look like the “people,” instead of the well-connected few.

“As public defenders, we see [the justice system] day in and day out, and we have a unique perspective of what works and what people want done. How to treat people and how to speak to them, and speak to their issues so that they can get out of the criminal justice system,” Solis, one of the San Francisco candidates, said. “Now, more than ever, we need folks like us to stand up and be members of the judiciary.”