Protesters Say Hamilton County Sheriff Held Them Overnight Without Food, Water, Bathrooms

Two people, arrested and detained in Cincinnati after protesting the police killing of George Floyd, recall being held at the jail, outside, for hours.

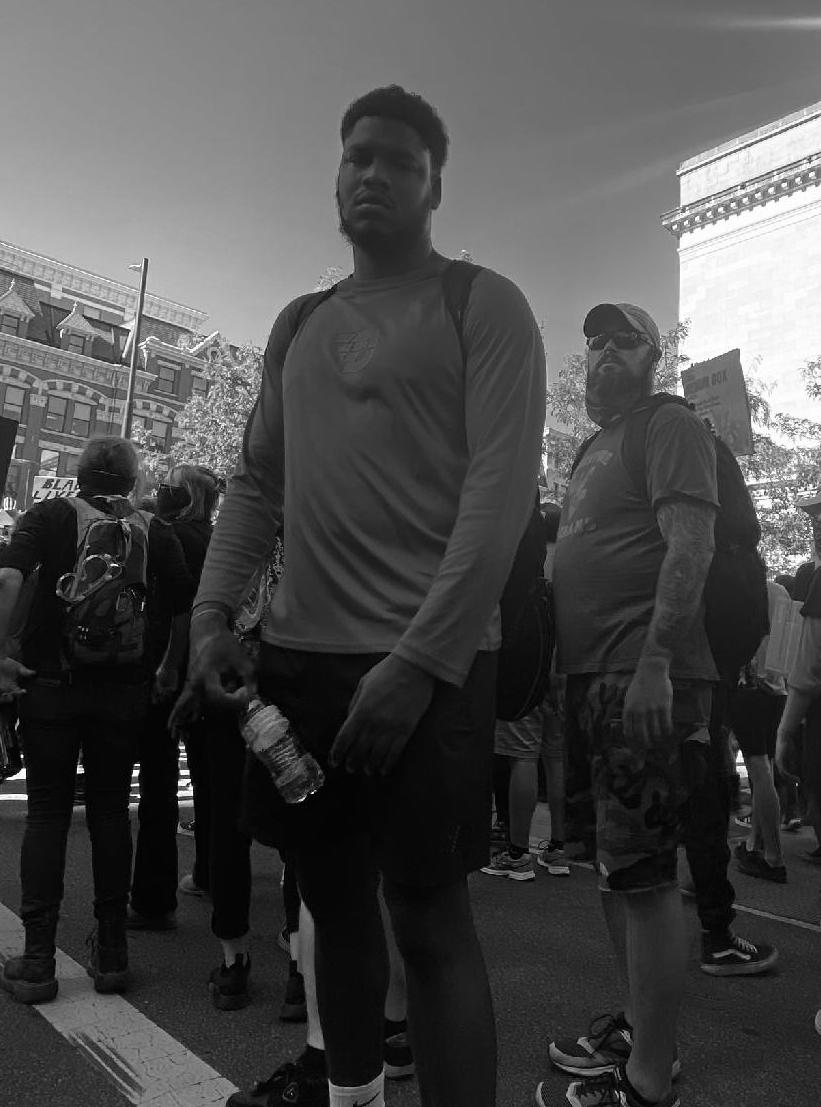

Tyson Wells, 22, wanted to participate in the peaceful protests taking place near his home in Cincinnati. So on May 31, he and a group of friends drove downtown to join the demonstrations meant to honor George Floyd, a Black man killed by a white former Minneapolis police officer in late May, and demand racial justice.

Wells had planned on abiding by the 9 p.m. curfew that Mayor John Cranley instituted. Instead, Wells was among the 307 protesters who were arrested by Cincinnati police and brought to the Hamilton County Justice Center. Wells and others say they were kept there, outside, in the jail’s sally port, from late in the evening through the early afternoon. Those held there allege they were denied basic rights like access to restrooms, water, and food.

According to Wells, as the curfew neared, he and his companions decided to head home. They were walking to a friend’s car when police tear-gassed them, Wells said. He and his friends ran but were eventually cornered.

“We all willingly got on our knees, put our hands up, and said, ‘we just want to go home,’” Wells told The Appeal in a phone interview. At first, according to Wells, law enforcement officers told him that he would be able to leave. But after a brief discussion with other officers, things went south.

“They didn’t tell us anything and just started handcuffing people,” said Wells.

Cincinnati police placed Wells on a Metro bus with other detained protestors. He was given no explanation about where he was going, and the bus idled for an hour. “They refused to let people use the bathroom, so people were literally pissing on everybody. Like I was standing in a puddle of piss,” Wells said.

Eventually, the bus took them to the Justice Center. Wells and the other bus passengers who had been detained were then brought into the lobby. The sheriff’s department told them they would be processed—fingerprinted, identified, and given citations—within a few hours and then permitted to leave.

When he was brought to the sally port through garage doors, Wells said he could see people jammed together, screaming for help. “People were laying on the ground, trying to stand up, but [law enforcement officers] wouldn’t let them stand up,” Wells said. Most of the people held there overnight, including Wells, had their hands zip-tied behind their backs, he said.

At this point, it was around midnight, and the sheriff’s department was processing between two to five people an hour, Wells estimated. During this time, he said, people were not given access to food, water, or a restroom, and some were urinating on themselves and vomiting.

“It was super cold … The wind’s blowing, girls have on shorts, I have on basketball shorts and a T-shirt. They didn’t give us any blankets,” explained Wells.

Neither the sheriff’s department nor the Cincinnati police responded to questions about why law enforcement chose to use the sally port to hold detainees. According to a Hamilton County public defender, the sheriff’s department had used the sally port the previous night to hold a smaller number of arrested protesters.

Anna Cleveland, 21, another protester detained at the Justice Center that night, says that she witnessed people having seizures while she was held there. “I know for a fact that two people had seizures and one person passed out,” she said.

“This one girl had a seizure that was so bad, we thought she died, because after her seizure ended, she didn’t wake up,” said Wells. The sheriff’s department clarified on Twitter that this woman did not die from these medical complications.

Both Cleveland and Wells describe the law enforcement officers present as being apathetic to the situation.

“The cops didn’t do anything … we were all yelling and chanting ‘no food, no water, no blankets’ for hours. And the cops were just standing there, like, smirking at us,” said Cleveland. “The cops did not care. They had packs of water like the ones you can get from the grocery store. Huge, 16-count packs sitting right behind them unopened. And I say, ‘hey, can we get some water?’ and they just smirked and laughed or walked away or told us ‘no’ or to ‘shut the f*** up,’” said Wells.

After more than 10 hours in the sally port, the sheriff’s department began to speed up its processing, said Wells. Cleveland said she was let out at around 11:30 a.m. and Wells said he was released at 12:30 p.m. A few people who had been held posted videos, describing their experiences.

The sheriff’s department did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment on the conditions in which Wells and Cleveland say they were held. But spokesperson David Daugherty told WCPO Cincinnati that officers were following proper procedure but were overwhelmed by the amount of people brought in.

“You got to remember we’re dealing–during the booking procedure–we’re dealing with the coronavirus response plan,” he told WCPO.

Both Cincinnati Police Chief Eliot Isaac, whose department does not operate the Center, and Cranley, the mayor, have claimed that detainees were permitted to use the bathroom, given breakfast, and allowed to go inside.

Samantha Silverstein, a training coordinator who works for the Law Office of the Hamilton County Public Defender, was among those present at the Justice Center when the protesters were being released. The previous day, she had visited with another group of detained protestors.

“I was actually up in the cells, and I saw a gym that had people in these green sleds, like the toboggan that you would use as a kid,” Silverstein said. “When [the Justice Center] gets overcrowded, they give inmates sleds to sleep in. And they put a mattress in the sled, but [people who are detained] sleep on the floor of a gym.”

Silverstein also noted that, since 2019, several people detained at the Justice Center have died due to medical complications. In one such case, a 25-year-old homeless woman was found dead in her cell after she didn’t attend her withdrawal treatment.

The Justice Center was also the site of national controversy during the start of the protests. On May 31, as Cincinnati residents began participating in marches, the sheriff’s department raised the “Thin Blue Line” flag outside the Justice Center, supposedly to honor an officer whose helmet was struck by a bullet that morning. The flag was later taken down.

Jacqueline Greene, a civil rights attorney with Friedman and Gilbert in Cincinnati, believes the treatment of protestors at the Justice Center and raising of a flag associated with the Blue Lives Matter movement are connected. She sees these actions as part of a larger effort to intimidate people and keep them from protesting.

“These prosecutions are politically motivated. They’re aimed specifically to undermine the movement for Black Lives. The use of force and the use of the criminal legal system are meant to achieve those ends, to chill speech, to intimidate people out of expressing their views, and out of standing up against racist policing and brutality,” said Greene.

Silverstein agreed. “I think that it is clear that [the Hamilton County Sheriff’s] efforts were ‘let’s show them for standing up to us.’ And they accomplished that because the people we’ve talked to said, ‘I’m never going to go to a protest again because I don’t want to go through this again,’” she said.

Greene, Silverstein, and other attorneys are working with individuals detained at the Justice Center to defend themselves in court or pursue legal action against the county. Greene believes the way protesters were held at the Justice Center was illegal. “The conditions of confinement in the sally port were unconstitutional,” she said. Both Cleveland and Wells are considering taking legal action.

In 98 cities across the U.S., law enforcement has employed tear gas against protestors, and at least 20 people have suffered traumatic eye injuries from rubber bullets. In Washington, D.C. and New York City, protesters who were arrested said they were held in jail conditions similar to those Cleveland and Wells described—without food, water, or masks to protect them from COVID-19. Silverstein said that officers at the Justice Center made no effort to provide masks, and neither Wells nor Cleveland were provided any protection from possible infection.

In light of the protests that Wells and Cleveland attended, the national demand for police reform has trickled down into Ohio. The Columbus Freedom Coalition, a group of prison and police abolitionist organizations, have been organizing in their community and have called for a total defunding of the police. They propose allocating resources to underfunded neighborhoods in need of housing, healthcare, and investment. Ohio lawmakers like Representative Cindy Abrams, a former Cincinnati police officer, has introduced a 15-point bill that includes psychological tests for new recruits, training that prioritizes de-escalation, and a demand for diverse staffing.

To Wells, it felt as if Cincinnati law enforcement officers were trying to terrorize anyone who questioned their authority.

“They just stripped away your rights and what it felt like just living a normal life,” he said of law enforcement officers. “They just wanted to make it feel as worse as possible … They just wanted to just force power on everybody.”