Overdose In An Arizona Prison? Get Ready To Pay Up.

‘Worst policy imaginable’ punishes, rather than treats, patients who earn less than a dollar an hour, advocates say.

The Arizona Department of Corrections has a new policy that will charge prisoners if they are taken to the hospital for substance use.

The policy, enacted March 15, states: “Inmates that require transport to the hospital due to substance abuse shall be charged restitution for all medical related expenses and cost of staff overtime in accordance with Department Order #905, Inmate Trust Account/Money System.”

Even before this new policy, 10 percent of deposits to a patient’s account were being taken to pay off “medical treatment costs,” according to a Department of Corrections manual. The department was already charging prisoners the cost of positive urinalysis tests, as well as a $4 copay for healthcare visits. Prisoners in Arizona earn between 10 and 80 cents an hour, according to the Department of Corrections.

In a statement, Bill Lamoreaux, a public information officer for the Department of Corrections, said the policy was designed to hold prisoners accountable for their own actions. “ADC understands that the struggle with addiction is not an easy one,” he wrote. “However, obtaining, contraband illegal drugs while incarcerated requires a series of deliberate and extremely poor choices.”

But advocates condemned the policy as counterproductive, dangerous, and cruel because it treats substance use disorder as grounds for further punishment.

The solution is treatment, not punishment.

David Fathi American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project

“From a public health perspective, this is the worst policy imaginable,” said David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project. “The solution is treatment, not punishment. This policy is just reflexively punitive and entirely counterproductive.”

Seventy-eight percent of people entering Arizona prisons have “significant substance abuse histories,” according to the department’s report for March 2019. Methadone is available only to incarcerated women who are pregnant and addicted to opioids, according to the department.

Lamoreaux, the department spokesperson, told The Appeal that it offers a range of treatment options to roughly 3,000 prisoners each year (out of a total population of more than 42,000 prisoners), and that part of the problem has been finding qualified staff. “Substance abuse counselors are in short supply in Arizona and we have difficulty attracting these licensed individuals to work in a prison,” he wrote.

Karen Hellman, division director of Inmate Programs & Reentry for the Arizona Department of Corrections, made a similar point at the state House Judiciary Committee in March. “I could not today treat everyone in the system who needed treatment immediately,” she said. “The need of the inmates is greater than our capacity to deliver.”

When treatment is provided, it’s often inadequate, said Rebecca Fealk, program coordinator for the American Friends Service Committee in Arizona. She said people incarcerated in Arizona have told her group, “‘Oh yeah, my treatment was a worksheet that asked me about negative outcomes from using.’”

“We’re not asking the right question to say, Well, why are you using?” she said. “How can we address potentially the trauma or ongoing pain that you’re having?”

Zach Perrino was using heroin when he was sent to prison in Arizona in 2011. He and a friend stole less than $200 worth of items from a Dillard’s department store, which Perrino told The Appeal he then returned for cash to buy drugs. He was convicted of organized retail theft and sentenced to a total of six years—five for theft and one for a probation revocation, Perrino said. He was released on Jan. 3, 2017.

“My initial thought was my life is over,” recalled Perrino when he learned his sentence. “I’m going to end up dying in prison. I should just get comfortable here.”

How about you fix the problem and not just try to kick it on down the road to someone else?

Zach Perrino former prisoner in Arizona

He continued using heroin while incarcerated. Three years into his sentence, though, he became sober, he said, supported by the mentorship of a fellow prisoner. Other than Narcotics Anonymous, he didn’t recall any treatment services available to him. Charging prisoners for going to the hospital punishes them for their addiction, he said.

“How about you fix the problem and not just try to kick it on down the road to someone else, to someone’s family?” said Perrino, who earned about $20 every two weeks while he was incarcerated.

Healthcare for Arizona’s prisoners has been the subject of extensive litigation and advocacy from prisoners. In 2015, a settlement agreement was approved in the class action suit Parsons v. Ryan, filed against the Department of Corrections by the ACLU of Arizona, ACLU National Prison Project, Prison Law Office, and the Arizona Center for Disability Law.

However, last June, U.S. Magistrate Judge David Duncan fined the department about $1.4 million for failing to make several of the required improvements. In December, U.S. District Judge Roslyn Silver appointed an independent expert to evaluate healthcare services for Arizona prisoners.

“[The new policy] certainly is consistent with some of the resistance that we have seen in the Parsons case to providing even basic and life-saving healthcare,” said Fathi. “This obviously does affect the ability of our clients in Parsons to get necessary healthcare.”

Arizona’s policy runs counter to the reality of addiction, said Dr. Kimberly Sue, medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition and a physician at Rikers Island in New York City. Instead of viewing it as a medical condition, it is seen as a “moral failing,” she said. An opioid overdose inside a prison indicates “medical mismanagement” of a treatable disorder, she explained.

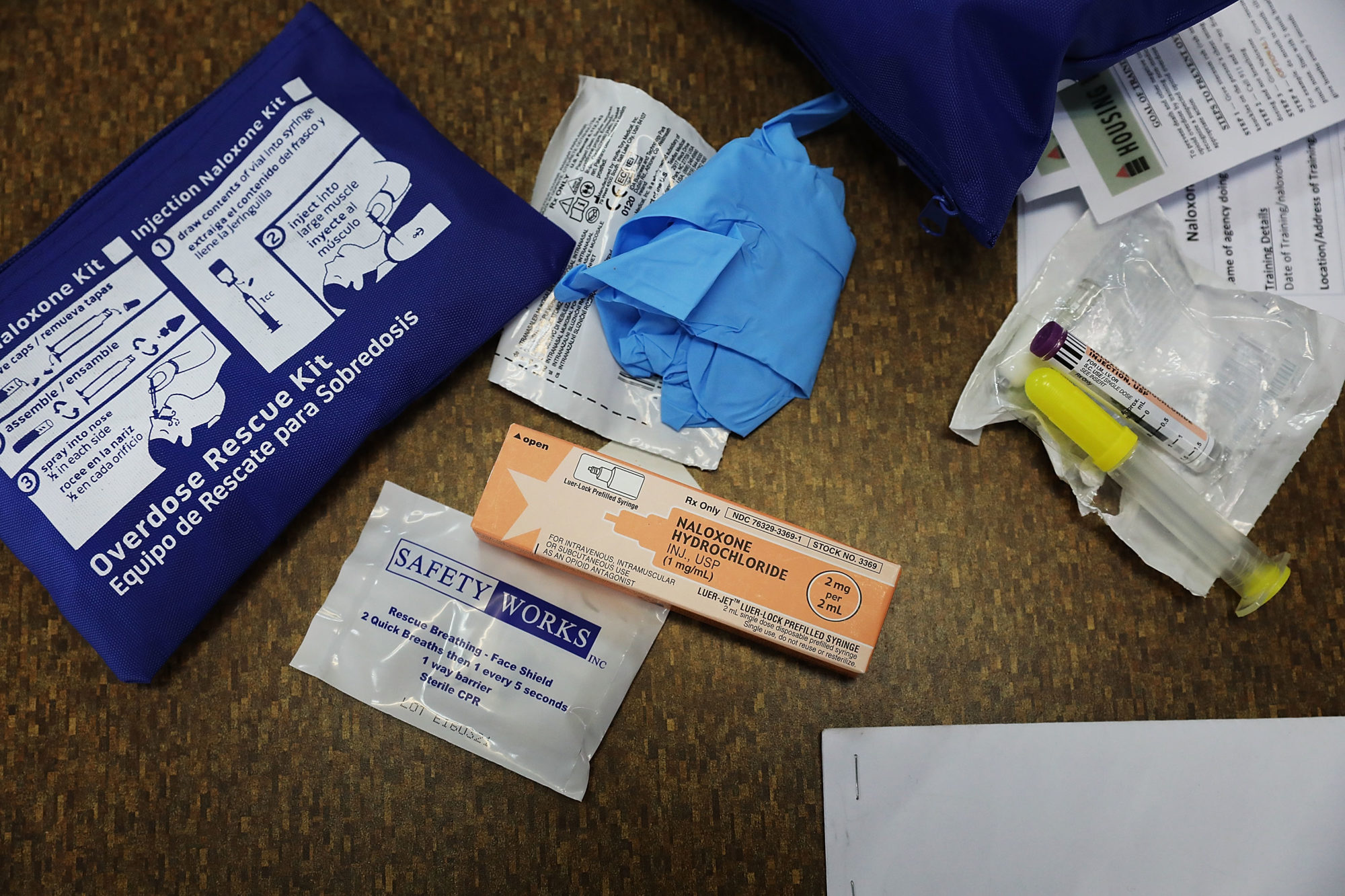

“For the people that are currently incarcerated, we should be providing medications if at all possible in the case of opioid use disorder,” she said, noting that there are three Food and Drug Administration-approved medications. Rikers offers medication-assisted treatment to eligible detainees.

People don’t decide, ‘Hey, I think I’ll overdose today.’

Dr. Josiah Rich The Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights at The Miriam Hospital

Dr. Josiah Rich, director of The Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights at The Miriam Hospital, agrees that Arizona’s policy betrays “an ignorance about what the disease is and how to treat it.”

“People don’t decide, ‘Hey, I think I’ll overdose today,’” he said. “They don’t decide, ‘Oh, I better not overdose today because I might have to pay money from my account to pay for the treatment I’m going to need.’ People overdose because there’s a discrepancy between how much tolerance they have and the amount and purity of the drug and the potency of the drug that they consume.”

Incarcerated people, particularly those with underlying mental health or substance use issues, will often self-medicate because of the misery of prison, said Sue.

“The conditions of confinement are meant to be distressing,” she said. “They’re meant to be uncomfortable.”

Perrino agrees that living in prison, coupled with a lack of services, made getting sober while incarcerated “extremely difficult.” He stopped using heroin despite his incarceration, not because of it, he said.

“To get sober and to get the root of addiction, you have to be vulnerable,” he said. “That’s a place where you cannot be vulnerable.”