He Found Freedom After More Than Two Decades In Prison. But He Was Released Into A World Changed by COVID-19.

Euka Wadlington was denied clemency by the Department of Justice under Obama. But then he mounted a legal challenge to sentencing enhancements used in his drug case; in April, a federal judge granted his release. Now he’s adjusting to freedom—and life in the coronavirus era.

In 1999, Euka Wadlington was convicted in federal court in Iowa on two drug-related charges. The case was based largely on informant testimony and no drugs were found on Wadlington when he was arrested. No amount of drugs was alleged in the indictment and the jury made no drug amount findings. But at sentencing, the district court determined that Wadlington was subject to mandatory life imprisonment under the statute and the then-mandatory guidelines based on his prior convictions. Wadlington was then sentenced to two concurrent life sentences and 10 years’ supervised release. Here, Wadlington talks about his case, becoming a GED tutor in federal prison, having his hopes for clemency dashed during the Obama administration, and finally being freed in April amid the COVID-19 pandemic after serving 21 years in prison.

Before I was incarcerated, I was working in construction. I was kind of struggling, you know, but at the same time I was making enough money to pay the bills. A friend came by talking about “You need to help me.” Me being a so-called friend, I tried to help this guy, and all the time, he was a government informant trying to set me up.

I was in Chicago. The guy was from Iowa, and he just popped up on that particular day and said, “I’m here, at this hotel by the airport.” It was me and another girl, and she was supposed to be a distraction. I was gonna go get the money and drive off. She was gonna stay there as collateral until I came back. Once I left she was gonna ask him to take her to get her something to drink, go to the bathroom at the gas station and sneak away to meet me somewhere in the cab.

That was the plan. When I got up there, as soon as I opened the door, guys bust out the bathroom and the connecting room and started hollering “DEA!” A U.S. attorney in Iowa is the one that brought the charges. They have deputies in a task force who try to apprehend guys they believe were trying to sell drugs and bring drugs into their town.

They tried to set me up, but at the same time they found no drugs, no money, nothing. And apparently they knew I wasn’t gonna bring no drugs either, but the base of it all was just to get me there in that spot and try to make me start cooperating with the government. At the hotel, they was telling me right there on the spot “You gotta help yourself, if you don’t help yourself, you’re going to get a life sentence.” I declined.

So I ended up getting charged and going to jail. That’s where I started catching charges of conspiracy, attempt to deliver and then an actual charge of delivery—saying that two years prior to that arrest date, I had supposedly served an undercover informant some drugs. It was proven that I never even saw this guy before in my life when I went to trial. I lost on the other two counts, conspiracy and attempt to deliver, and I ended up going to federal prison.

The case wasn’t very strong, everybody admits that. But the way they played me inside the case—giving me two charges with a life sentence on each charge—was extraordinary. Because they’d say, “Well, you could get relief on this charge right here, but you still have life over here, so there’s no relief.”

The prison environment, it was harsh. I was in two United States penitentiaries, Leavenworth in Kansas and Terre Haute in Indiana. Then when my security level dropped, I ended up going to Greenville Federal Correction Institute in Illinois.

In all three places I was a GED tutor. How it started was, my first cellie didn’t know how to read and write at all. He was an older cat, and he never read his mail inside the cell. And then I found out that he was taking his mail to someone else to read and write the letters to send back to his wife. The dude who was doing it for him used to come behind his back and tell me negative stuff about him, how he was stupid and all of that.

I told him that’s not cool. You helping the dude is one thing, but talking behind his back—why don’t you just teach him? He said, “Forget him, he paid me to do it.”

I went back to the cell and I had to figure out a way to bring it to him, because to talk to someone about their ignorance in there can be damaging to you. They hold that close. They don’t realize they’re just not academically astute. They were smart; it’s just not book stuff. I never said “You’re dumb, you’re stupid” to any students because I know how that feels, to hear you’re dumb, you’re nothing.

I had to find a way to show them. That came through a position of letting them know, hey, at the end of the day it don’t matter how dumb and how smart you are, we are both in the same position. All we have is to help each other. Not everybody in federal prison has a life sentence. I was unfortunate because I had two. That helped me in a way to get those guys to listen; I’m not talking from I’m a year or two from the door. I had to fight my way out.

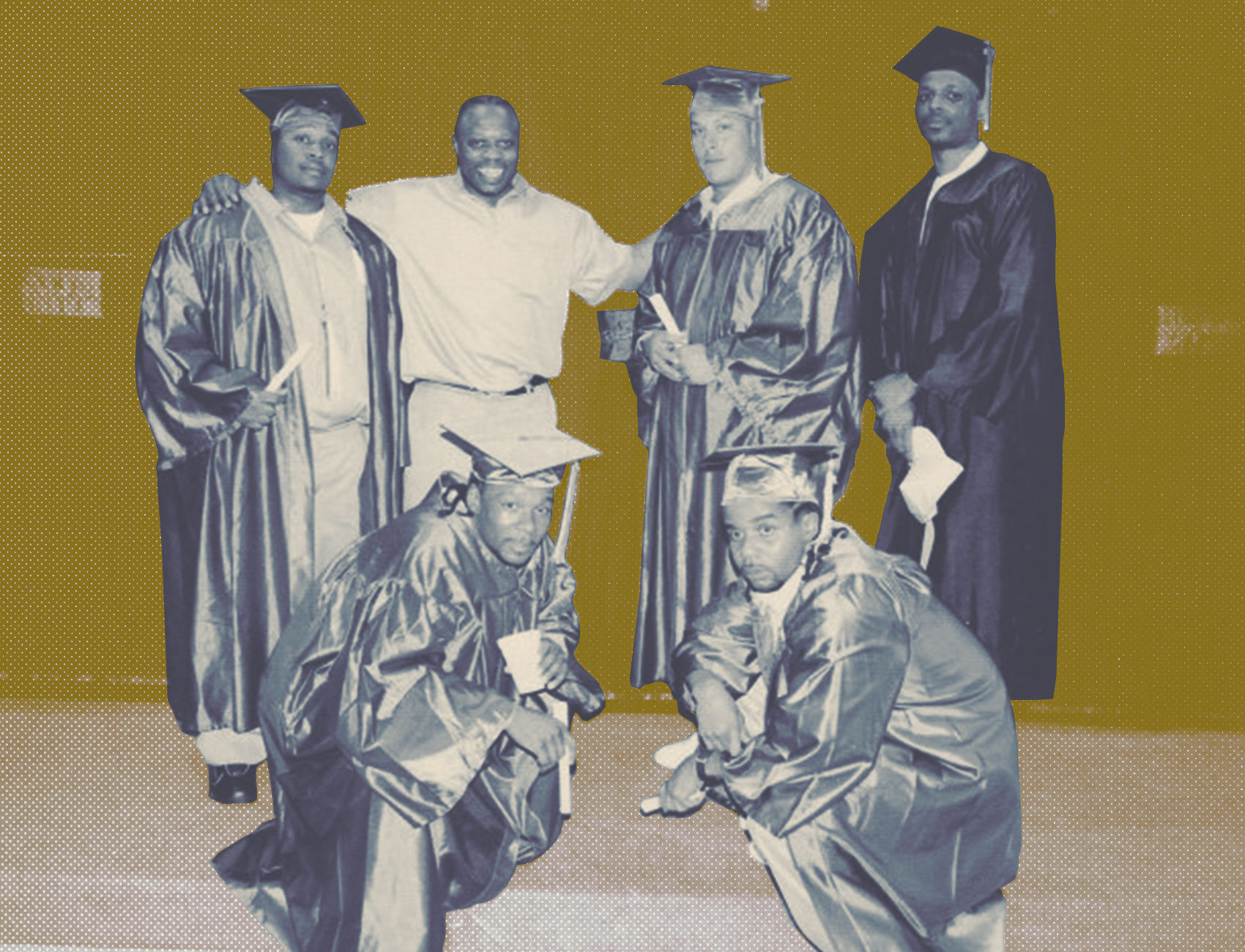

I had figured out a way to reach these guys to get them inside the classroom to get their GEDs. It was a struggle at first, but then I got comfortable in helping people. So that became my niche everywhere I went, from Leavenworth to Terre Haute to Greenville. In those places, I ran across a lot of good guys, fighting their cases. And I helped a lot of them obtain their GEDs.

In a prison setting, it’s not an age range that you teach, it’s all mixed—you teach anybody from 20 to 100. And I had older guys come in there and actually obtain their GEDs. As for how many, I can’t count them all. We might have 30 people in the classroom, and out of that 30 people you might get five or six who pass the GED test. Not all of them will pass it, but every time they see someone get a GED it inspires them a little more to try a little harder. Then some of the students that were pretty good, I tutored them and then they became tutors. Then they start rotating into their own classrooms. Then some of the people they taught, they teach them to become tutors—so it was a pyramid effect. It was good in all senses of it.

In Greenville what was so remarkable was that I was hooking up with colleges to come into the prison and help those guys get their GEDs. They came in to play sports with us, they played chess with us, and they taught in the classroom. College professors and students, too. It was a pretty good thing. I kind of liked it there; it was just a joy in helping others.

Under the Obama administration, I submitted my petition for clemency. I just knew for sure that was going to be a home run for me. I knew I had never had a disciplinary report; I did nothing but help other guys obtain their GEDs and became a mentor for the prison.

When I submitted my petition, I had a lot of support behind me. But for whatever reason, it was told to me that the prosecutor rejected it. He was saying some things about me—I don’t know what it was—and I ended up getting denied. And on the same day my clemency was denied, Jan. 6, 2017, my mother passed. So it was like a double blow for me.

When I heard my clemency application was denied, I didn’t go back to my cell. I went back to the classroom. The students were waiting to see what the answer was for me. And this is what I told them. I said, “This is why I fight every day, so you won’t have to feel this pain that I feel right now. You still have a chance to go out there and make something of yourself. Getting your GED is a first step in telling yourself hey, you can do better because you want better. And nobody can tell you anything different. But at the same time, I gotta take this and I gotta strive. This isn’t where I give up. This is what makes me stronger. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be, y’all might have to carry me up out of here, but I’m going to do whatever I can, you know what I mean?”

It was a lot of tears in that classroom. But at the same time, it wasn’t what they were asking me or saying to me, I knew it was them watching me. And that’s how they collected a lot of strength, because they saw how I carried myself despite all obstacles and all of the pressure and all of the things that I was trying.

Right after I got denied for my clemency, my friend Richard, who was also incarcerated at Greenville, said, “You oughta read this Mathis case, it might apply to your situation.” He was like—a jailhouse lawyer, is what we called him. He talked to certain people that were trying to fight their cases.

I took two weeks going through the case thoroughly and I thought, yeah, it did apply to me. So I filed a petition in 2017 to the district court in East St. Louis in which the judge found that I had merit in my claim. I found that all the stuff that they had put in concerning my prior convictions was incorrect, so they had me doing time for inaccurate information.

Apparently the state had charged me for delivery, but the judge had ruled it was nothing but simple possession. The difference is, with a delivery charge your sentence can be enhanced for it. So they took both my possession charges and claimed them to be delivery charges.

At the end of the day, the judge ruled that what I said was correct. She found that the state’s statute was overbroad and they can’t use those prior convictions against me to enhance my sentence.

So without the prior convictions, the maximum sentence I had was 20 years.

I was released on April 7—in the midst of the coronavirus. It was definitely weird; I’m actually enjoying this weirdness though. Because I don’t have to rush outside to make things happen. I get a chance to see what’s going on on the outside before I venture out into society.

As sad as it sounds, it’s beautiful for me. I don’t like to see all this death that’s going around, but people got this pandemic mixed up. They’re thinking that they don’t want to stay at home and all this stuff. I stayed in prison for 21 years—staying at home for a month, even six months should be nothing for them as long as they can provide for themselves.

I would rather do that and live than catch the coronavirus and die. That’s the choice, would you rather live or die?

In prison, before I was released, we went on lockdown. I was actually on lockdown when they came and got me. They were telling us, “This is a pandemic, this is something that’s going on and we’re not having any reported cases here. So this is what we’re going to have to do, we’re going to have to take the necessary precautions.”

It can come in there through staff, transferred inmate, contractor, there are numerous ways it can come in there. And they are still on lockdown, from what I understand. Lockdown sucks, I’m gonna tell you that right now. It ain’t no secret about it—nobody likes to be stuck in a prison inside of a prison. It’s a lot of irritation. You got some who cry about it and whine about it and some just sit back and enjoy life—and I’m the latter, I just sit back and try to work my way through it.

But it’s over, forever. I’m not going back. I’m not trying to do nothing to get myself in trouble.

I’m living with my uncle, and I got a little brother and aunts and cousins. And I got my six children. I have eight grandkids—I’m a grandpappy. They love their grandpa; I love my children and they love me too, so that’s a beautiful thing.

I came home open-armed, and everybody tried to help me. You know, listen, I’m supposed to be this hardcore criminal but I had tears in my eyes. I missed my daughter’s first heartbreaks, I missed my son’s basketball games and graduations and being there for my daughters when they were having their children. I missed that.

But I didn’t miss one of them getting married, I’m gonna be there for that. So it ain’t all about just what I missed, I gotta think about the things I still have a chance to do.

As told to Roxanna Asgarian