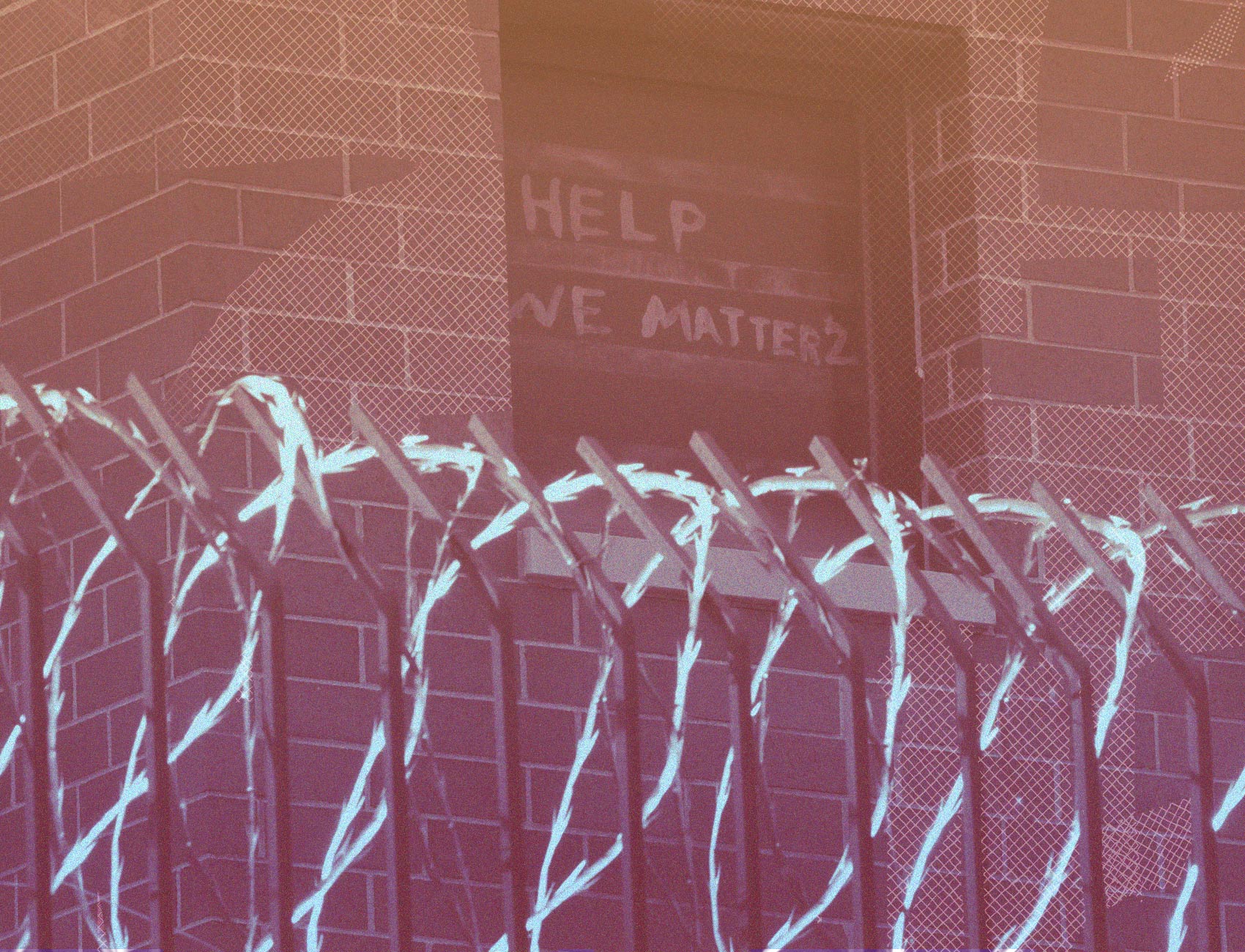

Pretrial Detention During A Pandemic Could Be A Death Sentence. Yet, Prosecutors Continue To Use It To Extract Plea Deals.

A deadly pandemic should not be used as a bargaining chip against poor, detained people charged with crimes.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

Jury trials have almost completely ceased in Texas since March and, with very limited exceptions, the Texas Supreme Court has barred courts from conducting jury trials until September 1. That means that, at least until then, the more than 36,000 people across Texas who are detained in local jails while awaiting their trials have almost no chance of testing the allegations against them before a jury of their peers. Virtually none of these people can afford to post the cash bond required for their release; their only hope of getting out of jail in the midst of a deadly pandemic is to take a plea deal and be sentenced to time-served or a short term in jail.

Judges and prosecutors are surely aware that people accused of crimes cannot exercise their right to a jury trial at the moment, but they continue to “move” cases through plea deals. Texas prosecutors have “expedited plea negotiations” and even “oppos[ed] all pre-trial release to pressure defendants to accept plea bargains.” Judges regularly conduct plea dockets via Zoom. Since April 1, people in Texas have pled guilty or no contest in more than 20,000 cases. And so, despite the constitutional right to a jury trial effectively suspended, the machinery of “justice” continues to churn.

Plea bargaining has been traditionally understood as a negotiation between the prosecution and the defense “in the shadow of trial,” meaning the person charged weighs the risks of going to trial with the plea offer and then decides whether to take the plea. But in reality a different factor weighs heavily for a person who is detained pretrial and cannot afford to pay for their release: whether they will be released from jail if they accept the plea deal.

In even the best of times, pretrial detention is used coercively to extract pleas from people who are in jail only because they cannot afford bail. It has a devastating impact on the people detained, as well as their families: research has shown that people detained pretrial are more likely to be convicted, more likely to be sentenced to jail, less likely to be sentenced to probation, and are given longer sentences than similarly situated people who are not detained. These consequences have cascading harmful effects, impacting a person’s ability to obtain and keep a job and housing, their lifetime earnings, and even whether they can see their children. Pretrial detention also causes innocent people to plead guilty just to get out of jail.

Now, the “shadow of trial” has all but disappeared, and a deadly pandemic is running rampant in detention facilities. Tens of thousands of people incarcerated in Texas jails and prisons have tested positive for COVID-19, over 16,000 of them in Texas prisons alone. More than one hundred incarcerated people have died. Pretrial detention under these conditions could be a death sentence, but prosecutors continue to use it to extract pleas, with judges signing off on these deals every day. And the growing backlogs from these cases—many of which will ultimately be dismissed—further overcrowd Texas jails, causing more viral spread, serious illness and death.

One simple approach could help mitigate this crisis: any time a prosecutor offers a plea deal of time-served or less than a year in jail, the person charged should also be offered release on personal bond, meaning that they promise to return to court without having to pay for their release. By the same token, defense attorneys should file motions for release on personal bond and use plea offers of time-served or a short confinement in jail as evidence that the prosecutor does not believe that the person charged is a threat to public safety. After all, if the prosecutor believes the person can be safely released from jail—which we can presume if they offered time-served or a short jail term—they should also agree to release on personal bond so the person can return to their family and community to see the day when they can face the allegations in a trial.

This is a crisis that has shown no indication of waning. A deadly pandemic should not be used as a bargaining chip against poor, detained people charged with crimes.

Amanda Woog is Executive Director at Texas Fair Defense Project.