Pressley, Tlaib Announce Bill to Limit Criminal Background Checks on Renters

Formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to become homeless than people without criminal backgrounds. The Housing FIRST Act would ban credit-check companies from including criminal history information on prospective tenants’ files if enacted.

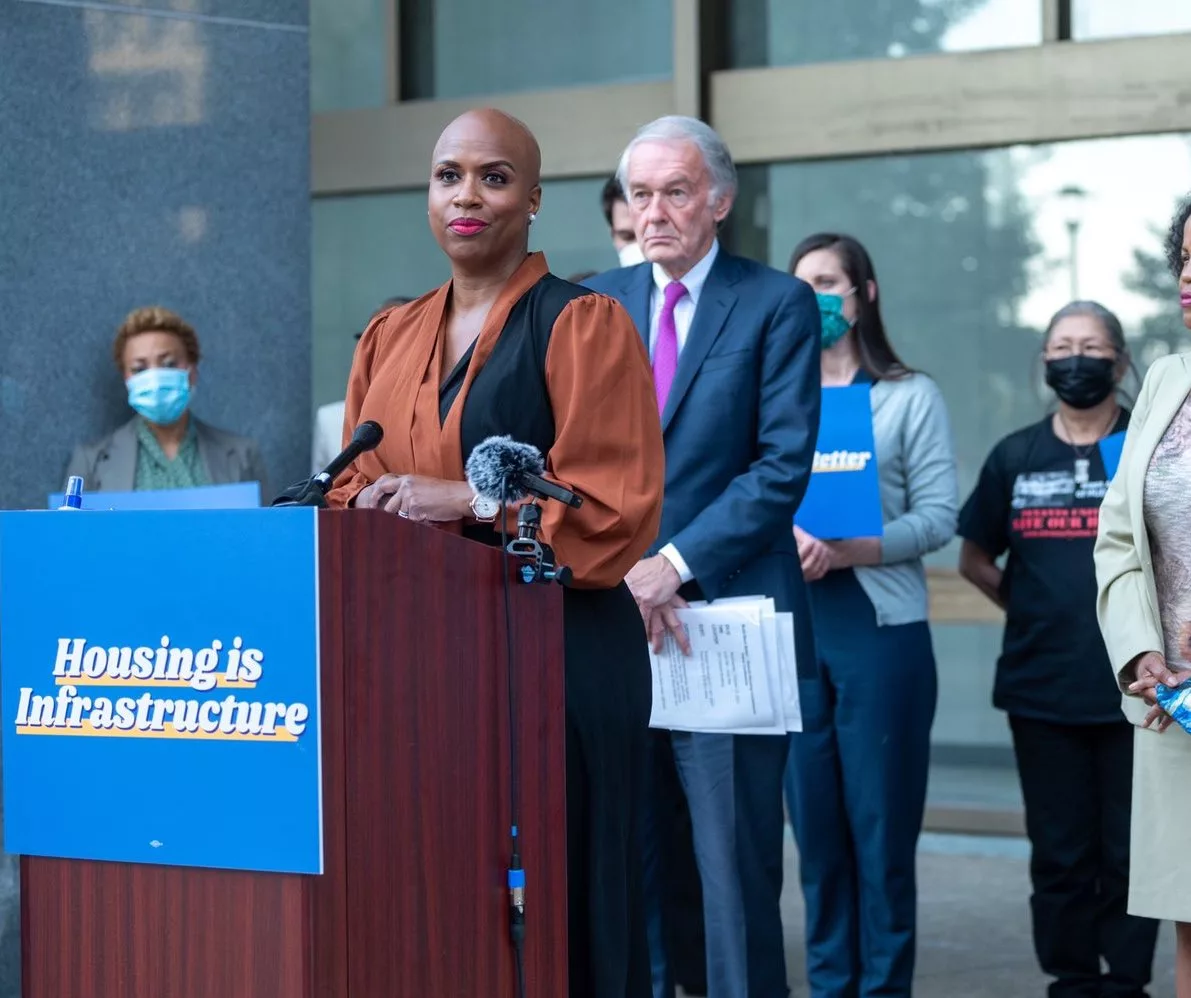

U.S. Representatives Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib will introduce federal legislation today that limits landlords’ abilities to use criminal background checks when screening potential tenants.

“Safe, stable and affordable housing is a fundamental human right, including for the millions of people with a record,” Pressley, whose father and husband both served time in prison, said in a prepared statement. “It’s time we remove the systemic obstacles that have exacerbated the prison-to-homelessness pipeline, perpetuated the cycle of mass incarceration, and denied housing to people who need it. Our bill does just that and will move us closer to true housing justice in America.”

Most landlords—approximately 90 percent, according to the National Consumer Law Center—use third-party companies, sometimes known as credit reporting agencies, to run background checks on current or prospective tenants. Under current law, a landlord may use those reports to deny the person housing, refuse to renew a lease, or place more onerous conditions on the tenant, such as requiring a co-signer or a larger deposit.

The bill, called the Housing for Formerly Incarcerated Reentry and Stable Tenancy (Housing FIRST) Act, amends the Fair Credit Reporting Act by expanding restrictions on what information can be included in background checks on prospective tenants. Under current law, background checks cannot list arrests older than seven years—but there is no expiration date for convictions.

A draft version of the Housing FIRST Act shared with The Appeal forbids consumer reporting agencies from including any arrest that did not result in a conviction, as well as convictions of children, people who have completed their sentences, or people on probation or parole. The bill would also ban agencies from including information related to expunged or sealed sentences, noncriminal citations, and court fees or other related payments.

“From Detroit to Boston, every human being deserves access to safe, affordable housing, including people who were formerly incarcerated,” Tlaib said in a press statement. “We must prioritize restorative justice, lead with compassion, and recognize the human dignity of our neighbors as we work to dismantle the cycles of mass incarceration and housing discrimination.”

Tenant screening reports often include inaccurate information, according to a report by the National Consumer Law Center, a nonprofit that focuses on consumer protections. That group and several other organizations—including Justice 4 Housing, Prison Policy Initiative, and The Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls—support the bill, according to a press release from Pressley’s office.

These potentially devastating errors have led to numerous lawsuits against background check companies. In one notable case, the Federal Trade Commission filed a complaint against a Texas firm called RealPage, Inc., alleging that, during at least five years, the company reported that potential renters had criminal convictions that they didn’t have. In 2018, the company agreed to pay $3 million in civil penalties, which, at the time, was the largest settlement the FTC had obtained against a background check company.

But a few million dollars is a proverbial drop in the bucket for the multi-billion-dollar industry. In 2021, when private equity firm Thoma Bravo bought RealPage, the latter company was valued at approximately $10.2 billion.

Errors in background checks are just one piece of the story. For the millions of people with criminal convictions, accurate background reports can still make it hard to obtain housing. According to a 2018 report from the Prison Policy Initiative, formerly incarcerated people were almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than those who have not gone to prison. Formerly incarcerated Black men and women were particularly at risk of becoming homeless.

Few protections are in place to protect formerly incarcerated people from housing discrimination even though housing stability helps reduce recidivism, said Ron Pierce, Policy Analyst for the Democracy and Justice Program at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, a nonprofit advocacy group. Removing obstacles to housing should not be “such a hard sell,” he said.

Pierce was incarcerated in New Jersey for thirty years. Pierce told The Appeal that, about six months after he returned from prison in 2016, he moved into his fiance’s trailer. Even though Pierce’s partner had received permission for him to move in, the couple received a notice on Christmas Eve that ordered them to leave or eviction proceedings would begin. Although they attempted to fight it in court, Pierce eventually moved out.

“They made it really hard for her,” said Pierce. “Just coming home, the last thing I want to do is make life hard for somebody that’s trying to make life easier for me.”

He secured free housing for two years by staying at a family member’s home, he said, which allowed him to get back on his feet.

“That’s why I was able to graduate college and get stuff together,” he said. “Now I own my own house so now nobody can tell me I can’t live there.”

Disclosure: Elizabeth Weill-Greenberg previously worked with Ron Pierce at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice.