Political Report

Virginia Ends Prison Gerrymandering, the Latest Chapter in a Recent Tidal Wave

New law changes where incarcerated people are counted for redistricting. Advocates vow to push against felony disenfranchisement next year.

A new reform changes where incarcerated people are counted for redistricting. State advocates vow to push against felony disenfranchisement next year.

Virginia is the latest state to end prison gerrymandering, which is the practice of counting incarcerated people where they are detained rather than at their last known residence for purposes of redistricting.

The adoption of Senate Bill 717 and House Bill 1255 this week paves the way for Virginia to draw fairer maps. The identical bills, which also make other changes to redistricting criteria, were passed by the Democratic legislature in February. Democratic Governor Ralph Northam approved them last week under the condition that lawmakers adopt a technical change, which they did on Wednesday.

Virginia adds to a tidal wave of state action against prison gerrymandering that seemed unthinkable just a year ago.

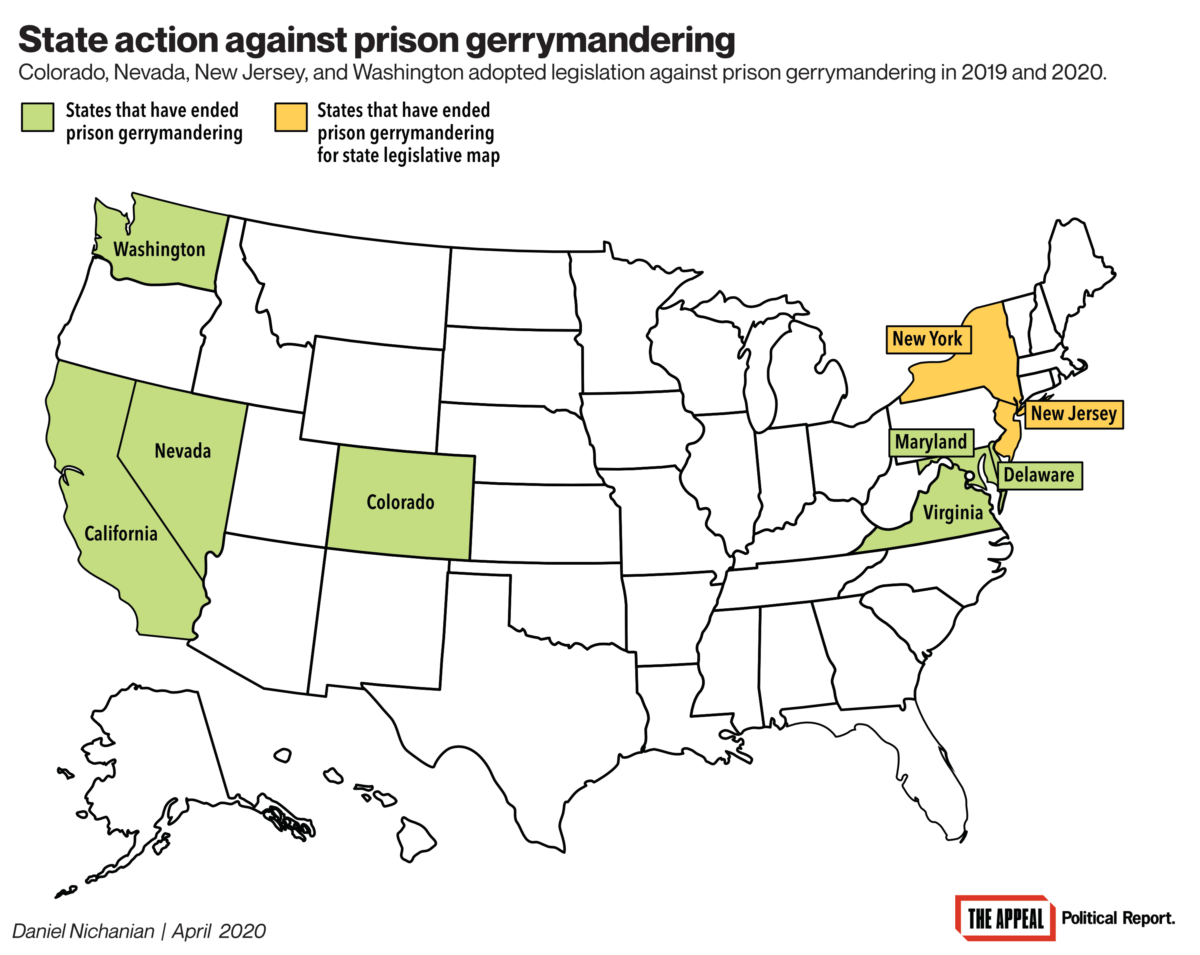

Since May 2019 alone, five states—Colorado, New Jersey, Nevada, Washington State, and now Virginia—have adopted laws against prison gerrymandering. Until then, only four had done so—California, Delaware, Maryland, and New York—and all years earlier.

When they next draw their legislative maps, and in most cases their congressional and local maps as well, these states will count people where they last lived.

“The reality is that when they’re released from prison and they’re back in their home locality, that’s where they need resources,” said Tram Nguyen, co-executive director of New Virginia Majority, a progressive group that supported Virginia’s laws. “It’s their home safety nets that will be important, and so it’s important that they be counted in their home localities.”

When New Jersey adopted a similar reform in January, Aaron Greene, associate counsel at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, told me that as long as states maintain prison gerrymandering, “the system is set up to take citizens out of their communities… and increase the political power of [other] communities. They are just bodies counted. Legislators don’t consider them citizens but they play a role in their political power.”

Prison gerrymandering shifts political power toward the typically more rural and whiter communities where prisons are located, and away from cities and areas with more Black residents that suffer the brunt of overpolicing and incarceration.

Besides skewing statewide maps, it can gravely distort the boundaries of local districts, such as those of city councils and county commissions, based on where a jail or a prison is located. According to the League of Women Voters of Virginia, seven Virginia counties drew a district this decade where at least 25 percent of the population is incarcerated; in Lunenburg County, there is a district where two-thirds of a population is incarcerated.

In Virginia, the incarceration rate among African Americans is five times higher than among whites, and consequent political inequalities have been a longtime source of concern.

“When we’re talking about the voting bloc and voting power, African American votes get watered down when people who cannot vote are included in the vote totals,” Democratic Delegate Marcia Price told the Virginia Mercury in February. Virginians in prison over a felony conviction are indeed barred from voting, on top of getting counted in a way that amplifies the representation of areas they are not from.

The new laws do not change this prohibition on voting.

In fact, Virginia’s felony disenfranchisement rules are exceptionally harsh: Anyone convicted of a felony loses the right to vote for life. Since 2016, though, the state’s governors have systematically restored people’s voting rights via executive action upon completion of their sentence — including terms of prison, probation and parole. Terry McAuliffe began that policy in 2016, and Northam followed it.

Democrats’ legislative takeover in November 2019 opened the door for Virginia to further expand voting eligibility.

In December, Democratic Senator Mamie Locke filed a constitutional amendment to abolish felony disenfranchisement and guarantee the right to vote to any voting-age citizen. In practice, SJ 8 would enfranchise people on parole and probation, as 18 states already do, as well as incarcerated people, as is the case in Maine and Vermont.

Organizations that champion voting rights, such as the ACLU of Virginia and New Virginia Majority, support this measure. “In our racially discriminatory criminal legal system, in order to really bring racial justice to the ballot box, the only way to assure that is to get rid of that old Jim Crow provision completely and make sure that the fundamental part of democracy is protected for all and everybody has a right to vote, 18 and over,” Claire Gastañaga, executive director of the ACLU of Virginia, told me.

She added, “We can’t be in a position where government gets to choose who votes. We need to be in a position where we decide who the government is.”

Others have proposed intermediate steps. McAuliffe told me in September that the legislature should codify his 2016 executive action and automatically restore voting rights upon completion of a sentence. “The governor should not be involved, it should be automatic,” McAuliffe said. Gastañaga echoed this point that voting rights can’t be up to a governor “deciding to be nice.”

In its 2020 session, the Virginia legislature took no action on either version of these changes. But no time was lost, state advocates told me, because reforming felony disenfranchisement requires activating Virginia’s lengthy constitutional amendment process: Two consecutive legislatures must pass an amendment, before it is placed on the ballot. So lawmakers would need to adopt a measure in 2020 or 2021, and then again in 2022 or 2023.

“Our goal is to have it pass in 2021, then in 2022, and on the ballot for voters in November 2022,” said Nguyen of SJ8. She described its introduction this year as “an organizing tool to use as we organize ‘right to vote’ chapters across the state, which is an effort being primarily driven by returning citizens.” She added, “This is an opportunity to lay a stake in the ground and say that voting rights are for everyone.”

Virginia’s newly Democratic government adopted other voting-rights laws in 2020; it enabled automatic and same-day voter registration, restricted voter ID requirements, and made voting by mail easier.

Gastañaga warned that future legislatures could try to erode these accomplishments, and she touted SJ 8 as enshrining the right to vote against broader encroachments than felony disenfranchisement. “The only thing that will prevent them to do that is a constitution that says that you have a right to vote that cannot be abridged by law,” she said.

—

Upon taking power in states besides Virginia, Democrats have prioritized adopting a similar slate of voting-rights measures.

But only over the last year did laws against prison gerrymandering join that immediate voting-rights agenda. (So far only Democratic-run states have adopted such laws.) This trend has coincided with the increased salience of reforms that deal with felony disenfranchisement.

Still, some bills against prison gerrymandering derailed in that same timeframe. In Connecticut and Oregon, they ran into lawmakers representing districts that contain prisons, and which stand to lose some political clout. “The problem when we talk about mass incarceration is that we can’t bring every voice to the [State] Capitol because many of them are behind bars,” Connecticut Senator William Haskell, a Democratic proponent of ending prison gerrymandering, told me last year.

Forty-one states remain that have taken no action against prison gerrymandering. Seven have fully Democratic governments, including Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, and Rhode Island; in Massachusetts, Democrats have a veto-proof majority.

The clock is ticking for them to act by the next decennial redistricting, which is scheduled to happen over the next two years. By delaying the census, COVID-19 may slightly postpone states’ timeline in a way that gives this reform additional time.