Political Report

A D.A. Runoff Will Decide New Orleans’ Criminal Justice Future

In the nation’s incarceration capital, activists push for a prosecutor who will make sweeping reforms.

In the nation’s incarceration capital, activists push for a prosecutor who will make sweeping reforms.

For advocates of criminal justice reform in New Orleans, the Dec. 5 district attorney runoff election holds an opportunity to upend policies that funnel people into jails and prisons in the incarceration capital of the United States.

“We are at a crossroads in our community,” said Gregory Manning, a pastor in the Broadmoor neighborhood. “It cannot be simply that we continue to lock people up and allow the criminal justice system and the jail system and the bail bondsman to benefit financially off of the incarceration of our people, especially African American people, people of color.”

Manning is a member of The People’s DA Coalition, a joint effort of more than two dozen criminal justice reform groups in the city.

Throughout the primary campaign, four DA candidates felt the heat from local organizers. They faced demands to appear at forums and commit to a wide set of decarceral measures put forth by the coalition. And they broadly responded by expressing sympathies for the group’s goals, a rupture from the rhetoric of the departing DA, Leon Cannizzaro.

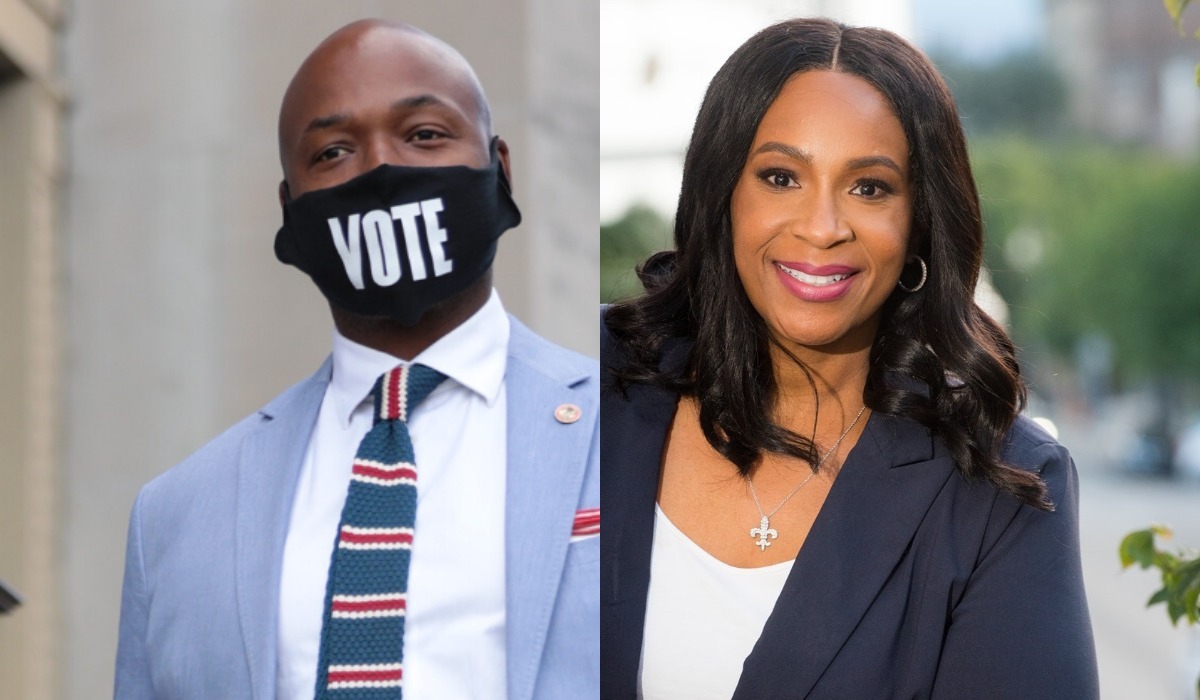

On Election Day, none of the candidates garnered more than 50 percent of the vote. Now, Keva Landrum, a former criminal court judge who led with 35 percent of the vote, and Jason Williams, a member of the City Council who received 29 percent, are running head to head.

Both have talked about advancing reforms, but their positions and records reveal a divide in how they would likely approach being a DA. Williams has promised more of a clean break with the office’s punitive past and embraced the People’s DA platform enthusiastically.

—

Earlier this year, Cannizzaro announced he would not run for re-election, throwing open the race for one of the most powerful public offices in New Orleans.

During his tenure, Cannizzaro relentlessly reinforced the state’s carceral norms. He attacked efforts to bail people out of jail pretrial, fought to retain nonunanimous jury convictions, vowed to put more children in jail, and used habitual offender laws to increase sentencing. He is also facing a lawsuit that alleges his office issued fake subpoenas to jail crime victims and to pressure witnesses to cooperate.

“Louisiana and New Orleans, in particular, have been such an epicenter of draconian sentencing, racially disparate conviction rates and indictment rates for drug charges, for juvenile prosecutions, for life without parole, for habitual offender enhancements,” said Chris Kaiser, advocacy director of the ACLU of Louisiana. “All of these are things that a DA can unilaterally choose to reform on their own without the need to wait for broader policy reform from the legislature or city council.”

Williams has worked as a criminal defense attorney with the Innocence Project New Orleans and championed criminal justice reforms as a City Council member. He pushed for a bail reform measure to lower the jail’s pretrial population, led the charge on reducing penalties for marijuana possession, and sponsored a successful ordinance to bring funding for the public defender’s office closer to parity with the DA’s office.This month, the City Council passed a 2021 budget that falls short of the funding requirements, but still gives a major boost to the public defender’s office.

However, Williams is facing a serious hurdle. This year, he came under a federal indictment for tax fraud. The trial date for the case is Jan. 11, 2021.

Williams has pleaded not guilty and he dismisses the charge as politically motivated. In October, he told The Appeal: Political Report that voters view the indictment as “an old-school political tactic” and that “I paid my taxes for all of those years that they’re talking about.”

Landrum briefly served as DA from 2007 to 2008 before running for criminal court judge. Cannizzaro succeeded her in 2008.

Last year, when Landrum was chief judge of the criminal court, she criticized Cannizzaro for blocking efforts to reduce the jail population through pretrial services. But at other times she has played a role in Cannizzaro’s agenda. The Lens found that she signed off on prosecutors’ controversial material witness warrants in at least 14 cases. And now Landrum shares some of the same campaign donors and endorsements as the retiring DA.

—

During her campaign this year, Landrum said she would never seek the death penalty, one of the tenets of the People’s DA platform. Williams has also vowed to not seek death sentences, closing the door to capital punishment in New Orleans no matter the outcome of the runoff.

But on other important issues, Landrum has pushed back against reform policies and warned that her opponent would not be harsh enough in some cases. She also promised to be “tough on violent crime,” a continuation of the DA office’s highly punitive status quo.

This messaging matches parts of Landrum’s record. During her time as DA, she drew fire for coming down hard on marijuana possession. She prosecuted repeat offenses as felonies, charges that could result in five to 20 years in prison. Before her term, the office routinely treated such cases as misdemeanors, which carry much lower penalties. Critics accused her of racking up felony convictions to make it appear that the DA’s office was tackling violent crime after New Orleans was declared a “murder capital.”

Landrum turned down an interview request by the Political Report for this story and did not submit responses to questions via email in time for publication. In October, Landrum told the Political Report that she disagreed that she had a punitive record.

Her platform this year does not detail what she would do regarding drug-related offenses. In 2019, drug charges made up over 30 percent of all new prison admissions in Louisiana.

On marijuana specifically, she said she would send cases to municipal court or else decline to charge them, a commitment that still fell a step short of several of her rivals’ commitments to drop all marijuana possession charges.

Williams, unlike Landrum, has run on dropping all marijuana possession cases.

When it comes to other drugs, Williams told the Political Report that he would prioritize diversion and treatment options over imposing incarceration. (Some prosecutors around the country have run on ending charges for drug possession altogether.)

“I don’t believe that courts and jails have ever provided any real intervention as it relates to addiction,” Williams said in a Zoom interview. “My goal is going to be to find ways to have these cases diverted from court to a diversion program that would have robust Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous, therapy, other community service measures.”

—

Another contributor to mass incarceration is excessive sentencing. In Louisiana, nearly 40 percent of those imprisoned are serving maximum sentences that exceeded 20 years. However, there is little proof that lengthy sentences meaningfully prevent crime.

“All the evidence for several decades points to the fact that people, even for violent offenses, age out of crime, so there is no reason that we need to be sending people to prison for life,” Kaiser, of the ACLU of Louisiana, said.

Prosecutorial decisions by the district attorney fuel these long sentences. If the district attorney chooses to use the “multi-bill” statute, Louisiana’s habitual offender sentence enhancement, then minimum sentences would be increased for people with past convictions. And in Louisiana, charges like second-degree murder carry a mandatory minimum sentence of life without the possiblity of parole.

“In our state, [life without parole] means you literally get carried out in a pine box,” Williams said. He said his office would be more stringent about bringing second-degree murder charges, which historically have been used very broadly to lock up people who are accused of being accomplices.

“We want to have that conversation long before the case is set for trial, so you can make sure that you’re using a charge that takes into consideration the harm caused to the victim, but also takes into consideration that a person who makes a poor decision at 21 probably is going to be a very different human being by the time they are 60 or 50,” Williams said.

Williams has said he would never use the habitual offender statute.

Landrum, by contrast, told The Political Report in October that she would still make use of the habitual offender statute, though she added she wishes to limit its use to “exceptional circumstances with supervisory approval.”

According to the magazine Antigravity, lawyers familiar with her practices told the magazine that Landrum regularly inflicted high bonds and long sentences as a criminal court judge.

Although the effect of harsh sentencing can be measured by the number of incarcerated people serving maximum or life sentences, it is not possible to measure its effect as a prosecutorial tool to compel plea deals.

“The statistics don’t show you the number of people who maybe had a habitual offender enhancement hanging over their head when they decided to agree to apply for a lesser charge,” Kaiser said. “We have every reason to believe that’s a lot of folks.”

As a result, Kaiser says, many people get stuck in the legal system rather than fighting their charges—another factor that contributes to the wide reach of Louisiana’s prison industrial complex.

This disproportionately impacts Black Louisianans who are incarcerated at four times the rate of white people in the state.

—

In New Orleans, the starkest racial divides in incarceration show up in the juvenile criminal legal system: 97 percent of juvenile arrests in New Orleans are of Black youth.

As with adults, the DA decides how to charge these arrested youth. Cannizzarro sent hundreds of children to adult court; between 2011 and 2015 he transferred over 80 percent of eligible cases involving 15- and 16-year-olds. As a City Council member, Williams criticized this practice.

During the primary, Williams committed to not transferring minors to adult courts even when they were charged with serious crimes. Landrum told the Louisiana ACLU that she would only charge youth as adults “in extreme circumstances” but did not elaborate on what that would entail.

Chief Public Defender Derwyn Bunton represented minors when Landrum was in charge of the DA’s juvenile division, as well as when she was interim DA. He said Landrum transferred youth to adult court in nearly all eligible cases.

“When, as a prosecutor, she has the advantage, she uses that advantage for conviction,” Bunton said in an interview with The Political Report. “She’s a prosecutor’s prosecutor.”

One particular case that stuck out to him was that of Travan Jones. In 2007, 15-year-old Jones was implicated in a murder. Bunton thought juvenile court could have been rehabilitative for Jones, but Landrum transferred his case to adult court where he was charged with second-degree murder, which carried a mandatory life without parole sentence. Jones eventually plead guilty to manslaughter.

“[There needs to be] a real holistic approach,” said Ernest Johnson, director and co-founder of Ubuntu Village which works with youth affected by the criminal legal system. Poverty, trauma, and other factors need to be taken into consideration when looking at the criminal activity of children, he said.

Johnson helped co-write the Platform for Youth Justice which provides guidelines for reforming the juvenile justice system through the district attorney’s office. The platform calls for not transferring minors into adult courts and prisons, and recommends developmentally appropriate ways to hold them accountable.

Manning, the pastor and member of The People’s DA Coalition, echoed Johnson’s view that the next New Orleans DA should address the factors underlying crime.

“Where do we begin to look at those factors and say, OK, what’s the root cause? Why is this happening?” he asked. Manning said poverty was among the root causes of violence, which means there is a need for more investment into community initiatives as opposed to harsher prosecution.

The People’s DA Coalition and other local groups have made these issues central to the DA election and have mobilized communities to get involved. Grassroots organizing has also shaped local judicial elections that delivered two public defenders to the bench in November, and an ongoing battle over jail expansion.

Kaiser said this kind of organizing is necessary to counter the powerful influence of the bail industry and others that stand to profit from tough-on-crime policies.

“For our part, what we can do is to elevate the power of people who are affected by these policies … and try to build political power as a counterweight to that,” he said.

“We need folks in office who are going to go above and beyond what the minimum requirements are in law, and think really boldly about how to end mass incarceration in this state.”