Political Report

One Week’s Work: New Jersey and Kentucky Restore Voting Rights to More than 200,000

More than 200,000 people regain their voting rights, and advocates vow further action. “To vote has value to the soul,” a New Jersey advocate said at a signing ceremony.

Advocates in both states vow further action against felony disenfranchisement. “To vote has value to the soul,” a New Jersey advocate said at a signing ceremony.

More than 200,000 people with criminal convictions regained the right to vote over the past week, as Kentucky and New Jersey struck a double blow against felony disenfranchisement.

—

On Wednesday, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed into law a bill to enable any adult citizen who is not incarcerated to vote. People on parole and probation were disenfranchised until now. The law, effective by the 2020 presidential primary, will restore the rights of about 80,000 people.

Ron Pierce, the Democracy and Justice Fellow at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice (NJISJ), is among those whose voting rights will be restored by this law. “I’m just beginning to process that I’ll be able to vote next year,” Pierce said at the signing ceremony on Wednesday. “To vote has value to the soul.”

Ryan Haygood, the president of NJISJ, told me afterward: “We have not been waiting for democracy to come from Washington D.C. down. Instead our strategy was, from the ground-up in our communities build democracy here in New Jersey.”

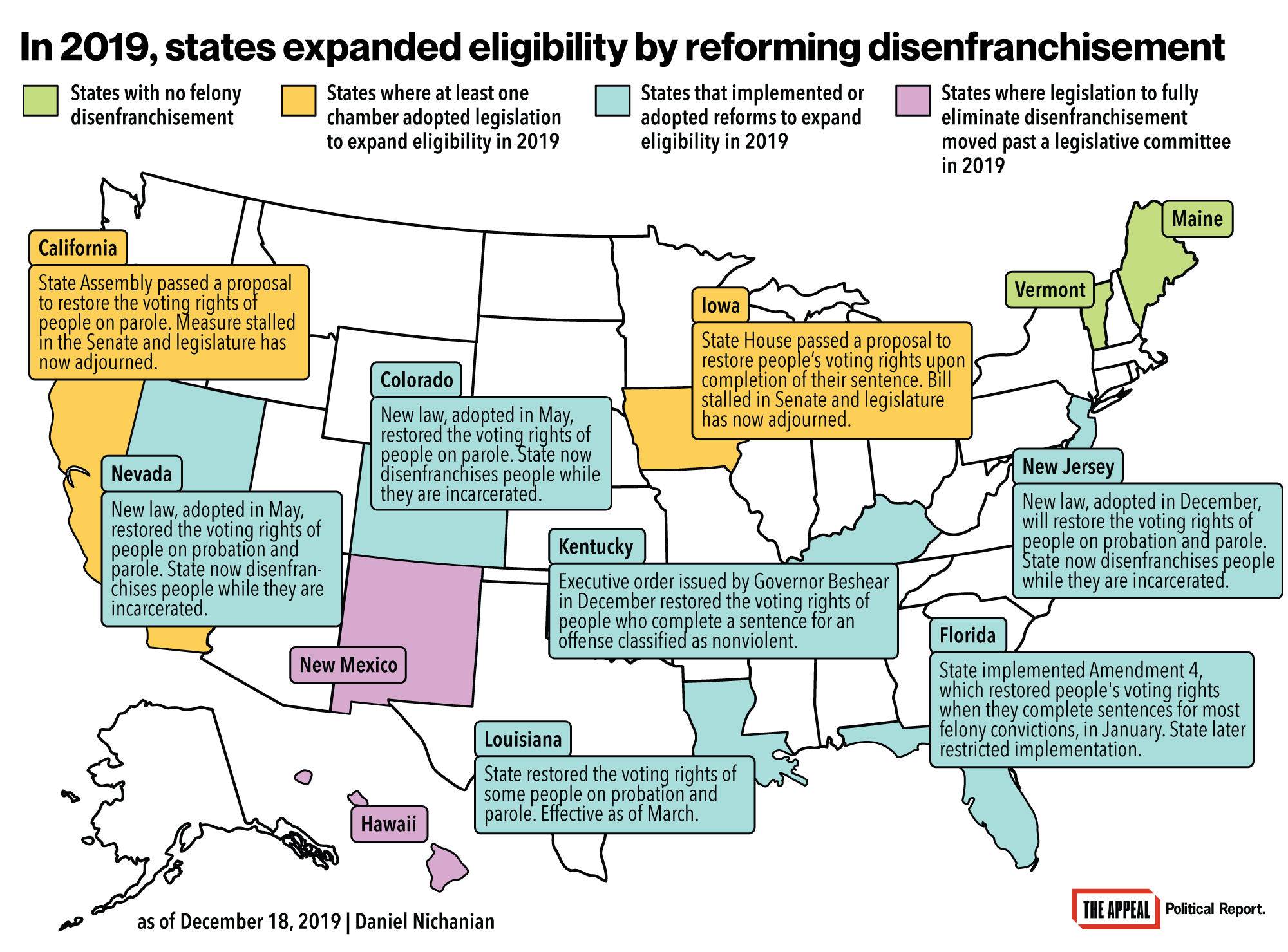

Colorado and Nevada adopted similar laws in the spring. This has all raised to 18 the number of states that enfranchise any adult citizen who is not in prison. That number includes Maine and Vermont, which also allow people to vote from prison.

State advocates have characterized the new law as important, but also as incomplete since it does not fully abolish disenfranchisement. “It’s a first step, there will be many many more excellent steps around that,” Newark Mayor Ras Baraka said during Wednesday’s signing ceremony.

New Jersey lawmakers ignored an alternative bill to enable incarcerated people to vote. Going forward, disenfranchisement in the state will still disproportionately affect African Americans. According to a 2016 study by the Sentencing Project, New Jersey has the nation’s largest racial disparity in incarceration; 60 percent of incarcerated people are Black, compared to 13 percent of the voting-age population. “We’re acknowledging that historically this policy is rooted in deep racism, and we’re saying, ‘OK, so let’s get rid of 70% of it’?” Alexander Shalom of the ACLU of New Jersey told the Philadelphia Inquirer last week.

Haygood, whose institute championed the new law while also demanding an end to disenfranchisement, agrees. “We will not be ‘1844 no more’ until we totally disentangle voting from our criminal justice system,” he said. (1844 is the year New Jersey both excluded people with criminal convictions and restricted the franchise to white men.) “Because we connect voting to that criminal justice system, we literally in fact link our political process with those racial disparities, with that racial discrimination. So the next phase is the push to connect incarcerated people with the right to vote, as they do in Maine and Vermont.”

Efforts to end disenfranchisement have gained steam this year. Lawmakers filed bills nationwide, and a growing number of public officials, including members of Congress and prosecutors, are endorsing that stance.

—

Last week, on his third day in office, Kentucky’s new Democratic governor Andy Beshear issued an executive order: Kentuckians who complete a sentence for a felony classified as nonviolent will have their voting rights automatically restored. In doing so, he fulfilled a campaign promise.

While this is a more modest step than taken by New Jersey, its effects will be considerable because of the state’s exceptionally exclusionary rules.

Until Beshear’s order, Kentucky was one of only two states, alongside Iowa, with a lifetime ban on voting for individuals convicted of any felony. (Other states enforce a lifetime ban over some but not all felonies.) As of 2016, the state disenfranchised 26 percent of Black adults, and 8 percent of the rest of its adult residents.

The order is expected to cut those numbers by more than a third, restoring the voting rights of an estimated 140,000 people. That’s about 4 percent of the state’s adult population.

Kentucky’s action leaves Iowa as the only state that will enforce a lifetime voting ban following any felony conviction. Governor Kim Reynolds, a Republican, has refused to issue an executive order ending this arrangement. While she has simplified the process by which Iowans can petition for their rights, Laura Belin reports that her changes have had little effect.

Reynolds has restored the voting rights of fewer than 300 people after nearly three years in office; Beshear reached an estimated 140,000 in just three days.

But Beshear’s policy is limited as well. It excludes people convicted of a crime categorized as violent; at least 100,000 Kentuckians who have completed their full sentence will thus remain disenfranchised, and this number will only grow.

Advocates with Kentuckians for the Commonwealths and the ACLU of Kentucky had called on Beshear to go further during his election. Since he did not heed their call, Kentucky will retain one of the nation’s more restrictive systems. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe made no such distinctions in his own rights restoration initiative in 2016. “Once someone has completed what the judge and jury decided the sentence or penalty should be, that should be the determinant,” he told me in September.

Hinging people’s eligibility to vote on the exact statute under which they were convicted poses a range of problems. Besides the overbroad nature of the nonviolent/violent distinction, studies show that prosecutors are likely to file higher-level charges against Black people. Racial disparities increase at every stage of Kentucky’s criminal legal system. In addition, Beshear’s order is likely to effectively keep away even some of the people it enfranchises. Nationwide, many are eligible to vote but think they are not or are unwilling to risk it, a dynamic exacerbated by the confusing and technical rules people must navigate, often with little assistance from public authorities and with the looming threat of criminal prosecution.

—

New Jersey and Kentucky’s actions come six months after Colorado and Nevada adopted back-to-back laws of their own expanding voter eligibility, and a year after reforms in Florida and Louisiana signaled that the ground is rapidly shifting on this issue.

Kentucky’s debate is far from over. Beshear called on the legislature to codify his order into law. The idea has bipartisan support, but the GOP leadership has repeatedly killed it over the past decade.

2020 is also expected to bring renewed efforts elsewhere, including over proposals to end disenfranchisement in New York and Washington D.C., a possible constitutional amendment in Virginia, and measures against prison gerrymandering.