Political Report

These Twelve Elections Could Curb ICE’s Powers

In many places that have long helped arrest and detain immigrants, voters will decide the fate of local partnerships with ICE, possibly dealing a series of blows to the agency.

In many places that have long helped arrest and detain immigrants, voters will decide the fate of local partnerships with ICE, possibly dealing a series of blows to the agency.

Immigrants’ rights activists have been protesting local officials that help ICE arrest and deport immigrants, pressuring them to end those ties, and candidates for these offices have felt the heat.

Most significantly, their work has upended the usually quiet landscape of sheriff’s races, helping drive upset losses for longtime incumbents in places such as Minneapolis and Charlotte, North Carolina, in 2018, and already this year—in spring primaries—in Cincinnati and in Athens, Georgia.

Will November’s general elections add to that trend?

The GOP’s declining fortunes in longtime conservative bastions that have soured on President Trump—who has made hostility to immigration one of his defining rallying cries—have opened the door to political turnover in areas such as Atlanta’s northern suburbs. Those areas were long impregnable to Democrats and any candidates running on cutting ties with ICE. Elsewhere, some Democratic-leaning jurisdictions face a reckoning over their ICE-friendly policies.

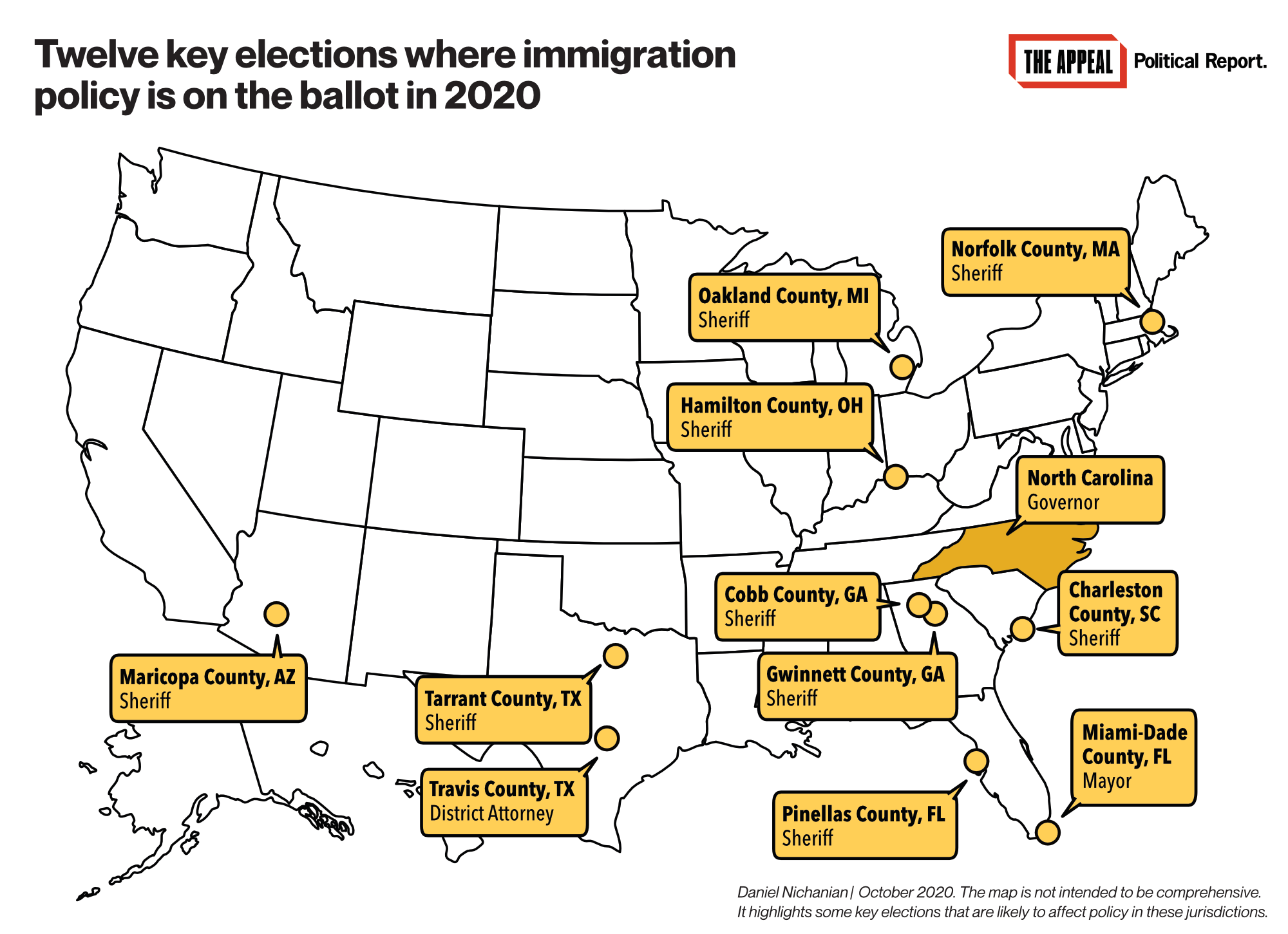

Below I look at 12 of the most important state and local elections on the ballot this fall that will affect ICE’s reach and local immigration policy.

The list covers different sorts of offices. But the lion’s share are races for county sheriff. These officials have tremendous discretion on whether and how to respond to or collaborate with ICE. That’s because most sheriffs are responsible for running local jails, which hundreds of thousands of people go through every year, often with little to no oversight from other public officials. And these jails are a major funnel into the country’s deportation machine, especially when a sheriff is keen on making them so, as The Appeal: Political Report explained in July.

For one, most sheriffs have sole authority over whether their county joins ICE’s 287(g) program. This partnership directly implicates sheriffs in harming immigrant communities by authorizing their deputies to act like federal immigration agents. Only 145 counties in the nation have 287(g) contracts at this moment, but that pool includes very populous jurisdictions—and that’s precisely where Nov. 3 could upend the local landscape: In counties that cover millions of residents—in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Texas—candidates are running this fall on a promise of terminating existing 287(g) contracts. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Sheriffs also decide whether they will agree to detain ICE prisoners in exchange for payments; and whether to honor so-called ICE detainers, which are warrantless requests asking sheriffs to keep jailing a person past their scheduled release to give federal agents time to arrest them.

All of these arrangements are on the line on Election Day, and with them the prospect that voters may slash ICE’s reach, as they did in 2018, regardless of what happens in the presidential race.

Arizona | Maricopa County (Phoenix) sheriff

No local official is as closely associated with repressive immigration practices as Joe Arpaio, Maricopa County’s sheriff from 1993 to 2017. Arpaio ran a detention facility known as Tent City that he himself called a “concentration camp,” and he engaged in racial profiling in defiance of a court order. Arpaio was ousted in November 2016 by Democrat Paul Penzone, who subsequently closed Tent City, and Arpaio fell short in his attempted comeback this year, narrowly losing to Jerry Sheridan in the Republican primary. But Sheridan is Arpaio’s former lieutenant, and could carry on Arpaio’s legacy if he beats Penzone in November. Writing in the Political Report, Jerry Iannelli stresses that Penzone has disappointed immigrants’ rights activists over his first term. But he also reports that Republican nominee Sheridan is directly implicated in the racial profiling of the Arpaio years and he has vowed to reopen Tent City.

Florida | Pinellas County (St. Petersburg) sheriff

Bob Gualtieri has been an enthusiastic champion of ICE, both through his powers as the sheriff of Pinellas County and through his leadership role in the state’s Sheriffs Association. He helped design a new arrangement for Florida sheriffs to circumvent legal concerns and keep detaining people when ICE requests it; and he has contracted his office into ICE’s 287(g) program. Gualtieri, a Republican, faces Democratic challenger Eliseo Santana who has vowed to terminate both of these partnerships if he is elected sheriff and to reject forms of discretionary assistance with the agency. “I will not have my agents be the agents of destroying families in our community,” Santana told me in a Q&A last week. “These types of agreements are hurting our community, are destroying the family, and it’s anti-American.”

Florida | Miami-Dade mayor

In January 2017, as President Trump entered the White House and took aim at “sanctuary cities,” Miami-Dade County’s Republican Mayor Carlos Giménez announced a major policy reversal that has helped ICE target undocumented immigrants: The county, Florida’s most populous, would honor ICE detainers by holding people in jail beyond their scheduled release if federal agents request it. (Local governments typically leave the discretion on this matter to sheriffs, but Miami-Dade is the only jurisdiction in the state that does not have one.)

The candidates vying to replace him, Republican Esteban Bovo and Democrat Daniella Levine Cava, have long been on opposite sides of this change. Both were county commissioners in February 2017 when the commission ratified Giménez’s order, despite hundreds of residents demanding a return to sanctuary policies. Bovo voted to approve the order, and Cava opposed it. Cava is now running on curtailing cooperation with ICE, including fighting a new state law that mandates that local law enforcement assist the federal agency. “I think it’s overreach and a pre-emption on how we take care of our people,” Cava said at a summer forum.

Georgia | Cobb County sheriff and Gwinnett County sheriff

Cobb and Gwinnett, two counties in the Atlanta suburbs that have a combined population of over 1.5 million, have undergone a similar transformation. Longtime Republican bastions with harsh policies toward immigrants, they voted Democratic in the 2016 presidential election for the first time since 1976, a change fueled in part by a significant rise in the local Latinx population. Now these counties’ legacy of tightly helping ICE will be tested, Timothy Pratt wrote in the Political Report in September. The Republican sheriffs of Cobb and Gwinnett have both joined ICE’s 287(g) program. And in each county, the November election pits a Democrat who has committed to terminating the 287(g) contracts against a Republican who wants to stay in the program. But even if the program falls, advocates say, far more policy upheaval will be needed to stop the repression of the region’s immigrant communities.

Massachusetts | Norfolk County sheriff

Jerry McDermott and Patrick McDermott, no relation, are facing off on Nov. 3. Jerry, the Republican incumbent, was appointed by the governor two years ago. Patrick, a Democrat, is the county’s registrar of probates. The incumbent championed a ballot initiative last year that would have undone a state court ruling and authorized sheriffs to honor ICE detainers, which come without a judge’s signature. He did not respond to a request for comment on how he would partner with ICE if elected to a full term. By contrast, and as I reported in the Political Report in August, his challenger says sheriffs should not honor ICE requests that a federal judge has not signed, and that he would not enter into new contracts like a 287(g) agreement. “These contracts make it harder to ensure that all members of the communities … feel safe and secure,” he said.

Michigan | Oakland County sheriff

Sheriff Mike Bouchard, a Republican in a county that may be poised to reject President Trump in November, has honored ICE’s detainer requests, and as a leader in the Major County Sheriffs of America, he has worked to extend that practice throughout the country. “If ICE is coming after someone in the jail, it’s for a criminal charge,” he told Detroit News in 2017, downplaying the fact that most people in jail have not been convicted. In November, Bouchard faces Democratic challenger Vincent Gregory, a former state senator who told the Political Report that he would break with Bouchard’s policy on detainers. “I would NOT honor the request from ICE to hold the prisoners without a Court Order,” he said in an email. But Gregory also volunteered that immigration has not been central to conversations he has had during the campaign, and he does not feature the issue on his website.

North Carolina | Governor

In 2018, buoyed by the activism of advocacy groups such as Comunidad Colectiva, Action NC, El Pueblo, or Siembra NC, North Carolina saw a wave of wins by sheriff candidates—all Black Democrats—who ran on cutting ties with ICE in five of the state’s most populous counties. They promptly did just that upon entering office. This enraged Republicans, who run the state legislature. Last year, they passed a bill to require that sheriffs collaborate with ICE. But Democratic Governor Roy Cooper vetoed the legislation, effectively protecting sheriffs’ ability to not do ICE’s bidding. Cooper is up for re-election against Republican Lieutenant Governor Dan Forest. If Forest wins, it would likely hand the GOP control of the state government, enabling them to revisit the 2019 bill. But the state could also swing in the other direction; a Cooper win may be accompanied by legislative gains for his party, strengthening the new sheriffs’ hand.

Ohio | Hamilton County (Cincinnati) sheriff

This is the only election featured here that has a candidate who wants to scale back collaboration with ICE, and one who wants to ramp it up. The incumbent sheriff, Jim Neil, is a Democrat who attended a Trump rally in 2016, honors ICE detainers, and has faced protests from activists. He could not overcome that record in the Democratic primary, losing to Charmaine McGuffey, a former sheriff’s deputy who is running a reform-minded campaign, as Teresa Mathew reported in the Political Report. McGuffey told Mathew that she would no longer honor detainers if elected.

Now McGuffey faces Republican Bruce Hoffbauer, a police lieutenant who has said the county should be even more active in partnering with ICE than it has been under Neil; he did not respond to a request for comment on how he intends to partner with ICE, though. (Neil has endorsed Hoffbauer since his primary defeat.) Hoffbauer is also running on increasing enforcement against what he calls “street-level crimes” such as drug offenses, which could increase arrests and jail bookings. This approach to policing, combined with a goal of helping ICE arrest people held in the local jail, could lead to even more people being funneled into deportation proceedings.

South Carolina | Charleston County sheriff

Charleston County may have voted for Democrats in the last three presidential elections, but it also has a Republican sheriff, J. Al Cannon, who has made it one of ICE’s closest allies in the state. Charleston is one of only four South Carolina counties in ICE’s 287(g) program, enabling deputies to facilitate defendants’ transfer into ICE custody. Cannon also has an agreement to detain people that ICE arrests elsewhere, including during raids, which has drawn protests. This record is on the line in November. Cannon, who has been in power since 1988, faces Kristin Graziano, a sheriff’s deputy he put on leave when he learned that she was running against him.

Graziano, a Democrat, told me this week that she would “immediately” terminate the 287(g) program. “It’s contradictory to what we’re trying to accomplish in Charleston,” she said, namely “building our communities back up and building trust.” She added that she would not honor ICE detainers, and would “end completely” agreements that involve detaining people on non-criminal grounds. Graziano, whose website takes the rare step of laying out her views in both English and Spanish, said she has “learned” from “dialogue” with advocates from the Latinx community, whom she wants “sitting at the table making the decisions that affect their lives.”

Texas | Tarrant County (Fort Worth) sheriff

In this county of nearly two million residents, Republican Sheriff Bill Waybourn has been a vocal cheerleader for Trumpian immigration politics. Speaking at a White House event in 2019, he praised ICE for “standing on the wall between good and evil for you and me,” and defended jailing people who face criminal charges on immigration grounds because otherwise “these drunks will run over your children and they will run over my children.” But Tarrant County has rapidly shifted toward the Democratic Party during the Trump era, and this has made Waybourn vulnerable to Democratic challenger Vance Keyes, a former police officer who says he is running to end the incumbent’s “fear mongering tactics.” The ICE out of Tarrant County coalition has fought Waybourn’s participation in ICE’s 287(g) program. Keyes has vowed to terminate it if he is elected.

Tarrant is by far the most populous Texas county in 287(g). There are only two other 287(g) counties that were carried by a Democrat in a federal race in either 2016 or 2018, a mark of potential competitivenss: Williamson County (Georgetown) and Nueces County (Corpus Christi). In each, the incumbent sheriff is a Republican with a Democratic opponent; but neither of the challengers answered my requests for comment on their views on immigration and 287(g), nor do they indicate a position on their website, in a stark contrast with Keyes’s willingness to tackle the issue in Tarrant.

Texas | Travis County (Austin) district attorney

Travis County may elect as its next DA a candidate who describes himself as an “immigrant rights activist.” José Garza, a former public defender and leader of the Workers Defense Project, an organization focused on labor and immigration law, ousted the incumbent DA by an overwhelming margin in the Democratic primary. He is now favored against Republican candidate Martin Harry, given the county’s large Democratic lean. Garza told me in June that he wants to avoid immigration consequences for people facing criminal charges or convictions. “A simple proposition for me is that no one should face a more severe punishment simply because of their status,” he said, noting that for some cases it would be a matter of keeping the penalty for a crime under one year, which is a threshold that triggers deportation.

—

This is not an exhaustive list of every local election whose result will shape immigration policy; there are thousands of elected offices that will be decided on Nov. 3. I have selected elections in counties that are at least somewhat politically competitive, as well as elections that pit candidates with clear political differences.