Political Report

In Northwest Arkansas, Activists Organize Against ICE’s 287(g) Program

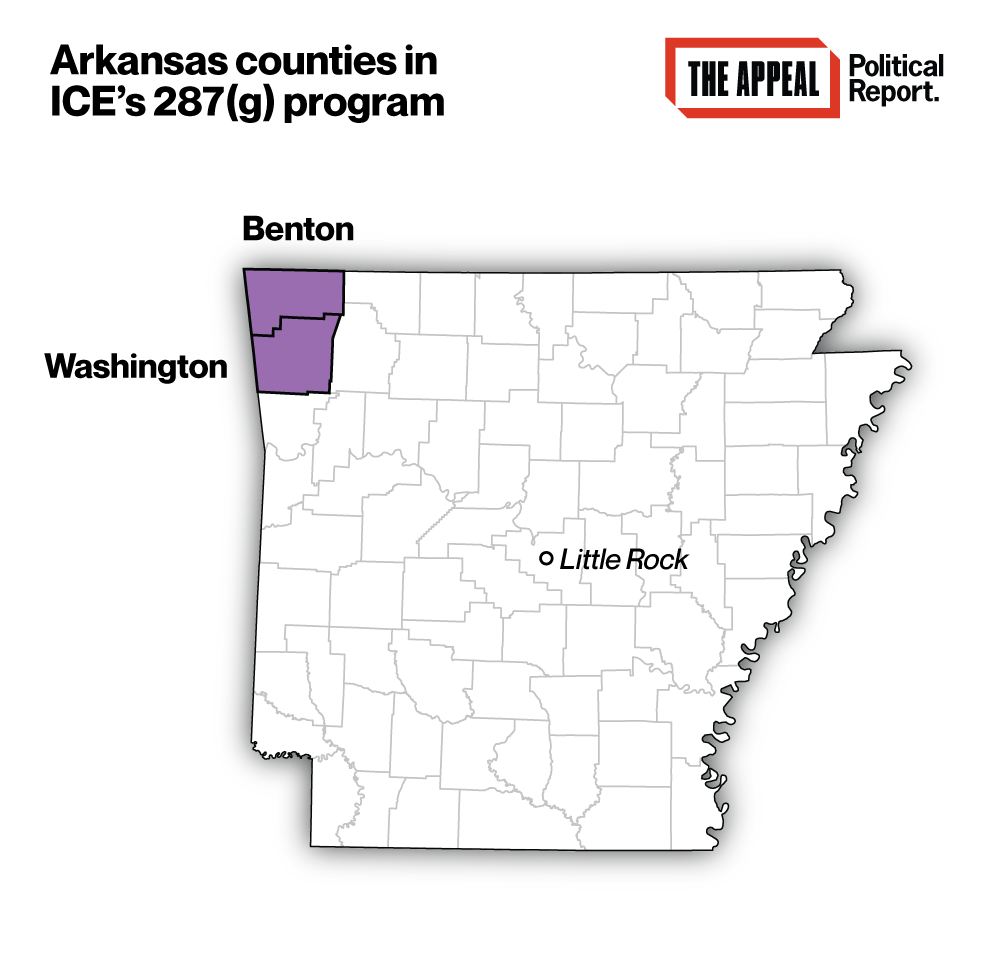

Two counties in northwest Arkansas joined the 287(g) program with ICE more than a decade ago. A coalition of local groups is organizing to end that cooperation.

This article is part of a series on 287(g) contracts in states.

Two counties in northwest Arkansas (Benton and Washington) joined ICE’s 287(g) program more than a decade ago. A coalition of local groups, which include People Power Washington County, Arkansas United, Workers’ Justice Center, and Catholic Charities Group, is organizing to end that cooperation.

In December, activists transformed the usually muted public forum that 287(g)-participating counties must hold annually into a crowded protest. This got the local press to at least feature voices explaining the program’s impact on separating families and on throwing people into prolonged detention and deportation proceedings.

The 287(g) program authorizes local law enforcement to research the immigration status of people they detain. “ICE doesn’t have the human capacity, they don’t have enough people to enforce immigration law, so what they do is they rely on collaborations with local law enforcement,” said Juan José Bustamante, an associate professor of sociology and Latin American and Latino studies at the University of Arkansas who also takes part in local organizing. “What the local community can do is make accountable local political officials, and that includes the sheriff’s departments, mayors, quorum courts, and what have you … to make them accountable about the outcome and the injustices that this collaboration produces.”

Benton County Sheriff Shawn Holloway and Washington County Sheriff Tim Helder have direct authority over renewing or terminating the program. Both were re-elected in 2018, and are next up for re-election in 2022.

Helder is a longtime Democratic sheriff who applied for a 287(g) contract in 2007 and has renewed it ever since. He skipped the December meeting.

Holloway, a Republican, attended it and said afterward that he was open to further conversations and to reviewing the program. Benton County’s 287(g) contract was last renewed in 2016, before Holloway became sheriff, but he has chosen to maintain his county’s participation. He faces an active choice later this year since the contract expires in June. His office did not respond to a request for comment.

Speaking with the press in December, Holloway praised 287(g) for identifying “violent criminals.” Local officials often use such rhetoric, playing on the fact that 287(g) screens people who are at the county jail. But many of the people processed through the agreement are arrested for low-level offenses, including traffic violations. Even Helder, who is a strong proponent of the program, acknowledged this in a 2017 interview. “Not everyone is going to be a drug dealer or rapist or a bank robber,” he said. “There will be people that come through our doors that may have a warrant for a misdemeanor offense.”

That concession aside, Helder has misleadingly conflated crime and illegal immigration in defending his policies. “We recognized that we have problems with a high influx of illegals in the area, and I think that along with that came the criminal element,” he said in 2010, long before President Trump emerged on the political scene.

Blanca Estevez, an immigrants’ rights activist in Washington County who attended the December meeting, said immigrant communities have lived under Helder’s policies long before Trump’s victory, but public attention toward them has grown significantly since 2016, specifically among white residents. “I’ve been at the steering committee meetings where it’s been just me and nobody else for years,” she said, adding that “it was so great” to see a crowded room last month.

Local officials other than the sheriff have some leverage, too. Quorum courts (the state equivalent of a county commission) set the sheriff’s budget, for one. Washington County’s quorum court approved a significant increase to Helder’s budget last year, and his requests have again been central to the county’s budget discussions this winter. Mireya Reith, the founding executive director of Arkansas United, called on the quorum courts to use this authority to pressure the sheriffs or to order an audit of the 287(g) program’s financial impact.

Organizers told me that one challenge they have faced is that elected officials tend to not take Latinx constituents as seriously as white residents. Another is that the national climate and the mistrust toward law enforcement caused by the 287(g) program have repercussions on activism. “We find power in numbers, but there is still that fear in the community,” Reith said. “Our community doesn’t feel they have rights. … Our community believes that they will be fired and somebody will call ICE if they turn out.” Reith added that these perceptions are compounded by broader political dynamics in the state. There is “a concerted effort in Arkansas since the civil rights movement to give activism and organizing a bad name,” she said. “The idea of hitting the streets as activism has a bad name.”

Estevez concurred. “We constantly put people through these ringers just to prove their humanity and that they are deserving of humanity just like anyone else who was born across an invisible line,” she said.