Political Report

From Marijuana to the Death Penalty, States Led the Way in 2019

A retrospective on the year that was on criminal justice reform. Seven maps. 16 issues. 50 states.

A retrospective on the year that was on criminal justice reform. Seven maps. 16 issues. 50 states.

State legislatures this year abolished the death penalty, legalized or decriminalized pot, expanded voting rights for people with felony convictions, restricted solitary confinement, and made it harder to prosecute minors as adults, among other initiatives.

But criminal justice reform remains an uneven patchwork. States that make bold moves on one issue can be harshly punitive on others. And while some set new milestones, elsewhere debates were meager—and in a few states driven by proposals to make laws tougher.

The Political Report tracked state-level reforms throughout 2019. Today I review the year that was—by theme and with seven maps. And yes, each state shows up.

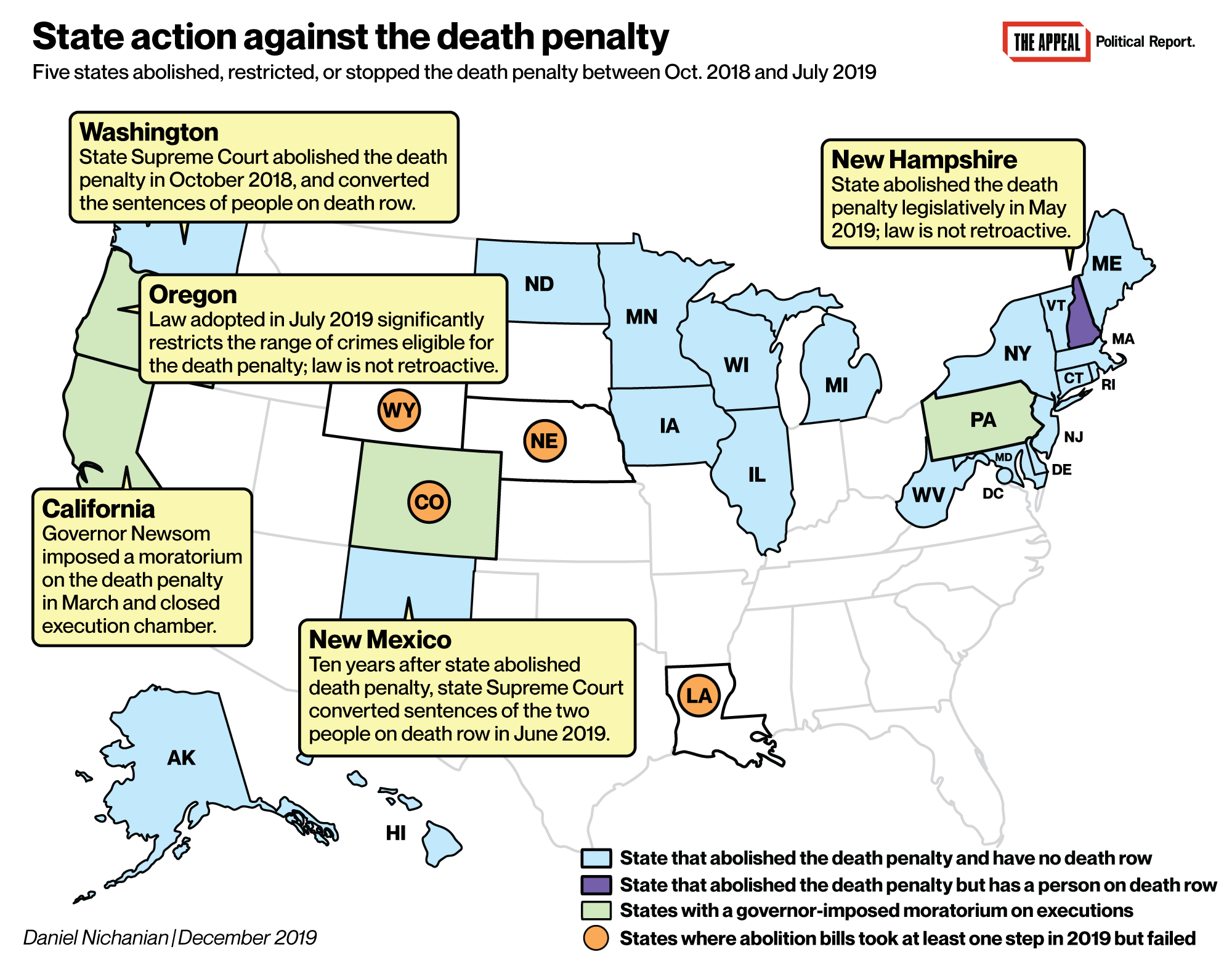

Death penalty

While the Trump administration is attempting to restart executions, momentum built against the death penalty at the state level. Five states restricted, halted, or repealed the death penalty over a 10-month period that began in October 2018, when the Washington Supreme Court abolished the death penalty and converted the sentences of the people on its death row.

Then, in March of this year, California Governor Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, imposed a moratorium on executions. Prosecutors can still seek death sentences, though, and people remain on death row.

New Hampshire abolished the death penalty in May, becoming the 21st state to do so. This was a hard-won victory for death penalty abolitionists, who overcame a veto by Republican Governor Chris Sununu with no votes to spare in the Senate thanks to significant gains in the 2018 midterms.

In June, the New Mexico Supreme Court converted the sentences of the last two people on the state’s death row. (New Mexico abolished the death penalty 10 years ago.)

Finally, in July, Oregon considerably narrowed the list of capital offenses. This is not retroactive, and leaves 30 people on death row; advocates have asked the governor for commutations.

Other states considered abolition, and Wyoming came the closest—just a few votes short in the state Senate. Also: In Ohio, a bill to ban the death penalty for people with mental illness stalled in the Senate after passing the House; and legislation to require unanimous juries in Missouri failed. Arkansas was a rare state to adopt a law conducive to the death penalty; it made it a felony punishable by up to six years in prison to “recklessly” identify the makers of drugs used for an execution.

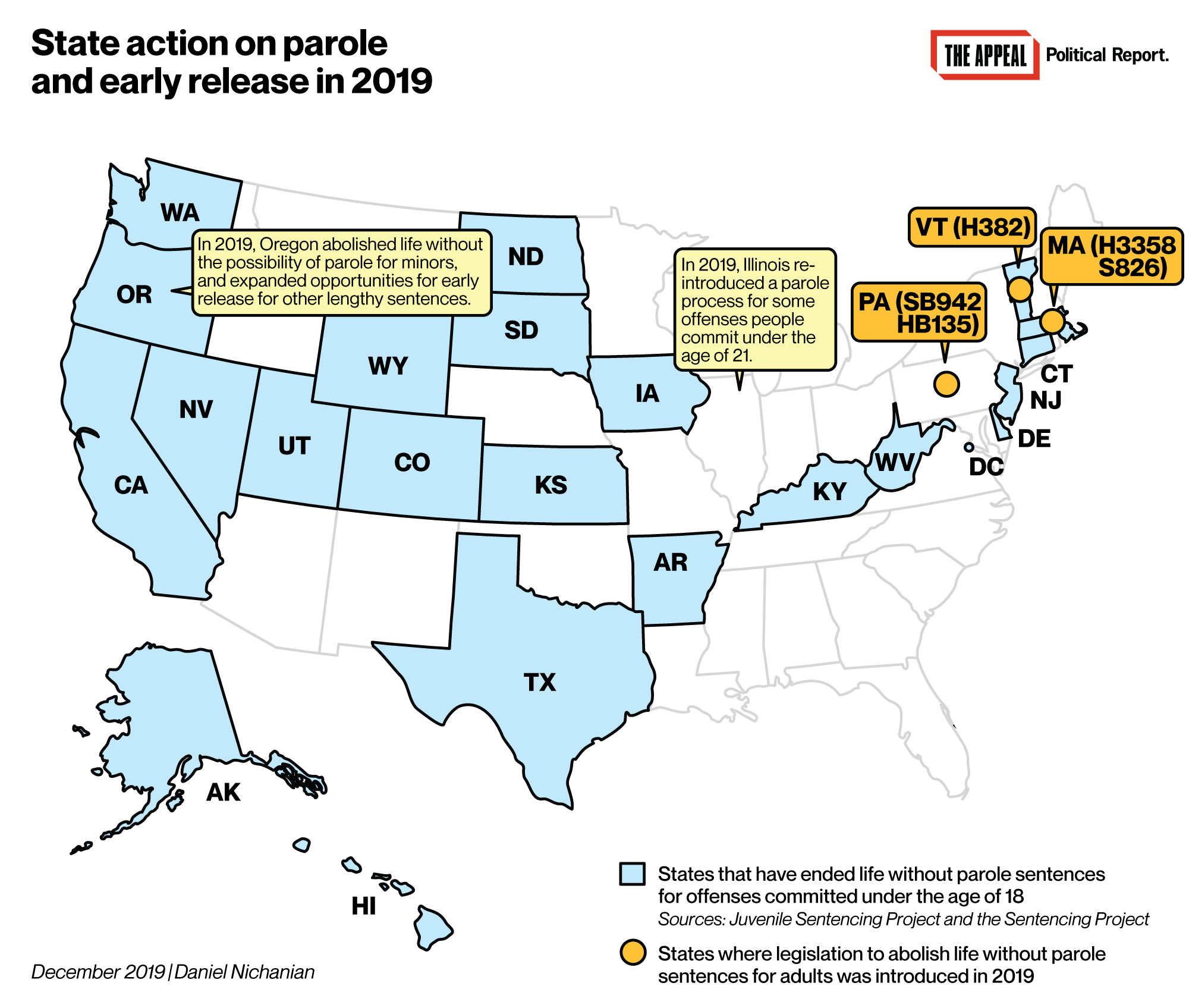

Parole and early release

The movement against the death penalty was accompanied by a nationwide push against death by incarceration, namely sentences that leave people virtually no chance of ever being released.

In Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, reformers championed bills to abolish sentences of life without the possibility of parole; these bills would have guaranteed that everyone will be at least eligible for release after some lengthy period of incarceration. They did not pass, but they expanded debates around long sentences. Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, commuted the life sentences of eight people this month, reviving a power that had ground to a halt.

Oregon abolished juvenile sentences of life without the possibility of parole, namely for acts that people committed as minors. This increased the number of states that have repealed those sentences to 22 (plus Washington D.C.). But similar bills failed elsewhere, from Democratic-run Rhode Island to Republican-run South Carolina. Oregon’s law also confronted other types of lengthy sentences, creating new opportunities for early release or a revised sentence for people convicted of offenses they committed as minors. This is not retroactive, though, and state advocates are asking lawmakers to revise that.

In Illinois, which eliminated its parole process in 1978 and left many to spend decades in prison with no opportunity for release, a new law changes that paradigm: It will make most people convicted of offenses they committed before the age of 21 eligible for parole. While the law is narrow, advocates told me in April that they see it as a jumping-off point.

Hawaii came close to amplifying these efforts. But Governor David Ige, a Democrat, vetoed a bill to let people suffering from a terminal or debilitating illness request a medical release.

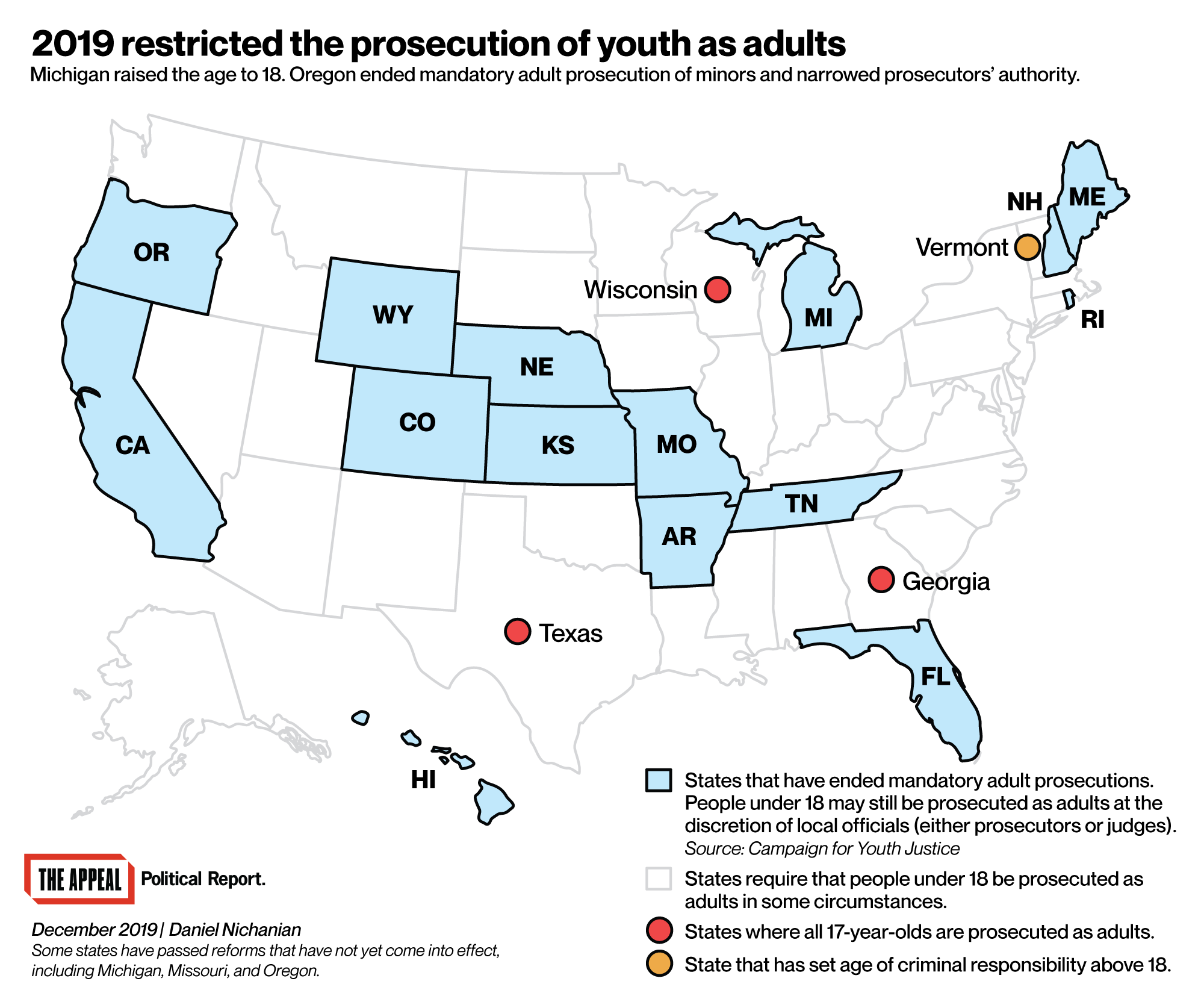

Youth justice

In 2019, a pair of laws cut the number of teenagers who will be tried as adults. The youth justice system, despite major problems of its own, has a comparatively rehabilitative outlook.

First: mandatory prosecutions. In Oregon, a wide-ranging law repealed all requirements that some minors be prosecuted as adults. Such mandates triggered long sentences for teenagers above 15. (Advocates clinched a supermajority they had long sought for this reform, in a dramatic sequence.) While Florida also ended mandatory adult prosecutions this year, Oregon’s law took another major step: Rather than empower district attorneys to solely decide when to try minors as adults, it forces them to first obtain a judge’s approval.

Second: age eligibility. Michigan raised the age until which teenagers can be in the youth system by one year, to 18. Until now, the state treated every 17-year-old as an adult. Michigan prosecutors retain wide discretion to transfer them into adult court, however.

Michigan’s reform left only three states that have passed no law raising the age to 18 (Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin); each state saw unsuccessful efforts to change that this year. But in some states, the debate has already moved ahead, and advocates are asking why being a day over 18 should cut off access to the youth justice system. In 2016, Vermont passed a law to steer some people up to age 21 to its juvenile system. This year, Massachusetts debated a similar bill with support from three of the state’s DAs; and Illinois passed an early-release law that atypically used 21, rather than 18, as its cutoff point.

Also this year: North Dakota raised to 10 from 7 the age at which children can be referred to the juvenile system, Maryland made it harder to detain children under the age of 12, New York made it easier for 16- and 17-year olds to stay in family court, and Washington restricted the detention of children over noncriminal acts like truancy.

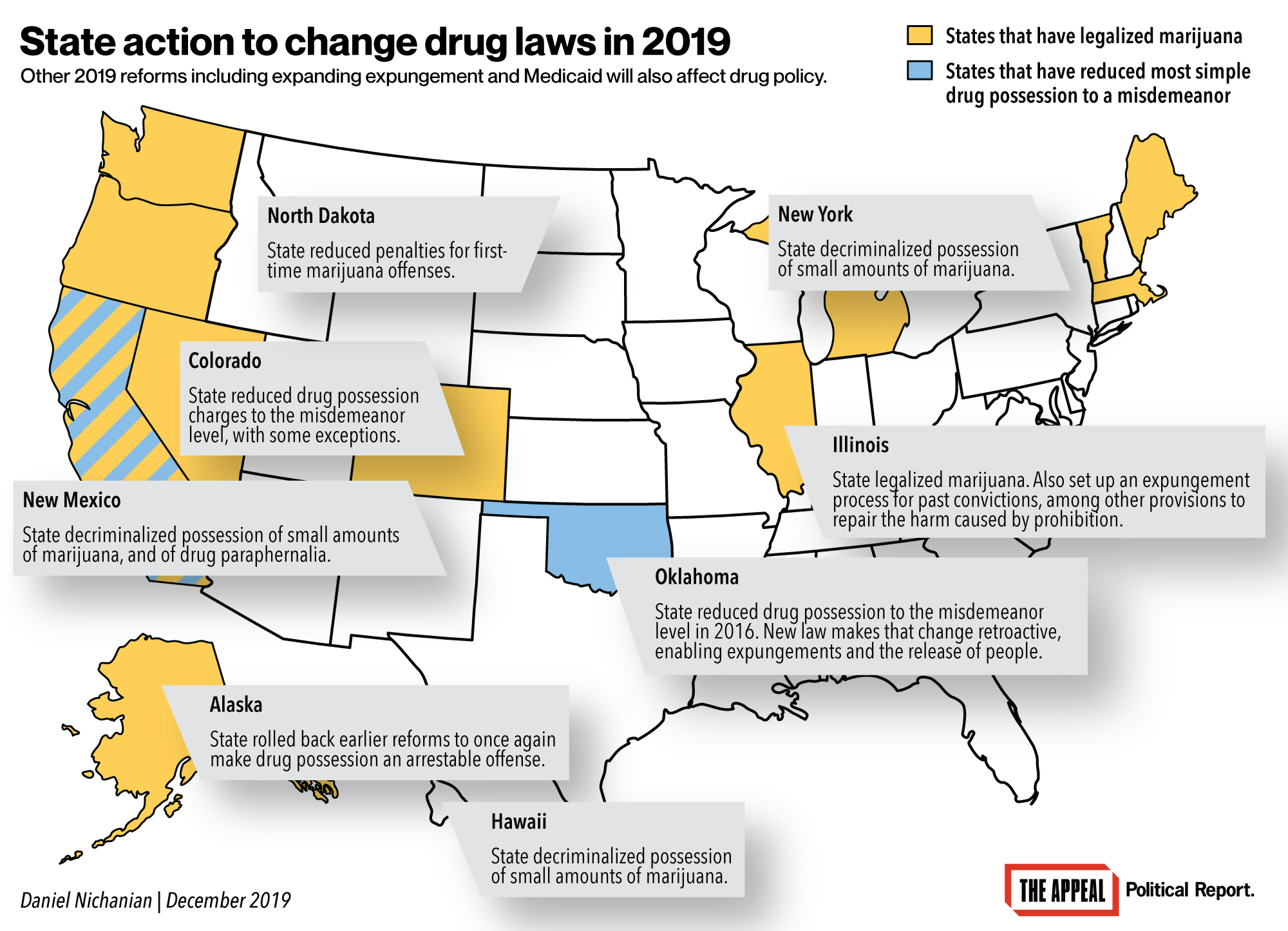

Drug policy

Marijuana legalization reached a new milestone in 2019: Illinois became the first state to create a regulated pot industry legislatively. Until now, this had only been done via popular initiatives.

Illinois also set up a process for people to get old marijuana convictions expunged, and adopted measures to help them enter the pot industry (though advocates warned these are insufficient); some of the revenue will be redistributed to areas with a high share of people with convictions. Here as elsewhere, advocates called such equity provisions essential to repairing some of the harm caused by prohibition, especially against African Americans.

Other states also reformed their marijuana laws to varying degrees. Hawaii, New Mexico, and New York decriminalized the possession of small amounts of marijuana. North Dakota reduced penalties, and removed jail time for first-time offenses. And Florida repealed its ban on smokable medical marijuana. But in Texas, and elsewhere, promising reform efforts stalled.

Colorado and Oklahoma led the way when it came to drug reforms beyond marijuana.

Democratic-governed Colorado made possession of most drugs a misdemeanor rather than a felony, which will reduce penalties and sentences going forward. (Advocates also prioritized a “defelonization” bill in Ohio, though it has yet to move.) Oklahoma already adopted this “defelonization” change in a 2016 referendum; this year, lawmakers made it retroactive. This reform is significant: Republican-governed Oklahoma is only the second state to retroactively defelonize drug possession, after California. This will reduce the existing prison population. Hundreds of Oklahomans quickly became eligible for release.

Alaska was a rare state to take a more punitive turn, rolling back earlier reforms to once again make drug possession an arrestable offense. A bill passed by Virginia’s GOP-run legislature to make it easier to prosecute overdoses as homicides was vetoed by the state’s Democratic governor.

Also: In states like Maine, Idaho, and Nebraska that expanded their Medicaid programs, and where lower-income individuals will have stronger access to health insurance, proponents cast the expansion as a way to combat the opioid crisis and better connect people to treatment for substance use. Kansas’s new governor, Democrat Laura Kelly, called for Medicaid expansion to “ease the unsustainable burden on our … criminal justice system;” her push has yet to succeed.

Prison conditions

New Jersey adopted the country’s strictest law against solitary confinement, setting a limit of 20 consecutive days and 30 days over a 60-day period. But this remains beyond the United Nations’ “Nelson Mandela Rules,” which bar solitary for more than 15 consecutive days.

Advocates pushed for similar legislation in New Mexico and New York. It was not taken up in New York. And in New Mexico, which has high rates of use of solitary confinement, legislative leaders considerably weakened the bill. The state did adopt important restrictions on the use of solitary against pregnant women, minors, and people with disabilities. Connecticut failed to set another major milestone: A bill that would have made it the first state with free phone calls from prisons derailed after a telecommunications corporation lobbied against it.

These events captured the difficulty of getting lawmakers to care about prison conditions. Some reforms that passed exemplify the low bar. “Things we didn’t know needed to be banned,” Vaidya Gullapalli wrote in The Daily Appeal when Oregon banned the use of attack dogs on people in prison.

Perhaps the lowest bar of all: Alabama prohibited its sheriffs from personally pocketing public money allocated to feeding people held in county jails. They could do so legally until now.

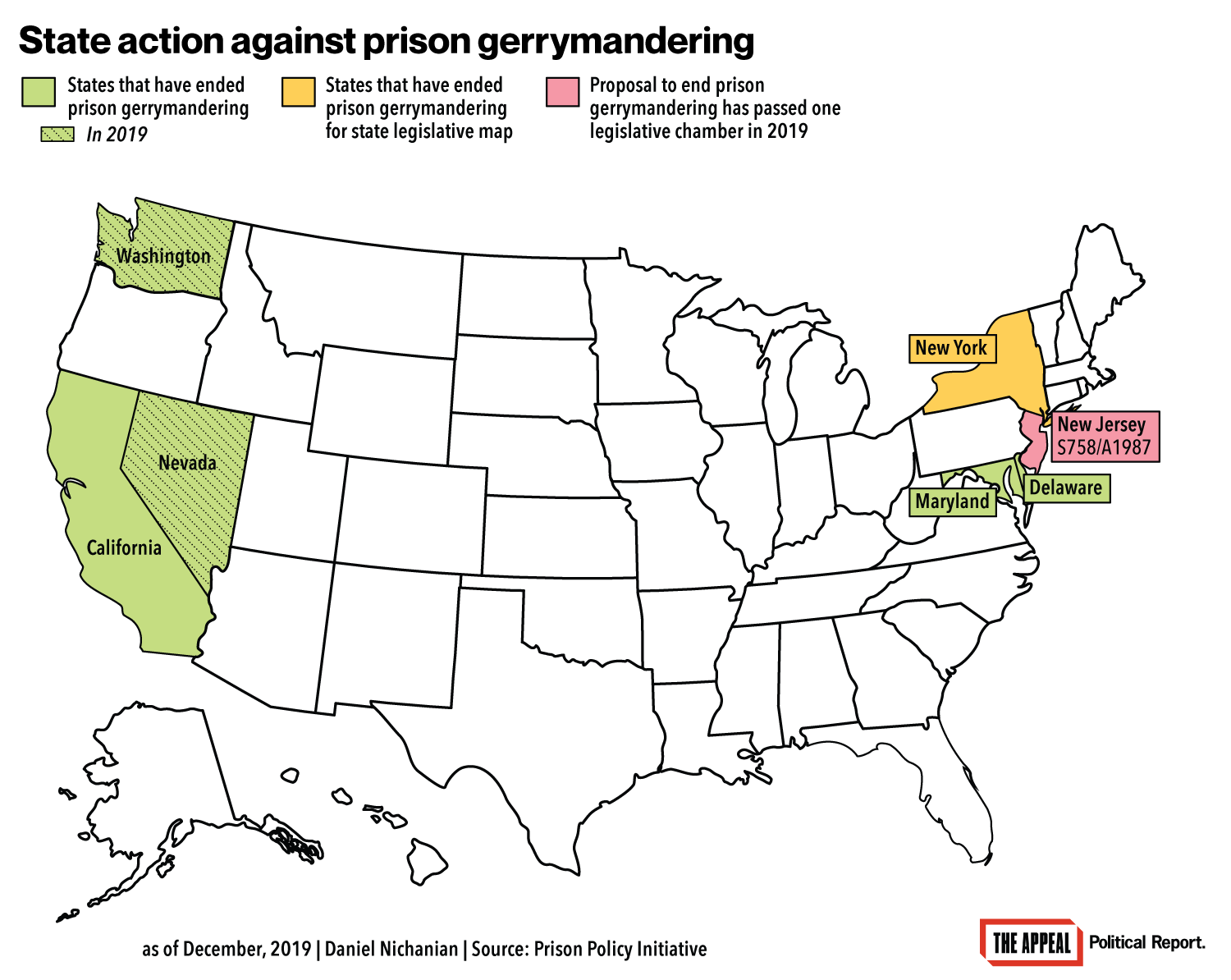

Prison gerrymandering

Nevada and Washington adopted laws to end prison gerrymandering, which counts incarcerated people at their prison’s location rather than at their last residence for purposes of redistricting. The practice inflates the power of predominantly white and rural areas, where prisons are often located.

Still, despite the backlash against skewed census counts and against gerrymandering, only six states have ended this practice. The clock is ticking, since states draw new maps in 2021.

Rights restoration and felony disenfranchisement

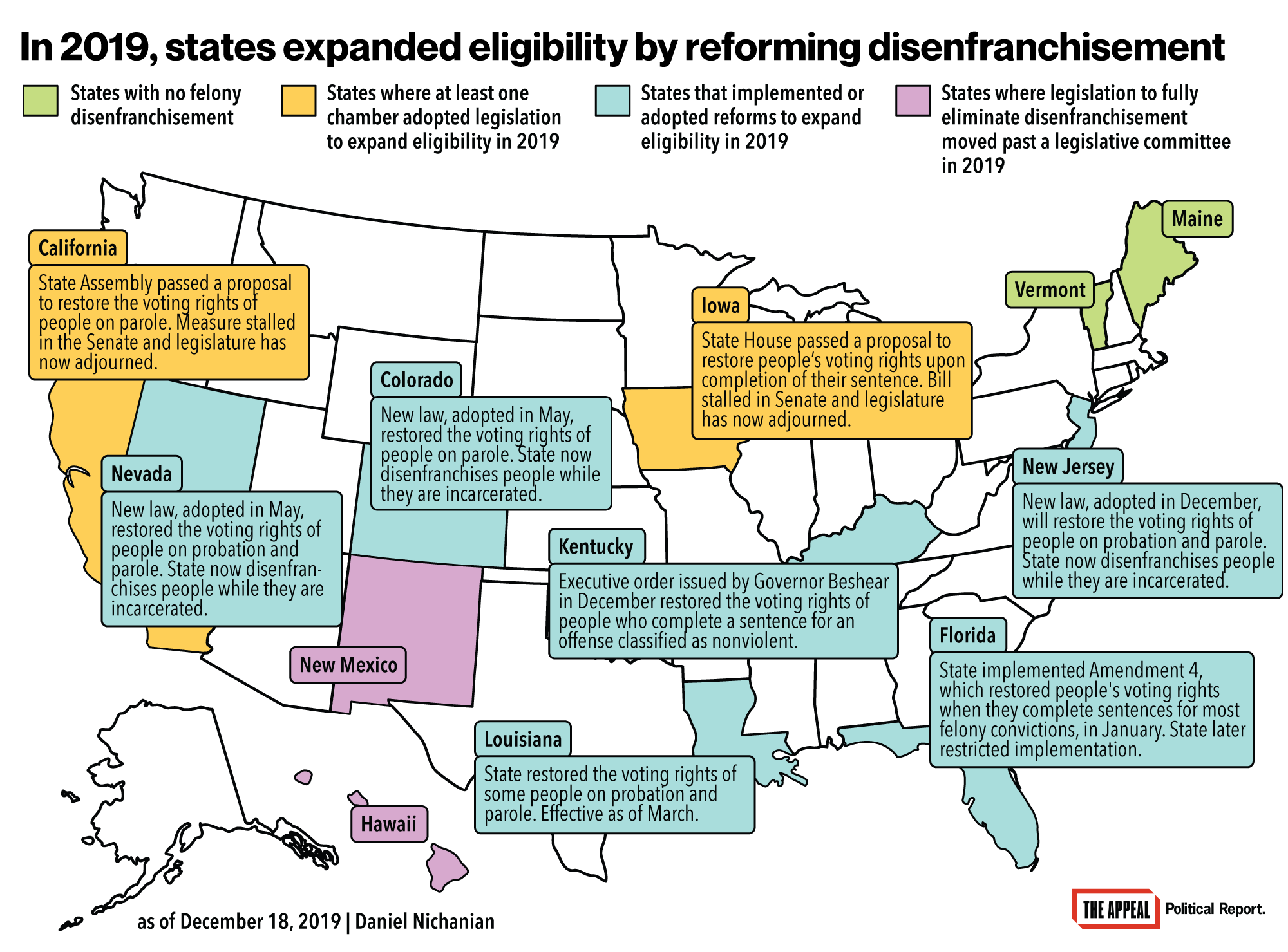

State politicians confronted felony disenfranchisement with new urgency in 2019, in the wake of Florida’s historic Amendment 4, which inspired advocates around the state this year, and of the 2018 prison strike, whose organizers demanded voting rights for people in prison.

Florida and Kentucky, two very restrictive states that were each enforcing lifetime voting bans against hundreds of thousands of residents with felony convictions, promoted rights restoration once people complete a sentence. Florida implemented Amendment 4, restoring the voting rights of most people who finish a felony conviction. But state Republicans narrowed implementation in May by requiring payment of outstanding court debt, setting off legal and political battles.

In Kentucky, Democrat Andy Beshear won the governor’s race and then promptly restored the voting rights of people who complete sentences for felonies classified as nonviolent. Tens of thousands of people who have completed their sentences will remain disenfranchised; still, 4 percent of Kentucky’s population regained the right to vote with just one stroke of the pen.

Beshear’s order leaves Iowa as the only state that enforces a lifetime voting ban over all felony convictions; legislation to reform that rule had momentum, but died in the Iowa Senate. Mississippi’s legislature similarly ignored a slate of bills that would have eased its harsh voting rules.

Three states went further to decouple voting and the criminal legal system: They enfranchised all voting-age citizens who are not incarcerated, including if they are on probation or on parole.

Only one state had passed such a reform this past decade (Maryland). But Colorado, Nevada, and New Jersey all did so this year. This brought the number of states that allow all adult citizens who are not incarcerated to vote to 18. (That number includes Maine and Vermont, where people can also vote from prison; they also can in Puerto Rico.) Also: Louisiana implemented a 2018 law that lets some people vote while serving a sentence. The secretary of state did not play an active role informing newly-enfranchised people of their rights, leaving the burden of outreach on grassroots groups.

In some states, advocates focused on ending felony disenfranchisement. This would end the practice of stripping people with felony convictions of their right to vote, including if they are in prison. Lawmakers in eight states plus Washington D.C. filed legislation to that effect. In Hawaii and New Mexico, these bills advanced past a committee; that was already historic since reform on this issue has traditionally been more incremental.

Also: Illinois adopted a law requiring prisons to better inform incarcerated people of their right to vote upon their release. On a parallel issue, California ended its ban on people with felony convictions serving on juries once they have completed their sentences.

Immigration and local law enforcement

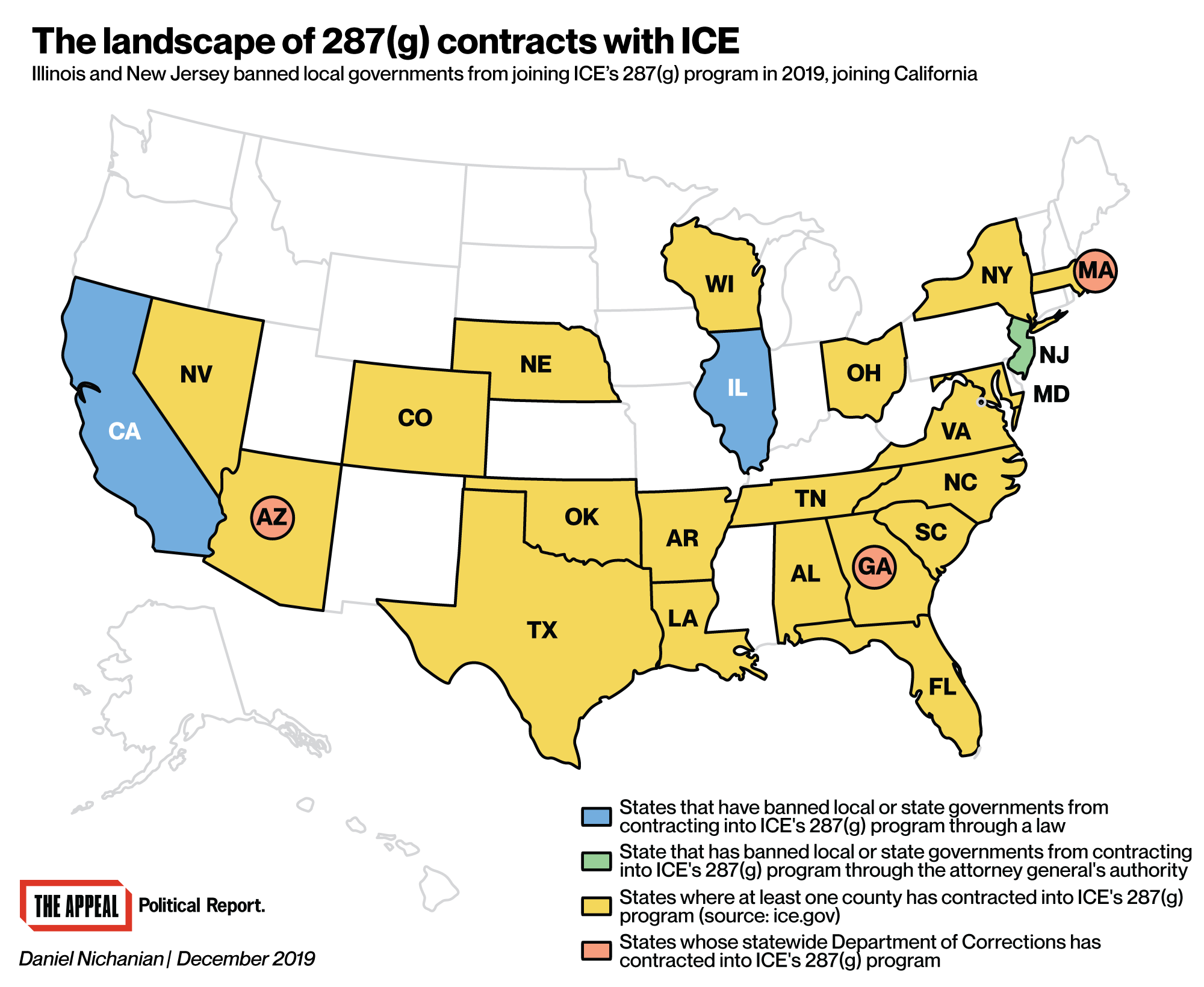

In Illinois and New Jersey, Democrats prohibited county governments from entering what may be the most visible form of partnership with ICE: its 287(g) program, which authorizes local law enforcement to act as federal immigration agents within county jails.

These two states join California as the only state to take such a step. This reform did not advance in other Democratic-governed states like Massachusetts and New York, both of which have state or local agencies with 287(g) contracts. In fact, Colorado Governor Jared Polis, a Democrat, threatened to veto such a ban, citing the value of local control.

Another major front regarding local law enforcement’s cooperation with ICE was the legality of “detainers,” which are ICE’s warrantless requests that jails keep detaining people beyond their scheduled release. Colorado Democrats adopted a law that forbids honoring detainers; in New Jersey, Democratic Attorney General Gurbir Grewal did the same, though he allowed for exceptions. Inversely, a law championed by Florida Republicans mandates that local law enforcement honor ICE requests; a full-throated effort by the North Carolina GOP to do the same failed because of Democratic Governor Roy Cooper’s veto.

Also: Colorado, New York, and Utah cut the maximum sentence for some or all misdemeanors by one day (from 365 to 364). This seemingly-small tweak will shield some people from deportation because noncitizens sentenced to at least one year of detention risk deportation.

Past records and expungement

Beyond their immediate sentences or fines and fees, involvement with the legal system restricts people’s access to housing, transportation or employment. In response, some states expanded opportunities for people to expunge their criminal records.

Take Delaware, which newly gave people the opportunity to expunge some convictions without first obtaining a pardon. Or West Virginia, which expanded eligibility to cover some felonies.

But most people eligible for expungement do not seek one, as the process is costly and burdensome. As such, one of the year’s important trends is the spread of “Clean Slate” laws that automate parts of the expungement process, shifting the burden onto the government.

After Pennsylvania became the first state to adopt such a law in 2018, Utah followed suit this year. California, besides starting to implement a law that automatically clears pot convictions, expanded automation this fall. (California’s Clean Slate law is not retroactive, unlike those of Pennsylvania and Utah, but its law is the only one to extend eligibility to some felony convictions.) Michigan and New Jersey have also begun the process of adopting Clean Slate laws.

Elsewhere, lawmakers lessened the tremendous impact that court debt has on the lives of people who cannot afford to pay it. Montana led the way, halting the suspension of driver’s licenses over a failure to pay fines and fees, a practice that can trigger mounting legal and economic hardships; Tennessee and Virginia passed more modest versions of this legislation.

California advocates were unsuccessful in their push for a bill that outright banned many fees; Newsom vetoed another bill that would have required judges to determine people’s financial ability before imposing fines and fees. In Florida, Republicans tied state politics more tightly to financial obligations by subordinating rights restoration to repayment of fines and fees.

Finally, responding to studies showing that restricting the residency of people convicted of sexual offenses is isolating and fuels homelessness, the GOP-run Wisconsin legislature unanimously passed a bill repealing those restrictions. But Governor Tony Evers, a Democrat, vetoed the bill.

And there’s more

On pretrial procedures, New York adopted two major changes: It ended the use of cash bail for people charged with misdemeanors and some felonies; it also required that DAs share evidence like witness statements within 15 days of a defendant’s first court appearance. These reforms’ implementation is a major question heading into 2020 given the resistance of many prosecutors. Also, Colorado prohibited cash bail in low-level cases, and required bond hearings within 48 hours of arrest.

On policing, a California law restricted the circumstances in which police officers can use deadly force, though some advocates questioned the reform’s scope. California also adopted a three-year moratorium on the use of facial recognition technology in body cameras. And New Jersey mandated that all cases of people killed by police be investigated by the attorney general rather than prosecutors.

On sentencing, proponents of reduced sentences had high hopes in Arizona but reforms either died in the legislature or were vetoed by Republican Governor Doug Ducey. By contrast: North Dakota repealed some mandatory minimums, California ended an automatic enhancement statute, Washington slightly narrowed its three strike law, and Delaware Attorney General Kathleen Jennings, a Democrat, overhauled sentencing guidelines. In South Dakota, the legislature defeated a tough-on-crime push to increase prison admissions.

On probation, Minnesota and Pennsylvania considered proposals to cap the length of probation, whose burdens often trip people up on small violations. But Pennsylvania lawmakers gutted the bill so much its champions turned against it; the Minnesota proposal never moved forward in the legislature, but its sentencing commission is now considering adopting it administratively.

On exonerations, a new Indiana will provide exonerated individuals $50,000 of restitution for each year they were incarcerated—but only if they agree to forego all litigation against the state.

On prosecutors, some lawmakers took steps for DAs to stop operating a black box. Connecticut became the first state to require that prosecutors collect an extensive collection of data about the decisions they are making. Louisiana reduced DAs’ power to jail victims of sexual offenses or domestic violence to compel them to testify. And California barred plea deals in which DAs ask defendants to forfeit hypothetical future rights, in response to a strategy that San Diego DA Summer Stephan was implementing.

On asset forfeiture, finally, Arkansas adopted the unusual rule of requiring that individuals actually be convicted of a felony before having their assets seized. And while it looked like Hawaii would do the same amid significant problems in the state’s system, Ige vetoed the bill.

Preparations are already well underway for 2020 legislative sessions, whether in Virginia, where newly-empowered Democrats are unveiling their agenda, in Maryland, where change in legislative leadership may make criminal justice reform more viable going forward, or in New York.