Cash Bail, Death Penatly, Pot: A 12-hour Span Brings Reform Milestones

The Appeal: Political Report’s February 25 newsletter

Feb. 25, 2021: Within a span of just a few hours this week, New Jersey legalized marijuana, Illinois adopted a law that will end cash bail, and Virginia lawmakers sent a bill that abolishes the death penalty to the governor. And that was just Monday. Today I review those milestones.

- Illinois: Governor signs omnibus bill into law, ending cash bail and bringing other changes

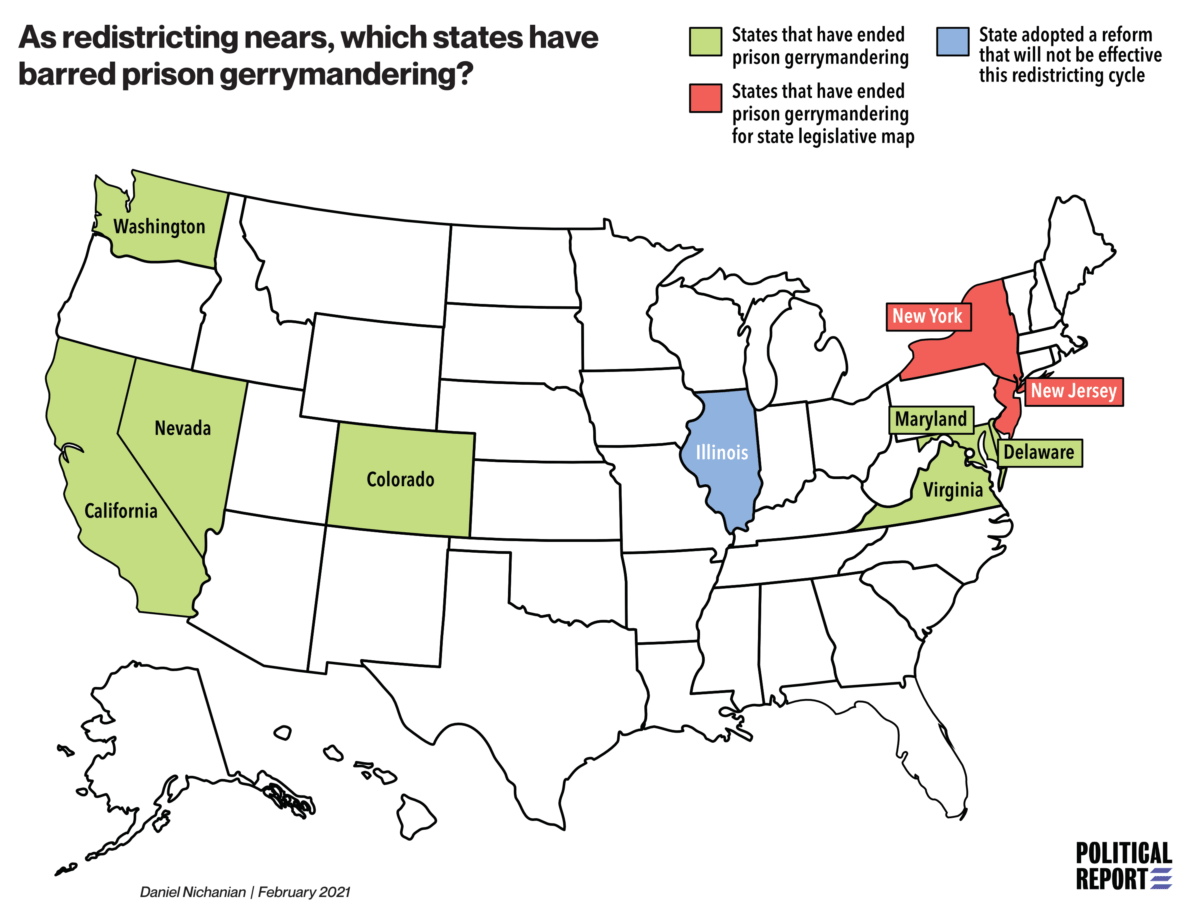

- Illinois: The new law delays the end of prison gerrymandering by a decade

- New Jersey: Four months after a successful referendum, the state legalizes marijuana

- New Mexico: House advances bills to expand voting rights and end qualified immunity

- Virginia: Abolition of the death penalty could come any moment now. Will other states follow suit?

- Texas: A new federal ruling protests race discrimination in jury selection, yet again

In case you missed it, catch up with last week’s Political Report newsletter. You can also visit our interactive tracker of legislative developments and our interactive tracker of the latest reforms being implemented by prosecutors nationwide.

Illinois: Governor signs omnibus bill into law, ending cash bail and bringing other changes

Governor J.B. Pritker signed into law on Monday an omnibus bill that upends many areas of the criminal legal system. The legislation, championed by the Legislative Black Caucus in the legislature’s lame-duck session in January, was years in the making due to the work of a large coalition of state activists and advocacy groups.

Here is an overview of some of its main components.

Bail reform: The law’s most emblematic provision is an end to cash bail. This means that Illinois will no longer connect pretrial release to the fulfillment of financial conditions that defendants are often unable to meet. Once the bill goes into effect, Illinois will be the first state to outright end cash bail. But that will not be until 2023. Safia Samee Ali reports for NBC News that reform advocates in the state are optimistic that the bill avoids some of the pitfalls of other states’ reforms, which replaced cash bail with rules that local advocates warned would not shrink pretrial detention. “Dare I say that it’s the most progressive piece of legislation that has been passed,” Sharone Mitchell, director of the Illinois Justice Project, told NBC News. Also, Isaac Scher reports in The Intercept that the Illinois law goes further than other states in limiting the use of algorithmic tools to make decisions about pretrial detentions, and in curtailing electronic monitoring as an alternative.

Driver’s license suspensions: As momentum builds nationally against suspending driver’s licenses for a failure to pay court debt, the Illinois law curtails the practice. People will no longer see their licenses suspended over unpaid red-light and speed camera tickets. The bill is meant to “restore the driving privileges of some 11,000 people by July and eliminate a significant trigger for personal bankruptcies in Chicago,” Melissa Sanchez reported in ProPublica in January.

Felony murder: The law will narrow the felony murder doctrine, but it will not bring relief to people already incarcerated because it will not apply retroactively.

Policing: The law makes a set of reforms to policing, such as requiring more thorough records of police misconduct. It also tightens certain rules, including a ban on chokeholds, though such statutes have been insufficient elsewhere given the broader context of impunity.

The law also contains a provision on prison gerrymandering, which I review at more length below.

|

Illinois: The new law ends prison gerrymandering, but not this decade For years, State Representative La Shawn Ford, a Democrat who represents parts of Chicago and Cook County, sponsored a bill to end prison gerrymandering in Illinois, and for years it went nowhere. This practice consists of counting incarcerated people at their prison’s location rather than their last residence for the purpose of redistricting. It skews political representation away from Chicago and Cook County, where incarcerated people disproportionately come from, and toward the whiter downstate areas where all Illinois state prisons are located. To make matters worse, people incarcerated over felonies cannot vote in Illinois, so their physical presence grows the clout of communities that they cannot influence. With prison gerrymandering, Ford says, “you’re counting bodies but you’re not giving them the care that they need.” Areas where prisons are located “don’t count [prisoners] when it comes to schools, hospitals, resources. They don’t count them as people. They only count them as numbers for the sake of using them for apportionment.” In January, the state legislature finally passed his bill as part of an omnibus package that contained many other changes to the criminal legal system (see above). Governor J.B. Pritzker, a Democrat, signed it this week. But a clause inserted into the law significantly delays implementation of the measure concerning prison gerrymandering. The bottom line is that the state’s district maps will not be fixed until 2031. Read the rest of my article on how prison gerrymandering skews political power in Illinois, on how advocates hope to address it, and on the related issues like felony disenfranchisement that amplify its effect. |

New Jersey: Four months after a successful referendum, the state legalizes marijuana

Legal marijuana is coming to New Jersey.

On Monday, Governor Phil Murphy signed into law a package of bills that legalize marijuana and implement the ballot initiative that New Jersey voters overwhelmingly approved in the fall. The new laws will set up a regulated system of marijuana sales; retail may be up and running by the end of this year.

In New Jersey, as elsewhere, the prohibition of marijuana has been enforced through extreme racial disparities.

State advocates emphasize that the new laws contain provisions meant to repair the harms of that racist enforcement. “[They] will advance racial and economic equity—a testament to the hard work of advocates, community organizers, and faith leaders from across New Jersey,” Reverend Dr. Charles Boyer, founding director of Salvation and Social Justice, said in a statement. Areas that have faced more arrests over marijuana will be designated as “impact zones” and receive more of the funding generated by mariuana sales, the Asbury Park Press reports.

The biggest sticking point in legislative negotiations was the rules for people under 21, who are barred from possessing or buying marijuana. The governor wanted the legislature to toughen penalties if they break that law, but Marijuana Moment reports that lawmakers resisted. The final compromise does not include civil penalties and fines, but it makes marijuana possession by someone under 21 subject to a written warning and referral to community service groups.

Will New Jersey’s decision bleed into other northeastern states? Joshua Vaughn reported in The Appeal in January that New York and Pennsylvania are facing more pressure to follow suit now that they stand to lose out on a lot of potential revenue to a neighboring state.

New Mexico House adopts bills to restrict disenfranchisement, end qualified immunity

Voting rights

In 2019, state advocates made a major push against felony disenfranchisement and thought they had momentum, but legislative leaders ended up not bringing a bill that would expand voting rights to the floor. The issue has already gone further this year: New Mexico’s House adopted a bill this month that would enable anyone who is not incarcerated to vote. It now moves to the Senate.

The measure would enfranchise people who are on parole or probation. (People who have completed their sentences are already allowed to vote in New Mexico, unlike in some other states.) More than 10,000 people were barred from voting in New Mexico last year because of restrictions that would be lifted by this bill, according to the Sentencing Project.

However, the House approved a late amendment introduced by a Republican lawmaker that qualifies the right to vote for some citizens who are not incarcerated. It requires that people whose sentence requires them to register as a sex offender have completed that step.

But the bill would continue to disenfranchise people who are incarcerated over a felony. In 2019, a New Mexico lawmaker introduced a bill that would enable people to vote from prison as well. “Prior nationwide reforms have chipped away at the disenfranchisement system rather than eliminating it altogether,” I wrote at the time. “Can New Mexico break that incremental mold and provide a new model for ambitious reform?” That bill subsequently did pass one legislative committee and drew national advocacy before derailing. Since then, the political landscape around prison voting has changed significantly—with an endorsement from U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, similar bills introduced in about 10 states, and historic success in Washington, D.C., last year.

Qualified immunity

New Mexico could become just the third state to adopt a law targeting qualified immunity for police officers in state court. (Qualified immunity is the legal doctrine that often shields police departments from civil lawsuits after misconduct by officers.) Colorado became the first state to do so last year; Connecticut significantly narrowed qualified immunity but left in caveats.

The state House adopted a bill last week that would lift the qualified immunity defense when people bring lawsuits for wrongdoing against law enforcement. Jacob Sullum reviewed the bill’s details in Reason last week, noting that it goes further than the two other states’ laws in clarifying that individual police officers (as opposed to local governments and police departments) would not be personally liable. “Even without such legal requirements, police officers almost never have to pay a dime for their misconduct, since their employers routinely indemnify them,” Sullum writes. “This issue is therefore mostly a red herring in the debate about qualified immunity.”

Virginia: Abolition of the death penalty could come any moment now. Will other states follow suit?

The finish line is near for the Virginia legislation abolishing the death penalty, which this newsletter has tracked closely throughout the year. This week, both chambers passed the final version of the legislation, as was expected since they each adopted previous versions in early February. The latest votes send the bills to Governor Ralph Northam, a Democrat.

The governor has indicated he will sign the reform, and he could do so any day now. Our analysis of this death penalty law will appear on this page as soon as the law is signed.

Virginia’s legislative session is now in its final stretch, and lawmakers face other major decisions on issues that include felony disenfranchisement and mandatory minimum sentences. (See last week’s newsletter for more details.)

Will other states follow suit and abolish the death penalty as well in coming months? The Nevada Independent and City Beat report on the possibility in Nevada and Ohio, respectively. But prosecutors’ opposition looms large in both states. In Nevada, Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro, who works as a prosecutor when the legislature is not in session, has not indicated whether she would bring such a bill to the floor.

Texas: A new federal ruling protests race discrimination in jury selection, yet again

Prosecutors are barred from excluding Black people from juries because of their race, but in practice they have tremendous leeway to strike them from the jury pool with almost no accountability or recourse. A few states have adopted regulations to constrain racism in jury selection, including California in 2020, but even those regulations will only matter if courts are willing to enforce them.

A ruling handed down by the Fifth Circuit this month serves as a reminder that courts are typically complicit in enabling and justifying racist jury selection processes. A three-judge panel denied relief to a Black man who was sentenced to death after prosecutors tried to strike all people of color from the jury pool using a spreadsheet that highlighted potential jurors who were Black.

Kyle Barry writes in the Political Report on this new ruling and what it reveals about obstacles to fair trials.