Police Unions Fight To Rescind Parole For Former Black Panther

In April 2018, Herman Bell was paroled after spending 45 years in prison in a case involving the shooting deaths of two police officers. Now, New York police unions and the widow of one of the slain officers are challenging the decision in court.

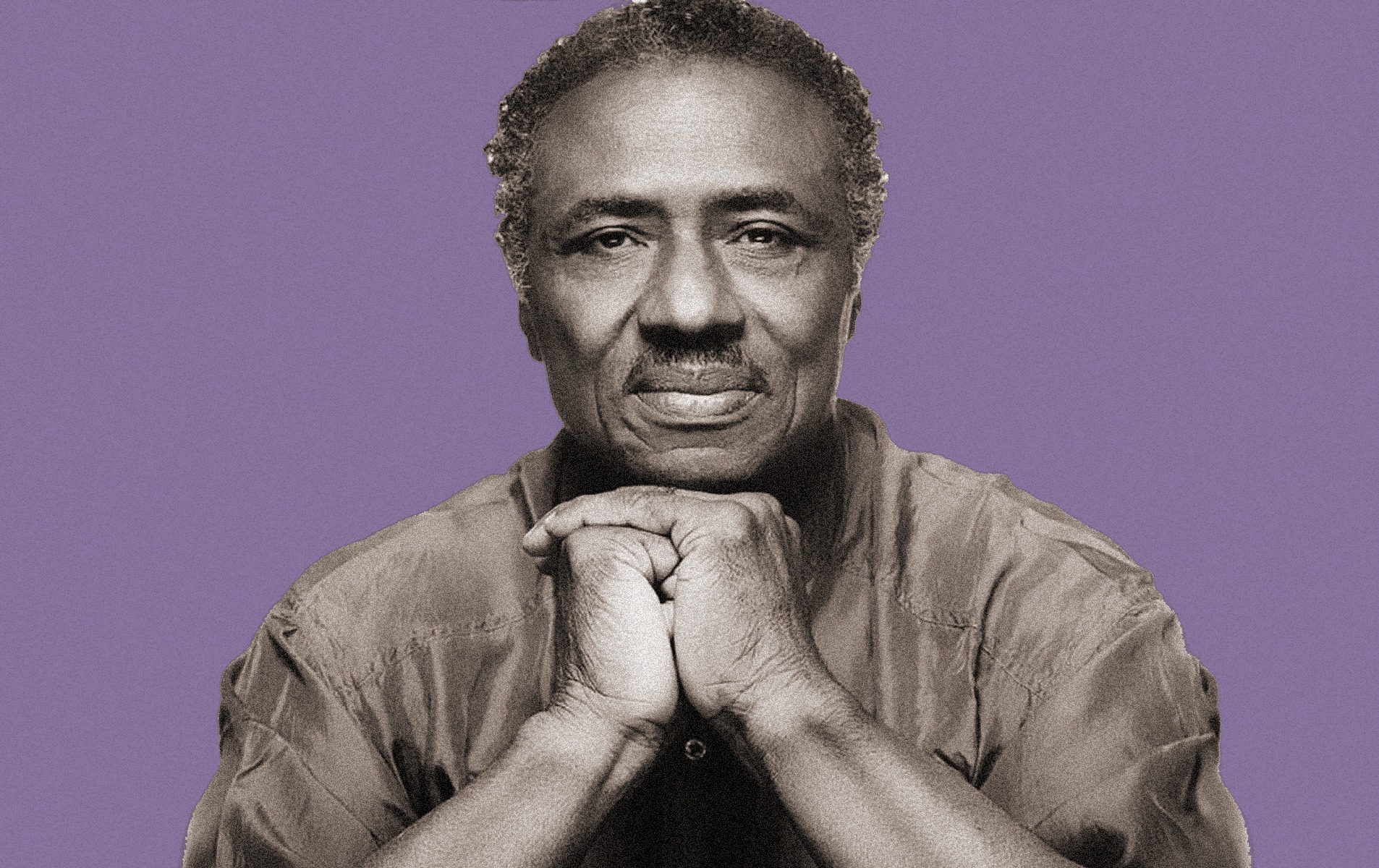

On April 27, 2018, 70-year-old Herman Bell was freed after spending 45 years in a New York state prison. The former Black Panther was convicted in the 1971 shooting deaths of two police officers and sentenced to 25 years to life. At a Board of Parole hearing just before Bell’s release, two of the three parole commissioners voted to grant him parole. It was Bell’s eighth hearing, and the commissioners cited his age, near-perfect prison record, college degrees, wide network of supporters as well as a letter of support from the son of one of the slain officers.

The Police Benevolent Association (PBA), which was then the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, blasted the board’s decision. “The parole board has lost their goddamn humanity to think that a murderer should walk their streets,” said PBA president Patrick Lynch. The union has a page on its website called “Keep Cop Killers in Jail,” and its criticism of the parole board was echoed by the NYPD commissioner, Governor Andrew Cuomo, and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Diane Piagentini, whose husband Joseph Piagentini was one of the slain officers, filed a request for judicial review of the parole decision. In her request, called an Article 78, Piagentini argued that because she’s entitled to be heard by the parole board as a victim, she must “have standing to challenge any subsequent decision by the Parole Board that is contrary to her position.” An acting New York State Supreme Court judge ruled against Piagentini, writing that the board followed protocol and that Piagentini had no legal standing to challenge its decision.

Piagentini and the PBA, whose attorneys represent her, have not given up on their efforts. They are seeking to rescind Bell’s parole and push the board for a new hearing with different commissioners. On Sept. 29, 2018, Piagentini filed an appeal, arguing that she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder because of her husband’s death and therefore should have legal standing to challenge the board’s decision, which she called “irrationality bordering on impropriety.”

Piagentini’s litigation raises foundational questions about the role victims play in the criminal legal system. How much influence should they have throughout the process? Should they be allowed to sue if they disagree with the decision of a parole board? Should their wishes—and desire for perpetual punishment—supersede a sentence imposed by the courts?

On Jan. 4, over 20 legal and advocacy organizations, including The Sentencing Project and The Legal Aid Society, filed an amicus brief in support of Bell and directly addressed those questions. “What Petitioner here seeks would interfere with the criminal justice process,” its authors wrote, referring to Piagentini. “She seeks standing to challenge a parole board determination. Petitioner’s private wishes cannot supplant the myriad interests the Board of Parole is charged with considering, including the public interest. All the concerns raised by judges and scholars regarding victim participation—the risk of decisions tainted by emotion and subjectivity, the risk of injecting bias, and the risk of considering inappropriate factors—apply in the context of a Board of Parole hearing, which is supposed to focus on many factors, only one of which pertains to the victim.”

Parole board “should not be a tool of prosecutors or police.”

It’s not the first time that a police union has attempted to stop a person convicted in the murder of an officer from being paroled. In 2003, the New York State Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) filed an Article 78 seeking to annul and reverse parole for Kathy Boudin who was sentenced to 20 years to life in the Oct. 20, 1981, robbery of a Brinks Corporation armored truck in which a guard was shot and killed. The state Supreme Court ruled against the FOP, stating that the FOP had no standing in the matter and that “while a relative of a crime victim may be more emotionally affected by the crime than a member of the general public, that increased emotional effect is not sufficient to confer standing.”

In 2018, the Police Benevolent Association of New York State Troopers filed an Article 78 challenging the parole board’s decision to release John E. Ruzas, sentenced to 25 years to life for the fatal shooting of a state trooper during an armed robbery in 1974. In the fall of 2017, Ruzas was granted parole at his twelfth hearing; by then, he had spent 44 years in prison. The state Supreme Court ruled against the association, stating, “While the Court acknowledges that petitioner’s members may experience heightened feelings of vulnerability when a fellow police officer is murdered in the line of duty, this emotional response, standing alone, is insufficient to give rise to an ‘injury in fact’ that would confer individual standing upon those officers to challenge a determination granting parole release to an inmate.”

In the amicus brief for Bell, its authors argue that although the victim’s voice is important, it should not be the sole consideration in the parole process, which must also consider a person’s efforts at rehabilitation since incarceration. In addition, victims are not a monolith, as demonstrated by Waverly Jones Jr., the son of one of the slain officers, who supported Bell’s release. Continuing to incarcerate Bell, Jones said, after he “has been in prison for over 30 years and hasn’t gotten into so much as an argument” would “only be for revenge.” The authors of the brief also noted that “Crime Survivors Speak,” a 2016 report by the Alliance on Safety and Justice, found that 60 percent of victims preferred increased spending on prevention and rehabilitation instead of long prison sentences. According to the brief, Piagentini and the PBA’s “suit attempts to usurp the lawful function of the Board of Parole and impose her private wish that the individual convicted of killing her husband remain imprisoned forever.”

In their Jan. 18 response to the amicus brief, PBA attorneys argued that Bell’s “targeted assassination of her [Piagentini’s] husband caused a lifetime of suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” and that by paroling Bell, the parole board is “profoundly exacerbating” her trauma.

“The PBA’s continuous attempts to disturb the Parole Board’s decisions are self-serving,” said Jose Saldana, the director of Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP), one of the organizations that signed the brief. Saldana spent 38 years in prison and was denied parole four times before being released in January 2018. “They do not serve the interests or sentiments of the Black and Latinx communities. They promote the notion that a police officer’s life has greater value than the lives of the hundreds of young Black and Latinx teenagers murdered every year.”

Laura Whitehorn, who spent 14 years in federal prison and now organizes with RAPP, noted that although Governor Cuomo disagreed with the parole board’s decision to release Bell, he still defended the commissioners’ decision and its independence. “The parole board should be an independent body,” Whitehorn said. “It should not be a tool of prosecutors or police.”