Police Respond To Accountability By Threatening A Slowdown

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. Yesterday seemed by all accounts a good day for police accountability. Scholars recently revealed that police violence is a leading cause of death for Black men, but […]

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

Yesterday seemed by all accounts a good day for police accountability. Scholars recently revealed that police violence is a leading cause of death for Black men, but it looks like the near-impunity that cops enjoy is shrinking, a little. Yesterday, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill prompted by killings of unarmed Black men that says police are allowed to kill civilians only as a “necessary” response to a threat—not merely an “objectively reasonable” response. Also yesterday, NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill fired the officer who killed Eric Garner in 2014 by putting him in a chokehold. These seem like steps in the right direction, and they are. Indeed, when signing the California bill, Newsom said, somewhat aspirationally, “As California goes, so goes the rest of the United States of America. And we are doing something today that stretches the boundaries of possibility and sends a message to people all across this country, that they can do more.”

But a message might be the greatest impact these actions have, and it’s unclear how strong the messages are anyway. “The whole debate boils down to two words: ‘necessary’ and ‘reasonable,’” Ben Adler of Capital Public Radio reports. “Right now, deadly force is justified if a reasonable officer would have acted similarly in that situation. So in other words, what a typical officer would have done based on his or her training. When the law takes effect in January, that standard will change to when the officer reasonably believes deadly force is necessary.” Adler also noted that the law does not provide a specific and complete definition of “necessary,” which will leave interpretation up to the courts. “The deleted language said officers could open fire when there is ‘no reasonable alternative,’” reports Don Thompson for the Associated Press.

“The amended measure also makes clear that officers are not required to retreat or back down in the face of a suspect’s resistance and officers don’t lose their right to self-defense if they use ‘objectively reasonable force,’” Thompson writes. “Amendments also strip out a specific requirement that officers try to de-escalate confrontations before using deadly force,” according to Peter Bibring, police practices director for the ACLU of California, which proposed the bill and negotiated the changes. “The courts can still consider whether officers needlessly escalated a situation or failed to use de-escalation tactics that could have avoided a shooting,” he said. Even in its current form, the ACLU considers the law to have the strongest language of any in the U.S.

Others disagree. “This is so watered down,” said Ed Obayashi, a use-of-force consultant to law enforcement agencies and a Plumas County, California, deputy sheriff. “The language is virtually legally synonymous with current constitutional standards for use of force. It really is a distinction without a legal difference.”

And law enforcement’s response, too, has been mixed. “There is hardly a dangerous encounter imaginable in which there wouldn’t be some conceivable way the officer may have been able to avoid using deadly force, including avoiding the confrontation entirely,” the president of the Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund wrote in an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle. “Unfortunately, that is what the likely result will be in California. Officers will tend to avoid circumstances in which deadly force is a possibility. They will very rationally act to protect their lives and careers—simply by avoiding dangerous encounters.”

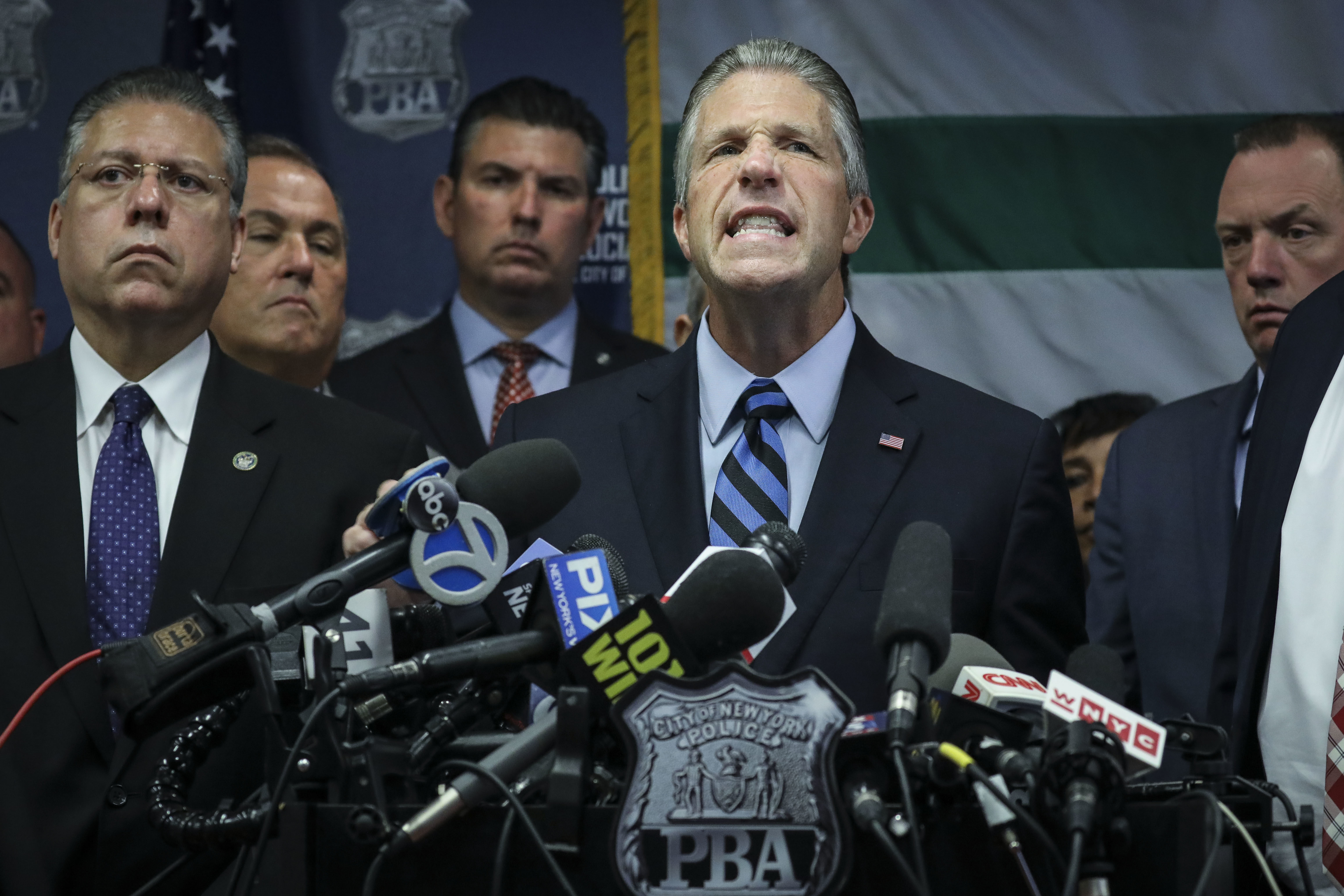

This is basically a toned-down version of the sentiment expressed by the New York City’s largest police union to Daniel Pantaleo’s firing. In front of an upside down NYPD flag, to signify that the department was “in distress,” Police Benevolent Association president Pat Lynch said, “We are urging all New York City police officers to proceed with the utmost caution in this new reality, in which they may be deemed ‘reckless’ just for doing their job. We will uphold our oath, but we cannot and will not do so by needlessly jeopardizing our careers or our personal safety.”

If police are going to arm themselves to the teeth with military equipment unknown to most world armies, and throw a fit when asked to comply with minimal standards when dealing with unarmed civilians, and then refuse to work if it means taking any career or personal risks, it seems like they should lose the right to remind the public at every opportunity that they have such dangerous jobs.

But the union response isn’t all too surprising given that the police commissioner himself went out of his way to say that he identified and sympathized most not with the unarmed man who was killed, but rather with his killer. The “us vs. them” mentality couldn’t have been clearer, and couldn’t have more effectively undermined the idea that a few bad apples are responsible for all of the problems in law enforcement. “I served for nearly 34 years as a uniformed New York City cop before becoming police commissioner,” O’Neill said. “I can tell you that, had I been in Officer Pantaleo’s situation, I may have made similar mistakes.” He added, “Every member of law enforcement in this country that works and keeps this country safe and this city safe looked at that and said, ‘That could possibly be me.’”