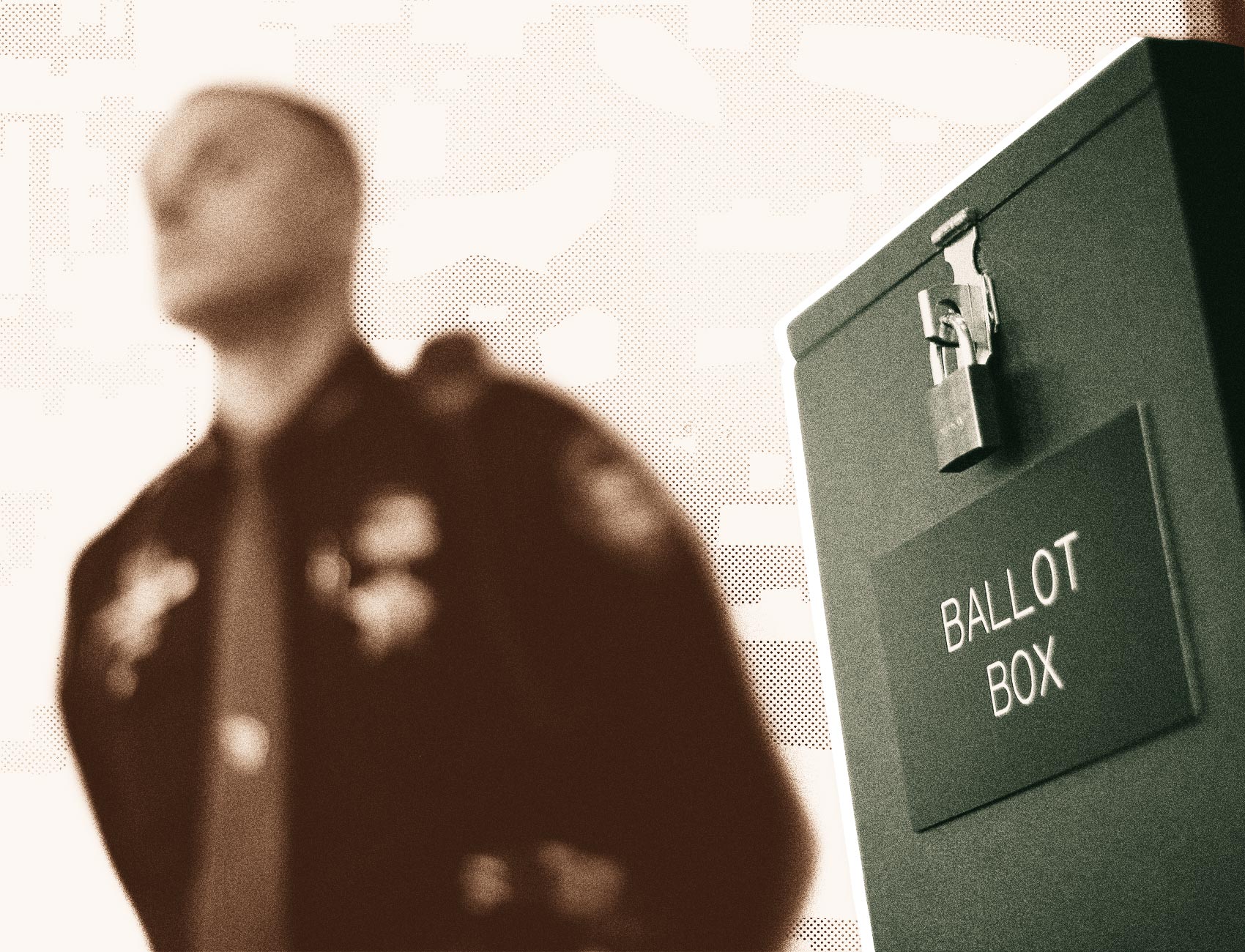

Police at Polling Places Could Intimidate Voters This November, Advocates Warn

This year’s presidential contest will be the first since a federal judge lifted a decades-old consent decree barring the Republican National Committee from engaging in “ballot security,” or voter intimidation at the polls.

With police violence and the pandemic occupying the national spotlight, the November election is bound to look like no other in U.S. history. The closure of polling places during the primaries has already led to voter suppression. At the same time, voting rights advocates are warning that police could be stationed at polls that remain open in November, leading to voter intimidation.

For the first time in almost four decades, the U.S. will hold a presidential election without a consent decree barring the Republican National Committee from engaging in “ballot security,” or voter intimidation at the polls. With this new freedom, the Republican Party has formulated a plan to recruit up to 50,000 volunteers in 15 key states to watch polling places and dispute “suspicious” ballots—and some groups are pushing to assign off-duty or retired police officers to monitor polling locations, especially in nonwhite communities.

“Whether it’s an armed police officer patrolling a polling place or just having a police car with lights blaring in front of a polling place, all can serve as a form of voter intimidation and certainly can have a chilling effect, particularly in Black and brown communities,” said Gilda Daniels, litigation director for the Advancement Project and author of “Uncounted: The Crisis of Voter Suppression in America.”

“If we add what’s happening in our society today in regards to the relationship between police officers and people of color, having a police presence at a polling place could rise to the level of voter intimidation, even more so than in previous years,” she said.

Jon Greenbaum, chief counsel and senior deputy director for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, agreed. “If the experience of you or your family members with law enforcement has been really bad, you’re not going to want to see a police officer at the polls,” he said. “Their presence can have the effect of turning people away.”

True the Vote, a conservative vote-monitoring organization, has begun recruiting off-duty police officers and veterans to serve as poll monitors, according to audio recordings of a conservative strategy event in February obtained by The Intercept and Documented.

Conservatives at the event expressed enthusiasm for using law enforcement to watch polling places. “Do you want to go into an inner city precinct or a tribal precinct and be the Republican there to oversee things? I mean, that is not a comfortable place to be, and that is where the fraud happens,” said Trent England, executive director of conservative think tank Oklahoma Council for Public Affairs, according to The Intercept. “We have to find people.”

Conservative lawmakers have also pushed to have police stationed at the polls in November. In January, Republican Arizona Representative Jay Lawrence introduced a bill to the state legislature that would require every polling place in the state to have a police officer posted at or inside the polls.

“There are individuals in our society whose anger is so thorough, so extreme, that they will do anything they can,” Lawrence said in January, describing people he envisions disrupting voting on Election Day. He added that he doubts the state will offer to pay the steep costs associated with assigning such officers to every polling place.

There is a long history in the United States of police officers having a presence at polling places as a way to intimidate voters. Before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, police officers notoriously shut down voter registration efforts in certain jurisdictions in the South. Voting rights advocates have warned that such a police presence this year, especially targeted in communities who fear law enforcement violence, could bring the U.S. back to the Jim Crow-era and could diminish voter turnout in a critical election year.

A judge originally ordered the consent decree as part of litigation following the 1981 New Jersey gubernatorial election, when the RNC recruited armed, off-duty police officers to wear “Ballot Security Task Force” arm bands and intimidate African American and Latinx voters by threatening arrest and fines of $1,000 for improper voting.

In 2016, three years after the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement, Macon-Bibb County, Georgia, announced plans to move a polling place to the sheriff’s office. “Using the Sheriff’s office as a polling place can be intimidating, especially considering the history of violence by local law enforcement at the polls during the Jim Crow era,” the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights wrote in a 2018 report on nonwhite voting access. In order to stop the move, local advocates successfully collected signatures from 20 percent of active, registered voters in the county.

Also in 2016, the Advancement Project and local civil rights groups spoke out about a directive in Greene County, Missouri, to place armed sheriff’s deputies at polling sites in Springfield, Missouri, during the November presidential election. Police should only be at the polls, the groups said, where a specific and legitimate law enforcement need justifies that presence.

The effort to block the officers ultimately failed, although the clerk agreed to reduce any potential intimidating factors by having the officers wear plain clothes instead of uniforms and have their weapons and badges concealed.

In 2018, a federal judge refused to extend the consent decree, paving the way for the national Republican Party to mount efforts to prevent alleged voter fraud. Since that ruling, the Republican Party and conservative operatives have formulated ways to take advantage of the new freedom. President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has spread false information about mail-in voting and has perpetuated conspiracies about voter fraud.

Lauren Groh-Wargo, CEO of voting rights organization Fair Fight Action, said a police presence might act as a deterrent for someone who fears what an interaction with law enforcement would mean for their future.

A police officer at the polls might make someone think, “Oh wait a minute, if there’s police outside, are they going to ask if I’ve paid my child support? Are they going to harass me on other issues I may be having?” she said.

Groh-Wargo said she is also concerned about the potential presence of ICE officers at certain polling locations, who could scare away multigenerational or multi-immigrant status families who may bring noncitizens with them to the polling place, while only the citizens cast ballots.

She also said she’s worried about how the federal government might use the military and federal law enforcement on Election Day, given how President Trump used federal forces to violently clear protesters near the White House last month.

“When you see what Trump’s been willing to do with militarized police and the military in the uprisings in D.C., I think we should be prepared for that,” she said.