Police Killed Saheed Vassell in a Gentrifying Neighborhood. Did That Make a Difference?

Last week, the night after Saheed Vassell was shot and killed by the NYPD, a large crowd gathered for a vigil and a speak-out on the Brooklyn street corner where Vassell died. Several of the speakers asked rhetorically who called 911, summoning the police who shot him. As reporting in the New York Times showed, many of Vassell’s […]

Last week, the night after Saheed Vassell was shot and killed by the NYPD, a large crowd gathered for a vigil and a speak-out on the Brooklyn street corner where Vassell died. Several of the speakers asked rhetorically who called 911, summoning the police who shot him. As reporting in the New York Times showed, many of Vassell’s neighbors in Crown Heights were familiar with him. They knew he was harmless and that he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. So, was it newcomers to the neighborhood who called the police that day?

The three 911 call transcripts do not provide many clues, and the NYPD does not release identifying information about 911 callers. One caller sounds like a laundromat employee or owner. While it is hard to know in this case if gentrifiers were among the three callers, the aggregate trend is clearer: Calls to the NYPD are higher in gentrifying neighborhoods, and Vassell’s neighborhood was gentrifying.

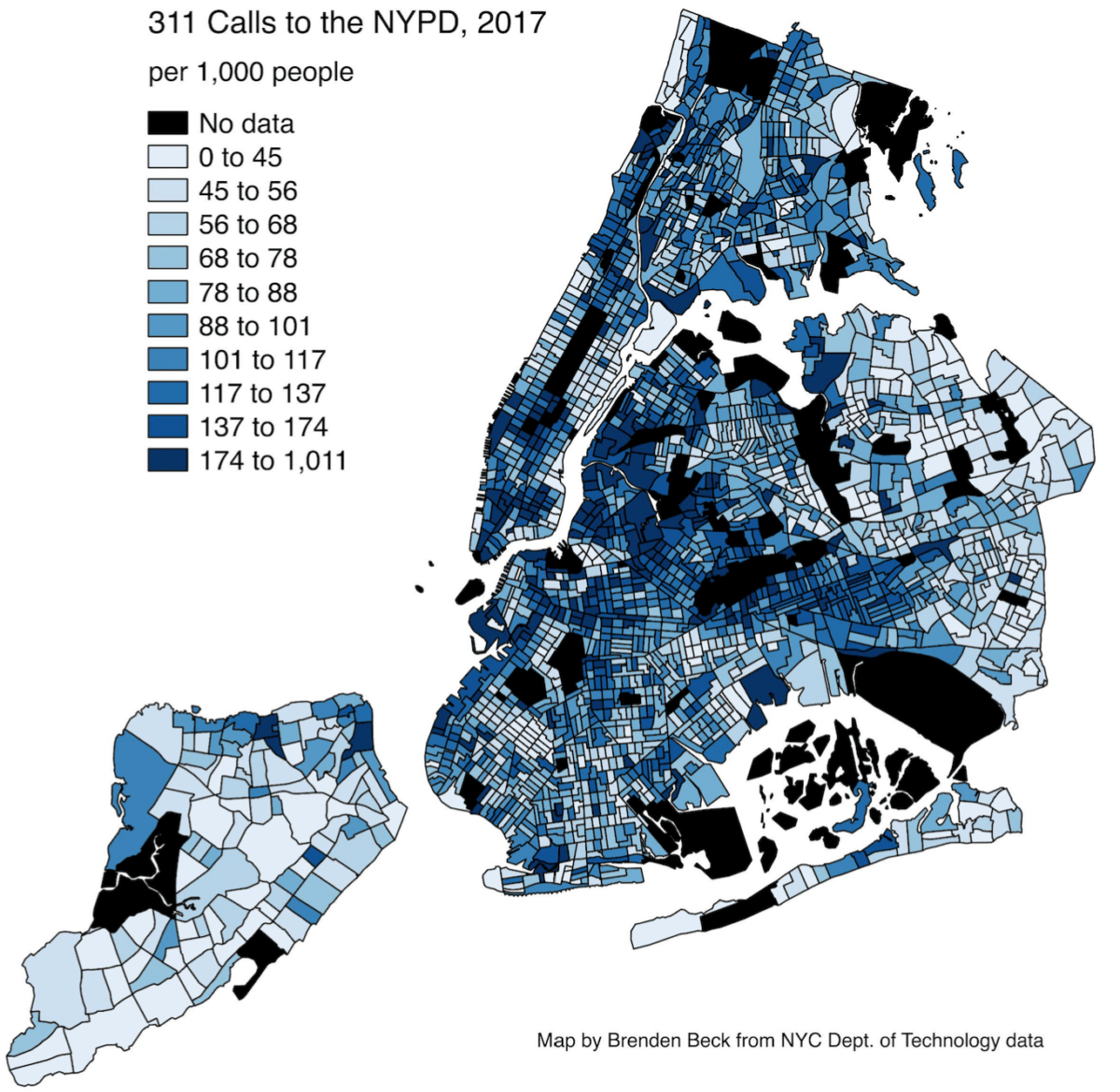

Requests for service provide one window into this trend. While New York City does not release data on emergency calls, it does release data on non-emergency calls to the NYPD made via 311. These include complaints about noise, drinking, drug activity, urinating in public, and illegal parking.

Last year, the NYPD received 319 non-emergency complaints from the typical neighborhood. The median gentrifying neighborhood, however, generated 386 complaints, and Saheed Vassell’s neighborhood generated 451. As with emergency call data, the identities of 311 callers are not known. But, as these numbers show, as more middle-class, credentialed, and white residents move into New York City’s formerly working-class areas, calls to the police increase.

Saheed Vassell’s Brooklyn neighborhood was, by any metric, gentrifying. A common definition of gentrification includes neighborhoods with below-median incomes in a given year and above-median growth in property values and residents with a bachelor’s degree in subsequent years. Vassell’s neighborhood meets these criteria — and then some. In 2009, the typical household there made less than half the city median income according to Census data. Seven years later, in 2016, real estate prices had gone up 30 percent, median monthly rent increased by $170, and the percent of residents with a B.A. rose over 55 percent. The racial composition also changed, with the white population growing from 9 percent to 14 percent of residents.

The map below shows the number of 311 complaints to the NYPD for New York’s 2,000 census tracts. While it is clear that gentrification is far from the only trend affecting call differences, some neighborhoods commonly understood to be gentrifying experienced high call volume. These included Long Island City, Greenpoint, Williamsburg, and Crown Heights. Wealthier, whiter, more stable neighborhoods experienced few calls, including most of Staten Island, the Upper West Side, the Upper East Side, and low-density Queens. The north shore of Staten Island, where Eric Garner died from an NYPD chokehold in 2017, is another gentrifying neighborhood that experienced high numbers of complaints to the NYPD.

While gentrification often includes changes in a neighborhood’s class composition and housing prices, ethnoracial differences can prove the most salient. A 2016 study by Joscha Legewie and Merlin Schaeffer found 311 complaints increased in the “fuzzy boundary” areas between racially homogeneous neighborhoods. These “transitional areas” are often where gentrification is most acute.

In the context of neighborhood change, conflicts can arise between newer and long-term residents. The groups might disagree about norms for behavior in public space, about appropriate noise levels or parking etiquette. Racial bias by new, white residents might make them fearful of their Black and Latino neighbors. And new residents, no matter their identity, will be less likely to know their neighbors. Any neighborhood experiencing a frequent churn of residents is likely to be a more anonymous neighborhood.

Besides generating more calls to police, does gentrification affect police behavior? A 2017 study by Ayobami Laniyonu found a strong association between gentrification and increased police stops. In an unpublished study, I found police made, on average, more pedestrian stops of Black and Latino people and fewer stops of white people in New York City when a neighborhood’s white population increased. Instances of police killing unarmed Black people are the tip of an iceberg that includes frequent, lower-level police interactions.

The public conversation around gentrification includes discussion of how it can raise housing prices, displace long-time residents, and reshape neighborhood retail options. In addition to rent hikes, evictions, and coffee shops, gentrification might bring more police activity. And as Saheed Vassell’s death shows, the consequences can be severe.