Police Accountability and Public Defender Groups Demand Transparency on NYPD Gang Policing

Since its initiation in 2013, the NYPD’s gang policing program has operated with little outside scrutiny. Based on evidence it has kept almost entirely hidden from public view, the police have targeted and surveilled entire social networks inside low-income communities, breaking down doors in pre-dawn military-style raids that have resulted in over 2,000 arrests in just the […]

Since its initiation in 2013, the NYPD’s gang policing program has operated with little outside scrutiny. Based on evidence it has kept almost entirely hidden from public view, the police have targeted and surveilled entire social networks inside low-income communities, breaking down doors in pre-dawn military-style raids that have resulted in over 2,000 arrests in just the past year and a half.

Instead of local district attorneys charging the young men and women arrested by the NYPD, most of the indictments are in the form of federal RICO charges, which tie alleged members of the “gang” or “group” to the most serious offense any member has committed. Because of the severity of the federal sentences faced by many defendants, the overwhelming majority take plea deals, meaning that the NYPD and federal prosecutors often need not divulge evidence they have against these alleged “gangs.”

But some level of transparency may soon come to the NYPD’s gang policing program. In a letter sent February 5, a coalition of more than 25 police accountability and public defender groups called on the City Council to hold hearings about the constitutionality of the program, which uses a secret database of “gang members” to target communities of color and, in particular, those who live in public housing. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (LDF) and the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) sent a separate letter on the same day, urging the council to look into whether individuals can challenge their inclusion on a gang database, and whether this violates their “due process” rights.

“Right now, the program is being conducted with zero oversight,” Marne Lenox, an attorney for the Legal Defense Fund told The Appeal. There are “zero safety precautions to ensure that folks aren’t erroneously in the database, and it exposes the NYPD to zero accountability for their policing actions.”

The letter from the police accountability and public defender groups is addressed to Council Member Donovan Richards, who chairs the council’s Committee on Public Safety.

“We believe that, like the widespread stop-and-frisk strategies that the NYPD relied upon in the recent past, gang designations are likely to be overinclusive and inaccurate,” the letter says. “Unlike the stop-and-frisk records, gang databases are secret, do not require even a suspicion of criminality, and are often not subject to judicial review. Indeed, the NYPD has not publicly disclosed whether there is any way to challenge gang designations, or whether people may ‘age out’ of their designation, for example, as they mature and go away to college.”

CUNY law professor Babe Howell has researched the NYPD’s gang policing program for years, and has traced how the NYPD turned to large-scale gang raids shortly after a federal judge declared its stop-and-frisk program unconstitutional.

The advocacy and legal groups also point out that the NYPD’s designation of immigrants as potential gang members could make them targets of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) through information sharing between the NYPD and ICE, even though New York City bills itself as a “sanctuary city,” in which that is, for the most part, not supposed to happen.

In Chicago, which is also a “sanctuary city,” a gang database error led to one man’s violent arrest by ICE, which may have accessed the information through the National Crime Information Center. New York City’s detainer lawprohibits this type of information-sharing, but advocates say that without knowing exactly who is on the database and who has access to it, holding the NYPD accountable is nearly impossible.

The letter from LDF and CCR, which is in support of the letter sent to Richards, questions the constitutionality of the program.

“The geographic targets of the raids, coupled with the resulting racially disproportionate arrests and the NYPD’s past conduct, warrants public hearings to determine whether the City is engaged in unconstitutional actions,” the letter reads.

Ritchie Torres, who chairs the council’s new Committee on Oversight and Investigations, told The Appeal that he’s open to holding joint hearings with Richards’s public safety committee on the NYPD’s use of gang policing.

“We’re seeing more gang takedowns than ever before, on a scale we’ve never seen before,” Torres said. “These takedowns have been so large that it leads to questions of whether we’re targeting the drivers of violence or are we casting the net too wide? If we’re casting the net too wide, then we’re undermining the end goal of criminal justice reform and of curbing over-criminaliztion.”

In previous City Council oversight hearings, the NYPD has been less than forthcoming about its surveillance and policing practices. Torres doesn’t think this time would be very different.

“The NYPD in my experience is almost never forthcoming,” said Torres. “It would be wishful thinking that they would. There will most likely be intense resistance to oversight.”

Councilman Richards declined to comment for this story.

Similar calls for transparency are also being made in Chicago, where activists and researchers have recently launched a reporting project to shed light on its gang database, in which 95 percent of the 65,000 individuals included are Black or Latino.

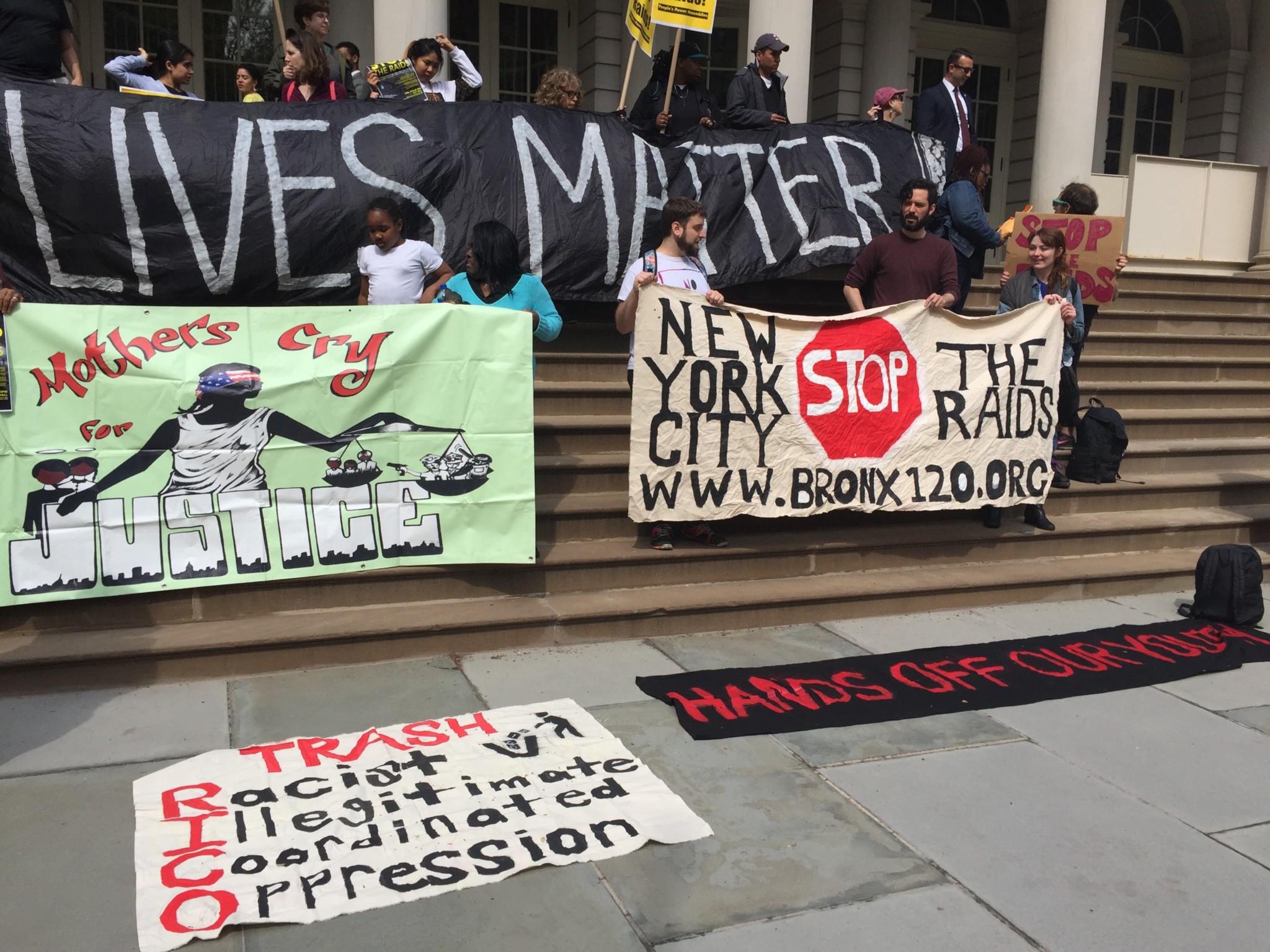

On February 7, the coalition of groups calling for more transparency into the NYPD’s gang policing program gathered on the steps of City Hall to demand that the city council begin oversight hearings. The LDF’s Lenox insists this is just one way the groups will attempt to bring transparency to the NYPD’s use of gang policing and further steps may be necessary to force the police to release more information.

Also that day, Legal Aid announced a new initative, dubbed the “Do It Yourself FOIL Campaign,” which will encourage and help people who think they might be on the NYPD’s gang database to use the Freedom of Information Law in the hope of shedding even more light on the secret database.