As Protests Grow, Judges Mull Reopening Phoenix Police Shooting Lawsuit

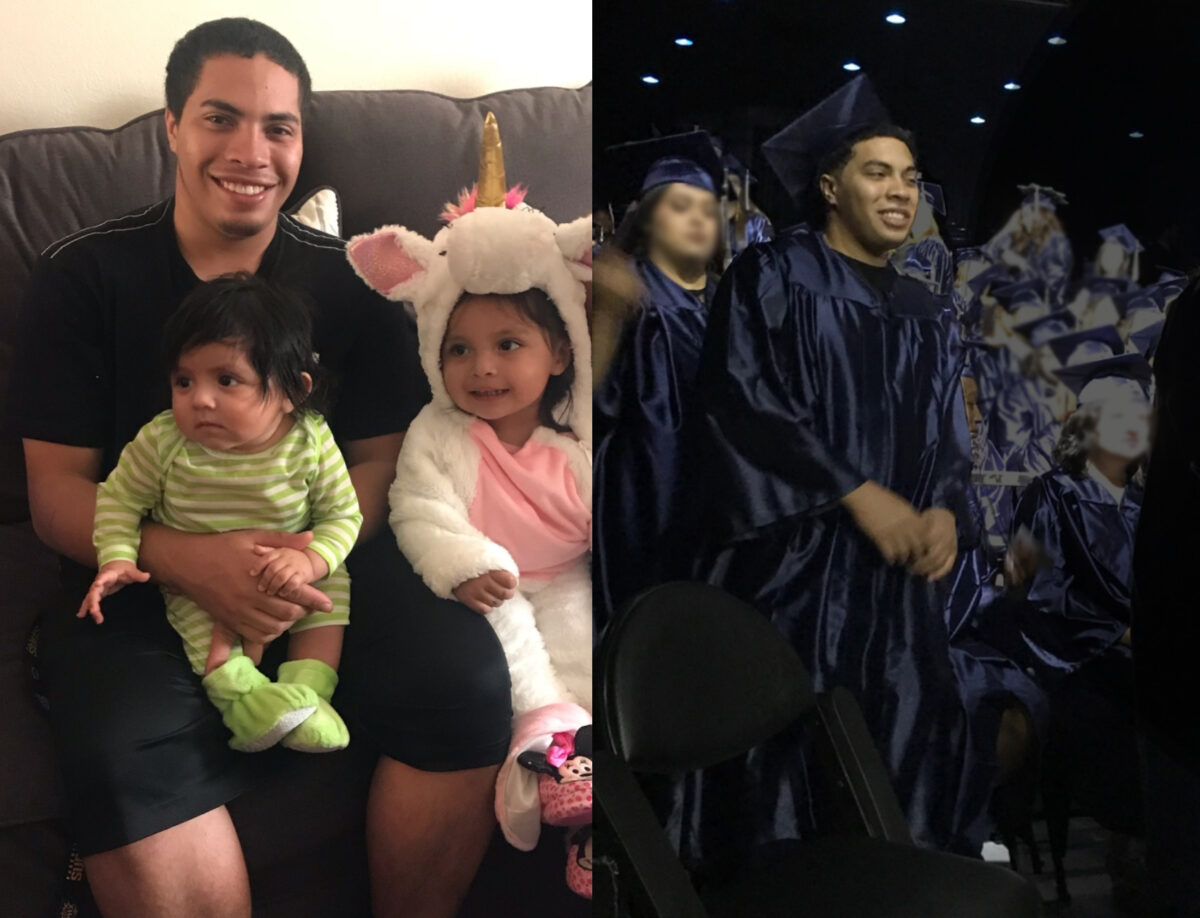

Phoenix Police Department Officer Kristopher Bertz shot and killed 19-year-old Jacob Harris in 2019. Now, community members are rallying as Harris’s father Roland appeals a wrongful death lawsuit.

On a sunny September morning in Phoenix, about a dozen people stood outside a federal courthouse holding signs that read, “Justice for Jacob Harris,” “Free the Phoenix Three,” and “Fire officer Kristopher Bertz,” the police officer who killed Jacob Harris. The group had gathered to support Jacob’s father, Roland Harris, during the latest court battle in his years-long fight to hold the Phoenix Police Department and the officer who killed his child accountable.

The protesters also demanded the release of Jacob’s friends—Jeremiah Triplett, Sariah Busani, and Johnny Reed—who were with Jacob on the night police killed Jacob. A judge sentenced all three to decades in prison for Jacob’s death using Arizona’s felony murder law—even though none of them killed Jacob.

“The day that the Phoenix Police Department murdered Jacob was the worst day of all of our lives,” Theresa Greene, Triplett’s mother, wrote in a letter read by Refilwe Gqajela of the Anti Police-Terror Project. “We ask you to stand with us in demanding reparations with the release of the Phoenix 3, the return of Jacob’s personal items to his family, and the indictment of the officers responsible for the torture and murder of Jacob Harris. Stop letting them get away with killing and incarcerating our children to take the blame for the crimes they commit themselves.”

On Jan. 11, 2019, Bertz shot 19-year-old Jacob Harris in the back as the teen ran away, killing him. Roland Harris then filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city of Phoenix and the officer who shot his son. A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit last year. Harris appealed. The case then went before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals on September 13, where supporters of Jacob Harris packed the court.

During that hearing, Steve Benedetto, an attorney representing the Harris family, argued that the case should be reopened for three reasons. First, Benedetto said the lower court erred when it ruled that Harris’s family could not amend the original complaint to address deficiencies in the complaint written by the family’s previous lawyer. Second, Benedetto argued that the lower court erroneously dismissed the wrongful death claims against the city of Phoenix. Third, Benedetto suggested that a jury should determine if an officer could reasonably believe deadly force was necessary to stop Jacob from fleeing.

“Jacob Harris was 19 years old when a weapon of war—a stun grenade—went off feet from him in his vehicle,” Benedetto told the court. “He ran, and three seconds later he’d been shot in the back by an AR-15 multiple times and laid on the ground bleeding out. Three rulings of the District Court deprived his family—his survivors—of the ability to present that case to a jury.”

Christina Retts, an attorney for the city of Phoenix, disagreed with Benedetto’s assertions and said Arizona state law justifies the officer’s use of deadly force against Jacob, who she said was a “fleeing felon” who made a choice to run away from police.

During the arguments, members of the three-judge panel frequently interrupted the attorneys to ask probing questions. Judges Ronald Gould, Andrew Hurwitz, and Patrick Bumatay—appointed by Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, respectively—will rule sometime later this year.

“This is an important case,” Judge Hurwitz said during the proceedings.

The judges will either affirm the lower court’s ruling or reverse it and send it back to the same judge who originally dismissed the lawsuit, reopening the case.

“The thing that the City of Phoenix doesn’t realize is that even if the civil case doesn’t go through, I’m not going to stop,” Harris said outside the courthouse on September 13. “If you want me to back off, fire the officers who murdered my son. Give my son the justice he deserves.”

On Jan. 10, 2019, Phoenix police officers surveilled a group of teenagers they believed were involved in a string of armed robberies at fast food restaurants and convenience stores. Police spent the 12 hours before Jacob’s death watching him and his friends from unmarked vehicles and a surveillance aircraft.

Kristopher Bertz, the officer who shot and killed Jacob, later said during a deposition that police officers chose to “allow a robbery to happen,” because police didn’t think they had enough probable cause to make an arrest.

So, on January 11, when Jacob’s friends crawled through the drive-thru window of a burger restaurant and pointed an airsoft gun at the employees inside, members of multiple law enforcement agencies—including the Phoenix Police Department (PPD) and the Goodyear Police Department—sat back and watched. Two minutes later, Harris, Triplett, and Reed, who was 14 at the time, left the restaurant and got into their friend’s vehicle.

Police followed the group for nearly ten minutes without using sirens or attempting to pull them over, even stopping behind the teens at a red light. Then, a Phoenix police officer deployed a heavy-duty nylon tether device called The Grappler to latch on to the car’s axle and jerk the car to a stop.

Officer Bertz threw a flashbang while several unmarked police cars closed in on the getaway vehicle. In the chaos, Jacob opened the rear passenger door and ran away from the car. Within seconds, Bertz shot at Jacob seven times with an AR-15-style assault rifle, piercing his heart, lungs, and intestines. Other officers fired rubber bullets at Jacob’s face and backside as he lay crumpled on the ground. Then they sicced a dog on him. Jacob died about an hour later.

Attorneys for Roland Harris said during the hearing that the day-long lead-up to the shooting is crucial because it shows that Bertz’s choice to shoot Jacob was not a split-second decision, but rather, “a reasonably foreseeable outcome of the gross negligence of the plan itself.”

Records show that officers discussed the plan to disable the vehicle and throw a flashbang over the police radio minutes before killing Jacob. Officers also discussed the events of that evening in text messages shared on the encrypted messaging platform WhatsApp—but records of those conversations were deleted.

“This was a multi-hour operation during which a plan was agreed upon that they would execute this fairly high-risk plan to disable this vehicle by surprise,” Benedetto said. “Our argument is that the fatal shooting that happened afterward is a reasonably foreseeable outcome of that negligent plan.”

To prove the city was negligent, plaintiffs must prove that officers had not just the intention to use excessive force, but the tendency to do so. Retts, representing Bertz and the city of Phoenix, said Benedetto’s arguments failed to meet that standard, in part because this was the first time Phoenix police officers had used a grappler.

But the Phoenix Police Department is currently being investigated by the Department of Justice for its use of deadly force and civil rights violations. Bertz previously shot and killed someone in 2017, two years before killing Jacob. David Norman—the officer who used the grappler and who also shot at Jacob, but missed—had shot at three people prior to the 2019 incident, one in 2014 and two in 2018.

Retts argued that ultimately, Arizona state statutes governing the use of deadly force allowed Bertz to kill Jacob. Specifically, the law states that police officers can use deadly force when the officer “reasonably believes that it is necessary” in order to make an arrest or prevent the escape of a person whom the officer “reasonably believes: has committed, attempted to commit, is committing, or is attempting to commit a felony involving the use of a deadly weapon” or “through past or present conduct of the person which is known by the peace officer that the person is likely to endanger human life or inflict serious bodily injury to another unless apprehended without delay.”

“We still have a fleeing felon,” Retts said. “The officers had reasonable belief that he would endanger the safety of the community based upon the 27-odd prior armed robberies.”

Harris’s family is also disputing whether Jacob actually had a gun on him when he fled from police—Roland Harris believes that his son was holding a cell phone, not a gun. Aerial surveillance footage shows an object dropping from Jacob’s hand when he is shot. Crime scene photos and police records reviewed by The Appeal did not clearly document the distance between where police say they found the gun and where Jacob’s body was. Of the eight officers who were present at the time of the shooting and provided official statements, only two—Norman and Bertz—said they saw Jacob holding a gun.

The 121-page police report also contains conflicting descriptions of where the gun was found in relation to Jacob: one officer described the gun as being “approximately three to four yards” from Jacob, while another said it was much closer, only “a couple of feet” from him.

The video shows an officer walking toward the object on the ground. The officer looks at it, walks further, as if looking for something else, then returns to the object. The video cuts off shortly after that. Benedetto noted in court that he never heard any deposition or testimony from that officer confirming he looked down and saw a firearm.

“What we have is a video showing something flying out of a hand,” Benedetto said. “And we don’t have a crime scene investigator. The person who was the crime scene investigator wasn’t made available.”

Harris’s attorneys repeatedly tried to depose the crime scene investigator—former homicide detective Jennifer DiPonzio. But Retts told the family that DiPonzio was unavailable because “she can hardly speak at all and is out-of-breath consistently” and was “medically incapable of being deposed.”

DiPonzio went on medical leave in 2021. She quietly retired the following year. Since then, local news outlet ABC15 reported that DiPonzio mishandled evidence in dozens of murder cases. If Harris’s appeal succeeds, his attorneys may have the opportunity to explore whether DiPonzio’s misconduct impacted the investigation of Jacob’s killing.

The judges noted that police saw Jacob carrying a firearm earlier in the day, as evidenced by a photo of him with what appears to be a black barrel coming out of his waistband.

Retts argued that Bertz had a reasonable belief that Jacob was armed at the time that he shot him, not only because of the photograph from earlier in the day, but also because officers had repeatedly photographed Jacob’s friends with another firearm that day—an Airsoft gun that only shot small plastic pellets.

When Roland Harris filed his lawsuit against the city of Phoenix in 2020, he was represented by a different lawyer: former Arizona Attorney General and current Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne. Horne, now 78 years old, has made many controversial decisions during his time in politics, including banning Mexican-American studies in Tucson schools.

Harris’s current attorneys say Horne made deficient pleadings in the complaint he filed in 2020. Benedetto argued that he should have been able to amend that complaint before the lawsuit was dismissed.

Retts argued that she notified Harris’s new counsel of the deficiencies multiple times throughout the proceedings, so they had ample opportunities to amend the complaint. The legal claim Harris’s attorneys later sought to include in the complaint involved a loss of consortium—a legal term that refers to the deprivation of the benefits of a family relationship, such as the love of a child, due to the actions of the defendant.

“Should the plaintiff really suffer because of those mistakes?” Hurwitz said. “It seems obvious that the survivors of the decedent lost consortium…Why shouldn’t a district judge—whether it’s a good cause standard or some other standard—allow them to amend their complaint and pursue that claim?”

Retts argued that even if the consortium claim was added to the complaint, it wouldn’t have changed the outcome of the lawsuit because Bertz’s actions were legal in Arizona.