Philadelphia Housing Authority Is Failing at Its Mission, Advocates Say

Although the agency has vacant properties, public housing has been out of reach for nearly a decade for many who need it.

In April, Brandon and several other people without homes sought refuge in an unused building owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority, a public agency that provides affordable housing opportunities to people in the city.

For weeks, the group fixed up the North Philadelphia property, which was falling into disrepair and had been vacant for some time. They moved in furniture and made the house their home.

But on May 13, Philadelphia police charged Brandon with felony burglary for being in the vacant home. They threw out everyone inside the house—including Brandon, his son, and his son’s pregnant girlfriend—and locked the doors, leaving their furniture and property inside. (Brandon requested that The Appeal not use his real name, as his charges are still pending.)

“At that moment, the house got boarded up and I got put out on the street with everyone else in the process of making a house a home,” Brandon said.

A day after his arrest, Brandon was released on unsecured bail, meaning he did not have to pay money but owes $100,000 if he fails to appear for court. Since his release, he has been living in a tent in an encampment with other unhoused people.

Should he ultimately get convicted of burglary for being in the home, Brandon would be barred from receiving housing from the housing authority for five years. In practice, however, it could be much longer.

According to advocates, the agency, also known as PHA, is not doing all it can to meet the needs of people without homes, leaving people like Brandon in desperate situations. Along with the more than 13,000 properties that PHA operates, it owns thousands more that are being left vacant or sold off to private developers rather than rehabilitated and used to house people in need in the city.

Meanwhile, on any given night in Philadelphia, nearly 6,000 people are considered homeless, and nearly 1,000 people are without shelter. Nearly 50,000 people are on PHA’s waiting list, which has been essentially closed since 2013, and the average wait time to be placed in many of its properties is around 13 years.

PHA has a roughly $400 million annual operating budget, and its CEO is making almost $300,000 a year, noted Jennifer Bennetch, an organizer with Occupy Philadelphia Housing Authority. “They owe everybody to do their job and provide this housing,” she said of the agency.

In fiscal year 2020 alone, the housing authority planned to dispose of more than 1,200 vacant properties, including more than 1,100 multi-bedroom homes in the city. And in June of last year, the agency brought in $8.4 million by auctioning off 144 vacant properties to private buyers.

Proceeds from the auction, and others like it, are supposed to be used to renovate other PHA properties. They are meant to be part of the authority’s long-term plan for its vacant public housing properties across the city as it faces what the agency describes as “inadequate federal funding,” which accounted for roughly 90 percent of its annual revenue in 2018.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development suspended millions in funding for PHA and placed the it under federal control after allegations of corruption and misuse of federal funds, including more than $500,000 to settle sexual harassment lawsuits levied against former executive director Carl Greene. Local control resumed in April 2013.

The authority has more than $1 billion in housing upgrade and renovation needs, according to its fiscal 2020 report. Yet, Bennetch pointed out, it spent $45 million on the construction of a new headquarters.

Bennetch and her group recently helped move 11 families into vacant, unused PHA buildings. She described the process as reclaiming the properties for their intended purpose. The families who move into the homes pay for utilities and have helped repair the properties because PHA failed to do so, Bennetch said.

“For them to say they can’t repair these buildings, we’ve moved 11 families now into homes over the winter, when everyone is out of work during [COVID-19], so we know that they have the money to repair these homes if they wanted to,” she said.

The agency did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment.

Moving the families into vacant homes is part of a larger movement among advocates in the city to bring attention to the issues facing unhoused people.

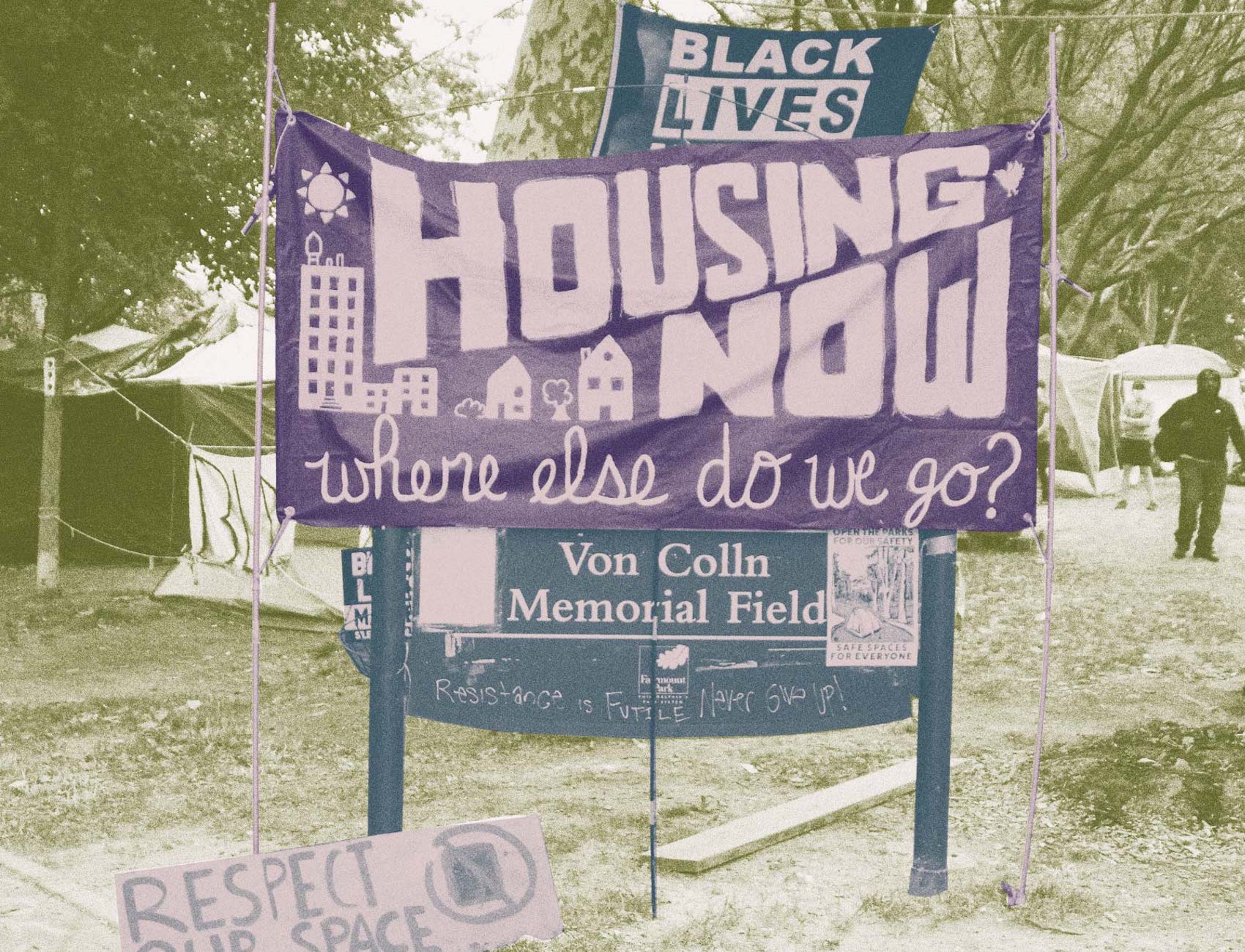

In June, advocates including Occupy Philadelphia Housing Authority and Philadelphia Housing Action set up the James Talib-Dean encampment at North 22nd Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. More than 100 people have joined the protest encampment since.

The city planned to evict the encampment on July 17 but backed down at the last minute and has been in talks with organizers since. (A similar encampment to protest the NYPD’s budget was set up in New York City outside City Hall before police cleared it out on July 22 and arrested some of protesters.)

Sterling Johnson, a spokesperson with Philadelphia Housing Action, told The Appeal the groups have issued a list of demands to the city that include transferring vacant property owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority, Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, and Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation to a permanent community housing trust, firing all police and city employees who do not treat unhoused people with respect, ending “homeless sweeps” and sanctioning encampments across the city.

“Maybe you don’t know them well,” Johnson said of people who are unhoused, “but you should be treating them as if they are just another person in the community and fighting fiercely at every level of government to make sure every person is housed.”

“The waiting list for public housing in big cities isn’t counted in years anymore. It’s counted in decades,” Matthew Desmond, professor of sociology at Princeton University and author of “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City,” said on a recent episode of “The Briefing,” a daily broadcast show by The Appeal. “If I applied for public housing today in our nation’s capital—I have two young kids—chances are I’d be a grandpa by the time my application came up for review.”

“Housing is something the country needs to invest in deeply because, without stable shelter, everything else falls apart,” Desmond added.