Philadelphia City Council’s Vote in Favor of Ending Cash Bail Bolsters Citywide Push

In early February, the Philadelphia City Council made history: It voted unanimously in favor of ending the use of cash bail. The resolution, passed February 1, urges the district attorney’s office and the courts “to institute internal policies that reduce reliance on cash bail” and called on the state legislature and state Supreme Court to eliminate […]

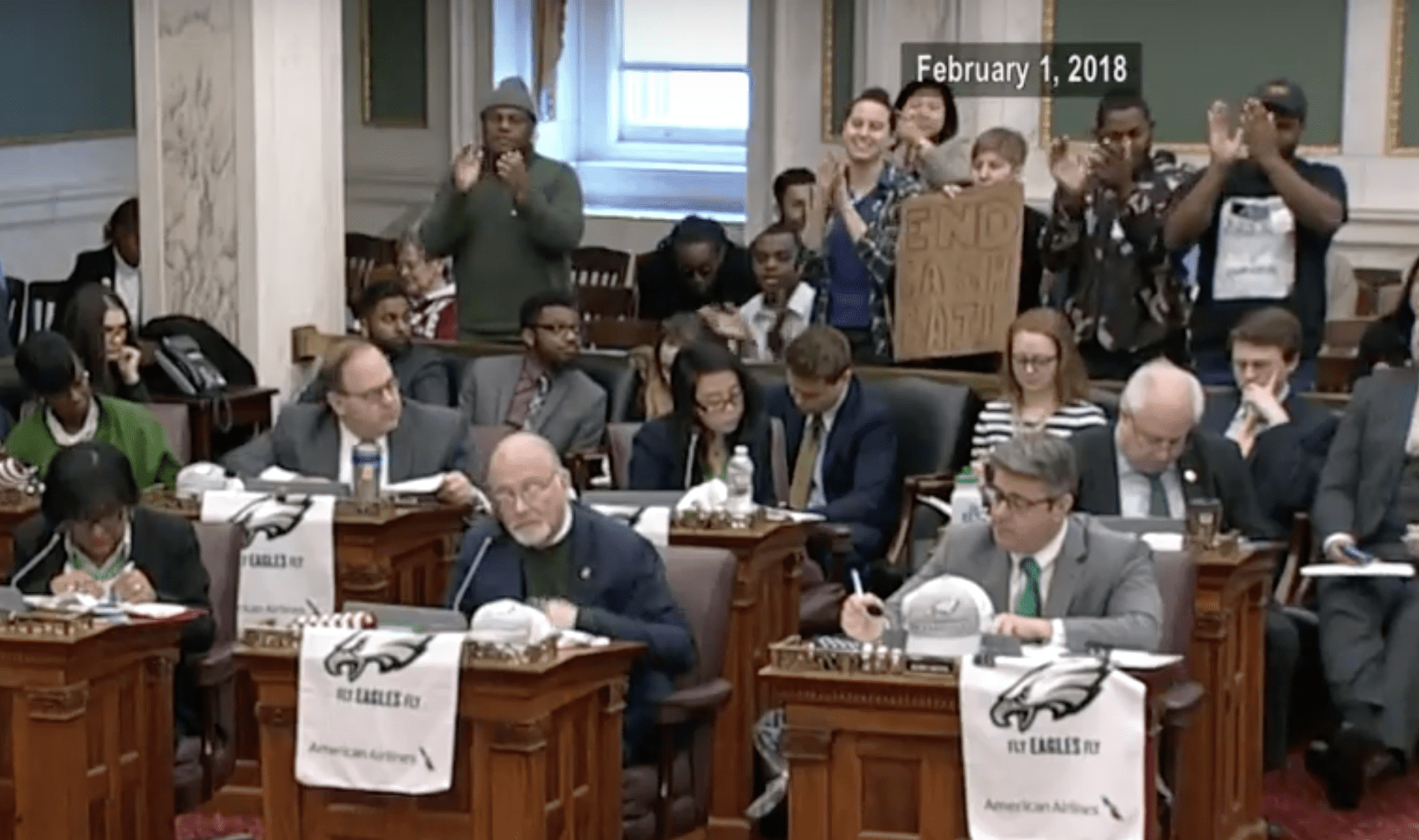

In early February, the Philadelphia City Council made history: It voted unanimously in favor of ending the use of cash bail.

The resolution, passed February 1, urges the district attorney’s office and the courts “to institute internal policies that reduce reliance on cash bail” and called on the state legislature and state Supreme Court to eliminate cash bail statewide.

The Council’s vote doesn’t have legal force; the state legislature would have to act in order to end the use of cash bail in Philadelphia or anywhere else in Pennsylvania. But advocates say it is still important — and signals that more meaningful action may be on the way.

“Even if it doesn’t have legislative heft, it’s always helpful to have such vocal support from the [city] legislature,” said Julie Wertheimer, chief of staff of the Philadelphia mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. “It just means that all three branches of government in Philadelphia are on the same page in terms of the direction we’re moving in as a city, regardless of what the state decides to do.”

Paul Heaton, academic director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at University of Pennsylvania Law School, agreed. “The City Council vote is not merely symbolic,” Heaton said in an email. “The recent vote signals some openness by the Council to consider budgetary or legislative requests from agencies that would support policies or programs that reduce cash bail, and this should encourage those interested in reform.”

Even without action from the state legislature, he said, the City Council, courts, and DA’s office can decrease the use of bail. “There is no ‘magic bullet’ solution that is going to allow the city to end cash bail,” said Heaton. “It is going to require parallel efforts across a variety of domains involving the entire criminal justice system.”

The city could provide earlier representation for detainees in the pretrial process, for instance, so attorneys could more effectively argue for release instead of bail. Judges and magistrates could use risk assessments to allow more people to be released. Perhaps most importantly, Heaton said, there should be fewer arrests in the first place, particularly for low-level offenses.

The City Council has already taken some legislative action: In 2016, it changed some low-level nuisance offenses, such as disorderly conduct or public drunkenness, into civil code violations, meaning that those who are charged are issued tickets instead of arrested. Advocates want even more offenses to be categorized as civil code violations so they result in summonses instead of arrests, effectively ending cash bail for those types of charges.

Meanwhile, municipal court has the power to formulate bail guidelines that focus on releasing people on unsecured bail — which doesn’t require arrestees to pay anything up-front to be released, only if they fail to return to court — or on non-monetary conditions, such as monitoring or drug tests. “If the president judge of the municipal court and a majority of the municipal court bench agreed on a set of guidelines making money bail an option of last resort, that could change overnight,” noted Arjun Malik, a board member of the Philadelphia Bail Fund.

“Discretion really does lie with these local actors — the courts, the district attorney’s office — to change their policies as they stand today,” added Malik.

Local actors include District Attorney Larry Krasner, who was elected in November on a pledge, among others, to end the use of cash bail. “There’s clearly vocal support from him to accelerate this work,” Wertheimer noted.

Ben Waxman, communications director for Krasner’s office, is enthusiastic about the City Council’s recent vote. “We view it very much as a positive step forward towards [the] consensus that is building around the issue,” he said. Even a few years ago, he added, bail reform wasn’t an issue that galvanized many voters; now it’s a widely discussed issue citywide.

The DA’s office plans to take action on bail reform soon, although Waxman couldn’t share specifics yet. “What we are engaged in at the moment is an internal review of current district attorney polices around how we ask for bail and for what amounts and for what types of offenses,” he said. In the next few weeks, he said, his office will have some “pretty significant announcements” coming out that will “outline a plan to move forward to turn that vision to reality.”

“Expect to see some changes,” he added.

The city’s push for bail reform got a boost in 2016, when Philadelphia was awarded a $3.5 million grant from the MacArthur Foundation to reduce the number of people held in its jails. Since then, its jail population has dropped by about 17 percent. Still, about a quarter of the people held in city jails are there because they can’t make bail. Wertheimer said it takes time to move from a grant to large-scale changes. “As you can imagine, these things, even with the funding and outside support in place, take a while to actually operationalize,” Wertheimer said.

One important change that resulted from the MacArthur grant is that if a defendant is given a bail amount of $50,000 or less for a nonviolent offense, he or she gets a review hearing five days later. According to Malik of the Philadelphia Bail Fund, about 90 percent of people who have review hearings are then released, which means they are now spending less time in jail due to an inability to afford bail. “But that’s not good enough,” he argued. “Putting them in jail for five days is incredibly destabilizing to their lives and there’s no real justification for it.”

“I don’t want to discount how much good it’s done compared to the previous status quo,” he added. “But it’s not anywhere near ending money bail. It’s not good enough.”

Ultimately, Malik hopes the City Council’s vote will help build momentum for reform. “It certainly helps put pressure on both the DA’s office and the court system, and even the state legislature, in saying, ‘Hey, Philadelphia wants to change and you need to catch up,’” he said.

Indeed, there is already pressure on the state legislature to eliminate cash bail altogether. “We’re watching to see if the state actually moves on it,” Wertheimer said. While bail reform bills have thus far been introduced but not enacted, she said, “that could change at any time.”