Pepper Spray Is Toxic, Experts Say. So Why Is It Being Used on Children?

California is one of only six states that allow staff in juvenile facilities to carry pepper spray. But LA’s coming ban is still facing pushback.

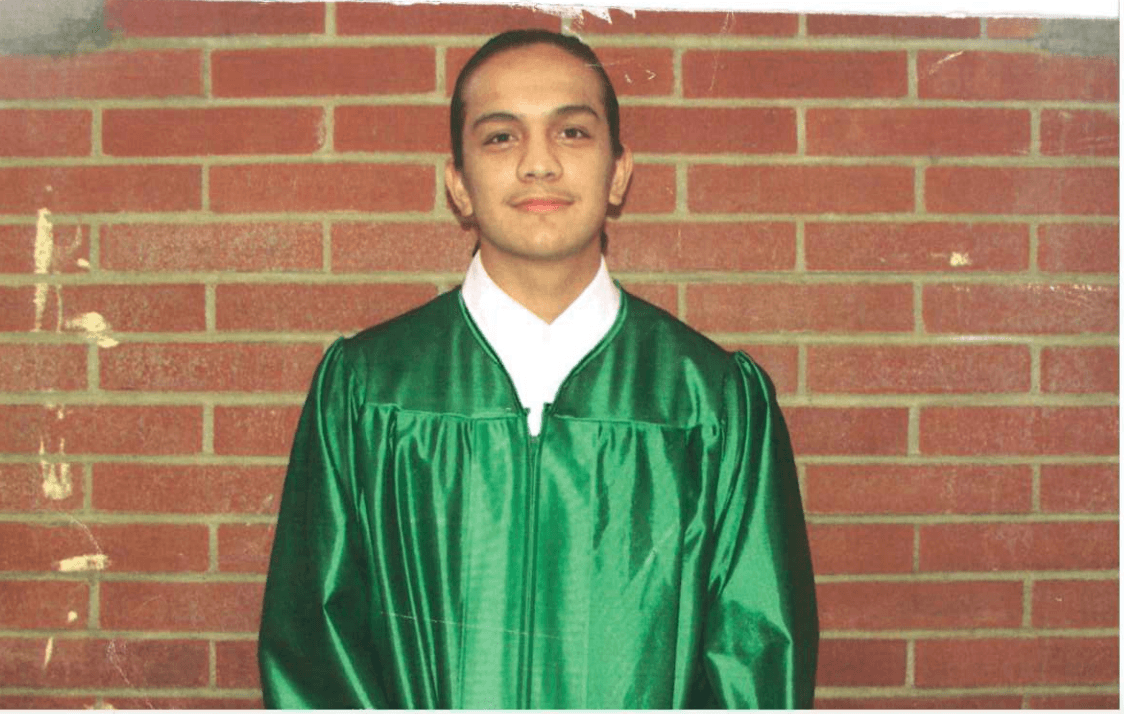

Edgar Ibarra knows more than he’d like to about the different kinds of pepper spray, also known as oleoresin capsicum or “OC spray.” That’s because he was sprayed with it several times, starting at age 15, during his time in state juvenile detention facilities in California.

There are smaller canisters known as “streamers,” and the Z-505 crowd control ones that spray a mist.

Then there are the MK9s. “It’s like this big-ass fire extinguisher type looking thing and they would just pump your room full of it until you cuffed up,” he said. “It’s kind of like a goo that gets on your skin.” It “entrenches itself in your pores,” Ibarra, now 26, told The Appeal. The goo, he said, would cause his skin to peel and blister.

“When it gets in your eyes, you’re done,” he added. “You’re not gonna see good for another two or three days.”

The Division of Juvenile Justice, which ran the facilities where Ibarra was held as a teenager, could not confirm his account as alleged, but an agency spokesperson said in an email that “the impacts and effects of the use of oleoresin capsicum are well documented.” Over the past decade, he added, the agency has worked to change how and when it is used.

But Ibarra, who works with formerly incarcerated youth as a leadership and program assistant at MILPA, a nonprofit in Salinas, California, said OC use against young people in the care of the state remains a pressing concern. A report published in May from the ACLU Foundations of California found that young people incarcerated in California’s state and county facilities were exposed to chemical agents such as pepper spray more than 5,000 times between January 2015 and March 2018. The report calls for a statewide ban on the use of pepper spray across the juvenile justice system.

The use of OC spray on young people is banned in 35 states, and seven California counties currently prohibit the use of chemical agents in their juvenile detention facilities. Proposed legislation to eliminate OC spray except as a “last resort” to “suppress a riot” in youth facilities across California failed in 2018, but in February the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to phase it out of juvenile facilities, starting this month.

Law enforcement has pushed back against the ban. The board initially asked the probation department, which supervises the county’s juvenile detention facilities, to eliminate its use of OC spray by Jan. 1, 2020, but the department asked for more time and resources to make the change.

Urgency is required here; these youth have experienced too much trauma already.

Lucy Salcido Carter Youth Law Center

Pepper spray has already been eliminated in the county’s youth camps, but the full phase-out in the remaining two juvenile halls will take until September 2020 as the department provides training for its staff on alternative methods such as de-escalation techniques and rapport building.

Lucy Salcido Carter, a policy advocate at the Youth Law Center, was disappointed by that timeline. “We recognize that staff who have been using a harmful tool need training in the use of safe tools,” she told The Appeal. “But as we know, when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. To stop using OC sprays, they must no longer be available as a tool. … Urgency is required here; these youth have experienced too much trauma already. The system should never again add to their trauma through such an unnecessary and harmful use of force.”

Los Angeles’s decision to abandon OC spray came on the heels of a report from the state’s Office of Inspector General. Use of the spray increased 338 percent in Central Juvenile Hall between 2015 and 2017, according to the report, and roughly tripled at the county’s two other halls, one of which has since been closed. In April, six LA juvenile detention officers were charged with unlawfully using pepper spray.

“Lack of adequate training, supervision, accountability systems, and policies, which may be exacerbated by an apparent lack of resources, likely contribute to out-of-policy use of and over-reliance on OC spray,” the report noted.

The inspector general found that roughly a third of staff members were responsible for the majority of OC use and, in some cases, children weren’t able to properly decontaminate themselves after being sprayed. In one instance, the report noted that young people were seen on video attempting to rinse themselves with water from the toilet after being put in a unit with a sink that did not have running water.

Though advocates pushed for immediate changes, county officials were reluctant to rush the process. In an email, Los Angeles County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl told The Appeal that the probation department needed the extra time “to ensure the safety of youth and probation staff.”

“The timetable [was] extended,” she wrote, “but we remain absolutely committed to ending the use of pepper spray in all juvenile facilities in LA County.”

Adam Wolfson, director of communications and community relations for the probation department, told The Appeal the agency is taking an incremental approach after its experience with eliminating solitary confinement for young people. “While it was certainly the right thing to do, it was done without replacing that tool with another,” Wolfson said. “What we’re trying to do is learn from that, and from best practices from around the nation, as a measured, phased approach, in conjunction with robust training.”

But Stacy Ford, the probation officers union representative in LA County, said in a phone call that he and his fellow officers have not yet received adequate training in alternatives to OC spray. They protested when the decision to phase out the spray was made in February, asking the department to reconsider and not do so without replacing it with some other tool.

Ford said he doesn’t feel safe going to work, especially without access to pepper spray. “The kids that we’re dealing with now are considered super high-risk offenders. … And not only are they violent on the streets, they’re violent in our juvenile hall,” he said, noting that attacks on staff have significantly increased in the last few years.

Because the population in LA’s youth facilities has decreased sharply over the last several years, Ford said that the young people that remain in custody are “the worst of the bunch.”

Ibarra said that type of labeling of youth dates back to the “superpredator” myth of the 1990s. Research has shown that overreliance on restraints of any kind in juvenile detention is counterproductive. “We must remember that most of the time youth who are labeled as such will take on an attitude of ‘if you wish to call me an animal, I will act like an animal,’” he said.

Carter of the Youth Law Center pointed out that other major cities have found ways to avoid OC spray. “San Francisco and Santa Clara don’t use chem spray, and they are large California urban areas with presumably the ‘problematic’ youth probation is talking about.”

Ian Kysel, author of the ACLU Foundations of California report who is now on the faculty at Cornell Law School, says that ironically, things may have gotten worse as the population in juvenile detention dwindled. “The downsizing of the Department of Juvenile Justice has meant that the vast majority of kids in California are now detained in county facilities, with very little oversight [and] almost no transparency about how young people are treated.”

This is defined by state law a tear gas weapon and should never be used against kids.

Ian Kysel author of ACLU report

According to Kysel’s report, OC spray can cause intense pain, swelling and blistering of the skin; respiratory problems; acute hypertension; eye damage; and a heightened risk of asphyxiation when used along with physical and mechanical restraint.

“The agents and officers in these detention settings have really difficult jobs,” Kysel acknowledged, “but they often talk about things like pepper spray as a tool. I mean … this is defined by state law a tear gas weapon and should never be used against kids.”

Laura Garnette, chief probation officer for Santa Clara County, which prohibits the use of OC spray on young people, said she has found the spray unnecessary because the facilities in her county are adequately staffed by employees who are properly trained. She believes that most staff are well intentioned and will gravitate toward alternative methods with proper training.

Garnette stresses that young people are not in juvenile detention to be punished. “It’s not your job to punish them, it’s your job to keep them safe,” she said of those who think they need pepper spray to do their jobs. “Pepper spray puts a barrier between you and the youth.”

Both Garnette and Carter spoke about the importance of relationships in a system that is supposed to be rehabilitative. “You can’t have a rehabilitative relationship with a young person,” Carter said, “if you’re spraying them in the face.”