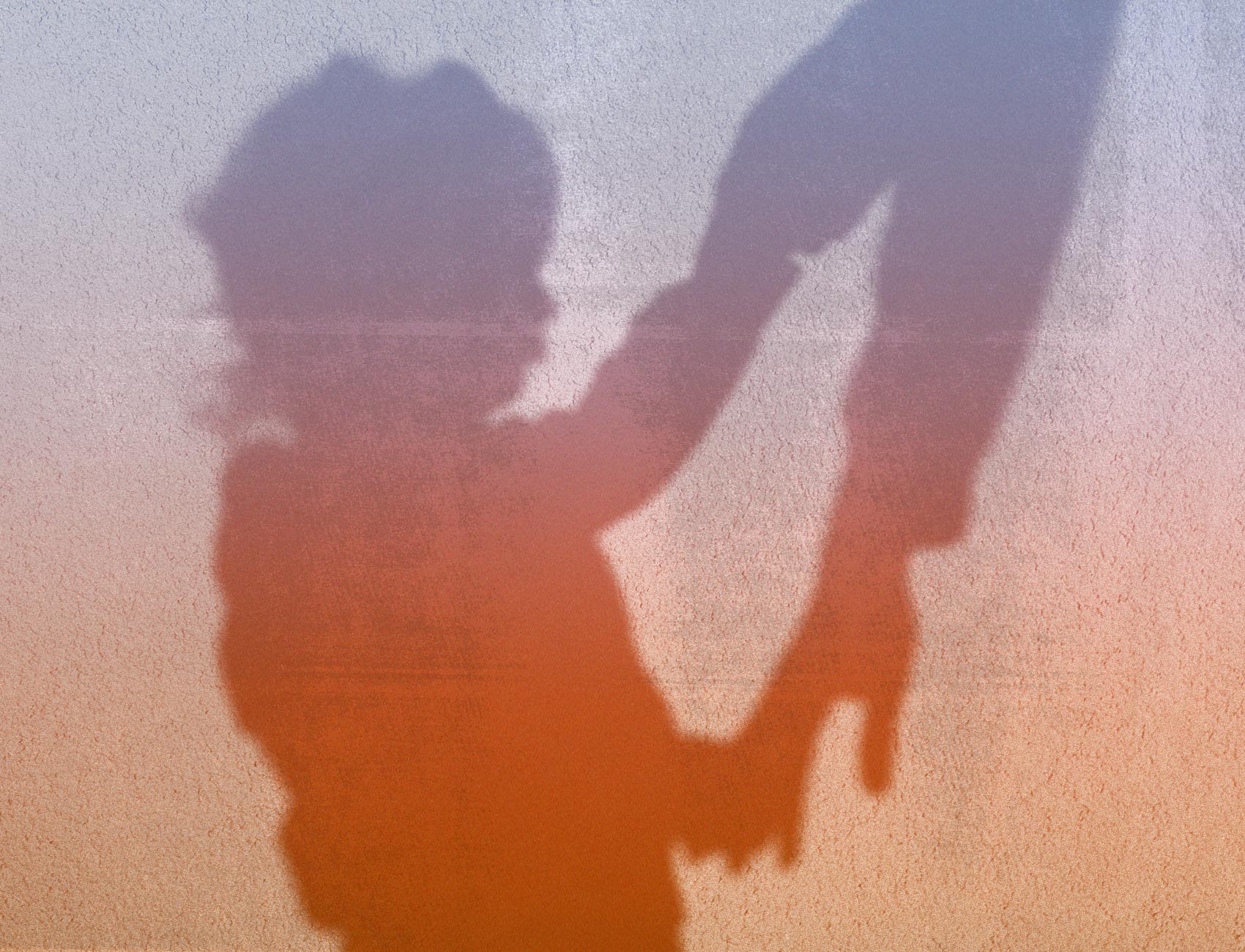

Parents Threatened With Losing Children Over Cannabis Use

Even in states where use is decriminalized, child welfare systems continue to treat it as a sign of neglectful parenting, particularly among families of color.

Ms. D, a mother of two living in the Bronx, smoked cannabis occasionally. She never smoked in front of her children, and her casual use never affected her ability to parent. So when a child protective investigator asked her if she smoked, Ms. D was forthcoming. After all, her children were healthy, happy, and well cared for, and cannabis use was decriminalized in New York and legal in many other states.

To Ms. D’s surprise, she was brought into court and charged with child neglect in part on the basis of her cannabis use. The Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) agreed that Ms. D’s children could remain in her care only if she entered into a daily drug treatment program. Even though she did not have a substance use disorder and there was no evidence whatsoever that her children were at risk in her care, Ms. D was struck with fear and couldn’t bear the thought of her children being taken from her. So she agreed. But to comply with the schedule, she was forced to give up her two part-time jobs, threatening her family’s housing stability. Meanwhile, the legal case against her for child neglect dragged on for months before ultimately being dismissed.

Unfortunately, Ms. D’s story is not unusual for Black families. Though white parents in more affluent ZIP codes also use cannabis with virtually no risk of state intervention, Black parents are subject to heightened surveillance and punishment. As public defenders representing parents in Bronx Family Court, we have seen firsthand the ways in which the state uses a parent’s cannabis use to justify intruding into the lives of low-income families of color. It is just one of the many ways in which the war on drugs reverberates today to surveil and criminalize Black and Latinx parenthood. Ms. D lost her livelihood and spent months under ACS supervision, but many parents face a much greater risk: losing the right to their children.

The harm of child welfare involvement cannot be underestimated.

Despite ample evidence that Black and Latinx people use cannabis at much the same rates as white people, parents of color are much more likely to be targeted, surveilled, and policed for cannabis than their white counterparts. Such bias causes disparities throughout the child welfare system. One study found that Black children are 6.2 times more likely to be involved in a report of abuse or neglect than white children, 7.8 times more likely to be involved a report found to be credible by the child welfare agency, and 12.8 times more likely to be placed in foster care. Moreover, in New York, Black children remain in foster care longer, on average, than white children.

The harm of child welfare involvement cannot be underestimated. It separates Black and Latinx families, destabilizing precious bonds between parents and children. Research has shown that initial child protective involvement can derail parents’ efforts to secure permanent housing, and can cause them to lose employment and public benefits when their children are removed. Further, the trauma suffered by children who are removed from their parents makes it more likely that those very children, down the line, will become involved in the child welfare system themselves. The result of these insidious disruptions, in turn, undermines the ability of marginalized communities to build power and resist structurally unjust systems.

The growing national movement toward cannabis legalization has been successful thus far in 11 states, with many more states poised to legalize or substantially decriminalize it. Often missing, however, from this movement has been an effort to ensure that a parent’s use of cannabis is not used unnecessarily to separate children from their parents in child welfare prosecutions.

At the demand of advocates, New York City has taken some initial steps to ensure that parents are not prosecuted in the child protective system because of cannabis use. This year, the City Council held a hearing to assess and address the impact of cannabis policies on child welfare. At the hearing, ACS Commissioner David Hansell testified that the agency uses neither a parent’s cannabis use nor a positive toxicology alone as a basis for child protective determinations. But this testimony ran contrary to what advocates, including The Bronx Defenders, still saw every day on the ground. The testimony of parents affected by the child welfare system and family defense attorneys revealed the ways in which ACS continued to use a parent’s cannabis use as a reason to bring families to court, separate families, and delay reunification.

Seeming surprised to learn that its daily practice was in discord with stated policy, ACS issued an all-staff bulletin shortly thereafter, clarifying the cannabis policy. Specifically, the bulletin stated that cannabis use, without an articulable connection to the child’s physical, mental, or emotional condition, cannot be a basis for indicating reports or filing neglect cases, without further inquiry into the impact of such use on children’s safety. More recently, the City Council has called on ACS to implement even stronger policies de-linking cannabis use from child welfare prosecutions. Though good news for New York City parents, these steps only stretch so far as the city’s five boroughs, and are insufficient to address child welfare actions statewide.

Indeed, child welfare prosecution of cannabis use varies depending on where a parent lives in New York State. Kate Woods, a family defense attorney and deputy director of Legal Assistance of Western New York, acknowledges that the opioid crisis has, in many ways, eclipsed cannabis use cases. Nevertheless, the local child welfare agency and judges alike often treat cannabis use as a proxy for poor parenting, as Ms. D’s experience shows.

Recognizing the limits of a patchwork approach, the drafters of this year’s proposed cannabis legalization bill in New York addressed how cannabis use should be used in child protective proceedings. Their proposed language made clear that a parent’s cannabis use alone could not be the sole basis for child welfare proceedings, and codified existing state law mandating that a positive toxicology for cannabis or any other substance alone is insufficient for a finding of neglect. Though the legislation did not pass in this year’s session, these protections must be preserved in future legalization efforts.

We’ve already seen what happens when those safeguards aren’t in place. Even in states where cannabis has been decriminalized or legalized, some child welfare agencies still cite cannabis use as grounds to separate families, delay reunification, and foreclose vast swaths of employment opportunities for poor people of color.

Colorado’s legalization process serves as one such cautionary example. After the state voted to legalize cannabis use, its 2014 legalization laws did not address the ways in which cannabis use might continue to be cited as a basis for child welfare involvement. Indra Lusero, staff attorney at National Advocates for Pregnant Women and director of the Colorado-based birth justice organization Elephant Circle, explains that Colorado’s myopic focus on decriminalization preserved “a whole arm of the law that would continue to seriously negatively impact people’s lives.”

We’ve already seen what happens when those safeguards aren’t in place.

In fact, after legalization, advocates began to see an uptick in child welfare cases involving allegations of parental drug use. Though it’s hard to document a direct link to legalization, a 2016 Denver Post article found that the proportion of child welfare cases involving parental and or caretaker drug use increased by two full percentage points between 2013 and 2015.

Lusero notes that after legalization, they saw cannabis treated more harshly than it had been by child welfare workers. Lusero postulates that perhaps because of legalization, child welfare workers felt that they needed to guard more vociferously against “untrustworthy,” “irresponsible” parents with easier access to cannabis—especially pregnant people.

Despite losing the legislative battle, Colorado advocacy groups like the Coalition to Protect Children and Family Rights have worked to address these unforeseen harmful outcomes by demanding data-tracking mechanisms within the child welfare system. Additionally, in order to provide parents with high-quality legal representation in child protection proceedings, Colorado created an institutional provider that specifically represents parents.

By contrast, Massachusetts is an example of a state where the law explicitly addressed parental cannabis use in child welfare proceedings. When Massachusetts legalized cannabis via ballot initiative in 2016, the legalization statute included provisions that limited the ways in which child protective agencies could use cannabis to intrude in families’ lives. The statute clarified that states cannot use cannabis use as a “primary or sole” basis for family separation, denial of visitation, substantiation of a neglect claim, or imposition of a service plan.

Scott Chapman, an attorney at the Committee for Public Counsel Services in Northampton, Massachusetts, which represents parents and children in child protection proceedings, said that although judges may discuss a parent’s cannabis use, they do not make major decisions based on that alone. In Chapman’s experience, “cannabis use seems to be an issue that the court evaluates in the same category as alcohol use.” Chapman notes, however, that despite these protections, prosecutors and judges in other, less progressive counties throughout Massachusetts continue to separate families and find parents guilty of child neglect based, at least in part, on their use of cannabis.

Even as some judges and child protective agencies are moving toward framing cannabis use as akin to alcohol use, Lisa Sangoi, co-founder and co-director of Movement for Power, warns that certain factors differentiate cannabis from alcohol, especially in the state’s ability to surveil it. Many newborns and parents are drug tested in hospital settings, and cannabis metabolites remain detectable for up to one month. After speaking with caseworkers and family court judges across the country for a report to be published by NYU Law Family Defense Clinic and Movement for Family Power, Sangoi concluded that even in states that have legalized cannabis use, “you’d be hard-pressed to say there has been a significant decrease in the policing of cannabis use while pregnant.”

Legalizing cannabis is a necessary step away from war on drugs-era policies that have caused so much harm to low-income communities of color. But legalization alone will not stop the child welfare system from using marijuana as a proxy for poor parenting, and thus, a basis for family monitoring, disruption, and separation. States must enact comprehensive change across non-criminal prosecutorial platforms to help the communities most often targeted by drug prohibition move past its devastating collateral consequences.

Miriam Mack and Elizabeth Tuttle Newman are staff attorneys at The Bronx Defenders’ Family Defense Practice.