Oklahoma Governor Releases 21 Prisoners Shut Out Of Drug Sentencing Reform

But more than 1,100 others are still serving sentences that voters decided were too harsh.

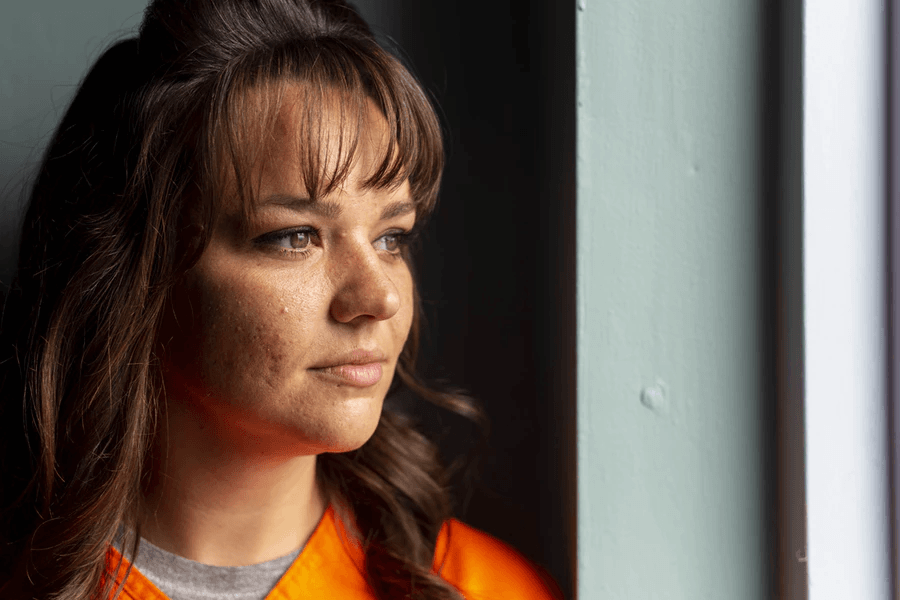

On Dec. 5, 26-year-old Kayla Jo Jeffries walked out of Oklahoma’s Kate Barnard Correctional Center after three years of incarceration. She returned home and reunited with her two daughters, the younger of whom had been born while she was incarcerated. She almost immediately began a hairdressing job.

Jeffries had been prepared to remain in prison until her daughters were much older. She was serving a 20-year sentence for three drug-related felonies she committed when she was 18. She had worked hard from inside prison to get clean and to earn a GED and a cosmetology license. The Pardon and Parole Board recognized her accomplishments and sent her home in time to spend the holidays with her family.

“God’s good and I believe he’s going to see us through,” Jeffries told The Appeal, explaining how life on the outside is “overwhelming,” but exciting nonetheless.

Jeffries was one of 21 people, mostly women convicted of drug possession, whose sentences were commuted Dec. 5 by Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, a Republican. Each of the 21 individuals were serving a sentence of more than 10 years—together, more than 340 years—for crimes that are now punishable by a no more than a year in prison and a $1,000 fine.

Two years ago, nearly 60 percent of Oklahoma voters approved State Question 780, a sentencing reform measure that went into effect in July 2017 and reclassified drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor.

When Jeffries, then more than a year into her sentence, found out that the sentencing reform had been approved, she said she was “hopeful.” She felt good knowing the measure would affect men and women like her in the future. But because the law was not retroactive, she and hundreds of others would remain in prison on their original sentences, barring a reprieve from the governor.

Although Fallin’s 21 commutations recognized the new reform, many more people remain in prison on sentences voters decided were disproportionately harsh. More than 1,100 people are still serving felony sentences for drug possession, according to Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, a nonprofit organization that pushed for the law change and the recent commutations.

I need help. I am ready for recovery.

Chad Mullen an Oklahoman sentenced to ten years for drug possession

Oklahoma is now the most incarcerated state in the nation after Louisiana enacted reforms to reduce its prison population. An unusually high share of prisoners are serving time for drug possession in Oklahoma.

The state’s prison population has continued to grow and the Department of Corrections asked for a $1.57 billion budget for the coming fiscal year, which it would use to add 5,000 beds to its facilities. Before 2017, Oklahoma’s prison population had grown by almost 10 percent in five years at a time when other states have cut down on incarceration and reduced crime.

Chad Mullen, a 26-year-old who was sentenced before the passage of State Question 780, wrote to The Oklahoman from prison to explain how he feels serving a 10-year sentence for felony drug possession after the law changed.

“Here I am, Chad Mullen with 2,600 days left on a 10-year sentence for an addiction,” he wrote. “I need help. I am ready for recovery. Actually past due.”

To help people like Mullen, advocates are pushing for the law to apply retroactively. Kris Steele, former Republican speaker of the state House and now the executive director of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, told The Appeal that such a change has broad support among lawmakers.

“It looks very promising,” he said. “There’s a lot of interest. We have both Republican and Democrat elected officials who are stepping up and leading the charge to accomplish the goal of retroactivity.”

Yet an effort to apply the change retroactively failed this year. The Republican chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who has since left office, refused to hear the bill largely because of pressure from district attorneys.

“The biggest barrier to reform to Oklahoma has historically been prosecutors,” Steele said.

Most district attorneys in the state criticized State Question 780 before and after its passage. They spread false narratives about the measure, saying it would make Oklahoma “more liberal than California and Washington state” when it comes to drug possession. After it was approved by voters in 2016, the Oklahoma District Attorneys Council pressured the legislature to water it down by passing legislation giving prosecutors the power to prosecute people for felony drug possession within 1,000 feet of a school. The legislation failed, and sentencing reform opponents were unable to reverse the ballot initiative. But many remain opposed to reform and say they will do what they can to hold on to strict sentencing guidelines.

The biggest barrier to reform to Oklahoma has historically been prosecutors.

Kris Steele executive director of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform

“They are resistant to change because of fear of losing power or control,” Steele said. “Maybe it’s financial reasons because so much of their budgets are also funded through fees and fines and payments on the backs of people who commit crimes.”

Trent Baggett, executive coordinator of the Oklahoma District Attorneys Council, said in a phone interview that his organization will continue to study whether State Question 780 should apply retroactively.

“I don’t want to say, knee jerk, that we would support [retroactivity],” he said. “I think the individual cases should be reviewed. That would be like saying, ‘just open the doors and let them all out.’ That’s not a fair thing either. Those individuals need to have their cases looked at and their experiences in prison considered.”

The Parole and Pardon Board sent another group of nine people—a majority women convicted of felony drug offenses—to Fallin’s desk last week with favorable recommendations. She is expected to consider them in the coming weeks and issue their commutations in what could be another emotional ceremony.

Still, the commutations are a small step for Oklahoma. In a blog post in April, Ryan Kiesel, the executive director of the ACLU of Oklahoma, compared the state’s incarceration problem to a tumor. By approving of incremental reforms, like individual commutations, Fallin is telling the state that the tumor is no longer growing. What she can’t say, Kiesel noted, is that the tumor is shrinking.

“[We] should be asking the question why, in this moment when lawmakers at both ends of the political spectrum are signaling their willingness to tackle this crisis, when polls show voters support bold reforms, that this is all we get,” he wrote. A recent poll released by lobbying group FWD.us found that four out of five registered voters in the state believe it’s important to reduce the number of people incarcerated, and 76 percent support making State Question 780 retroactive.

Not only does Oklahoma’s prison population lead the nation but the state also incarcerates women and African Americans at a higher rate than any other. And as of late 2017, drug possession was still the top crime for prison admissions in Oklahoma, as prosecutors charge individuals using the sentencing laws at the time of their crime and not at the time of their sentencing.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Jeffries said of the people still serving the outdated sentences. “There’s definitely a need in Oklahoma, but I believe we’re starting to see the beginning of those changes coming to pass right now.”

Steele said that making State Question 780 retroactive is part of a larger plan to help Oklahoma join the dozens of states that are successfully reducing their prison populations.

“We realize that we have a severe problem with mass incarceration,” he said. “We also realize that we didn’t get to these outcomes overnight and we’re not going to undo them overnight. But we have a logical, methodical plan in place to systematically reduce the number of people incarcerated in Oklahoma and retroactivity is just a piece of that puzzle.”