NYC Prosecutors Are Stoking Fear About the Mass Bailout, But Their Arguments Don’t Add Up

District attorneys’ comments belie the true purpose of bail in New York and ignore the safety risks of jail itself.

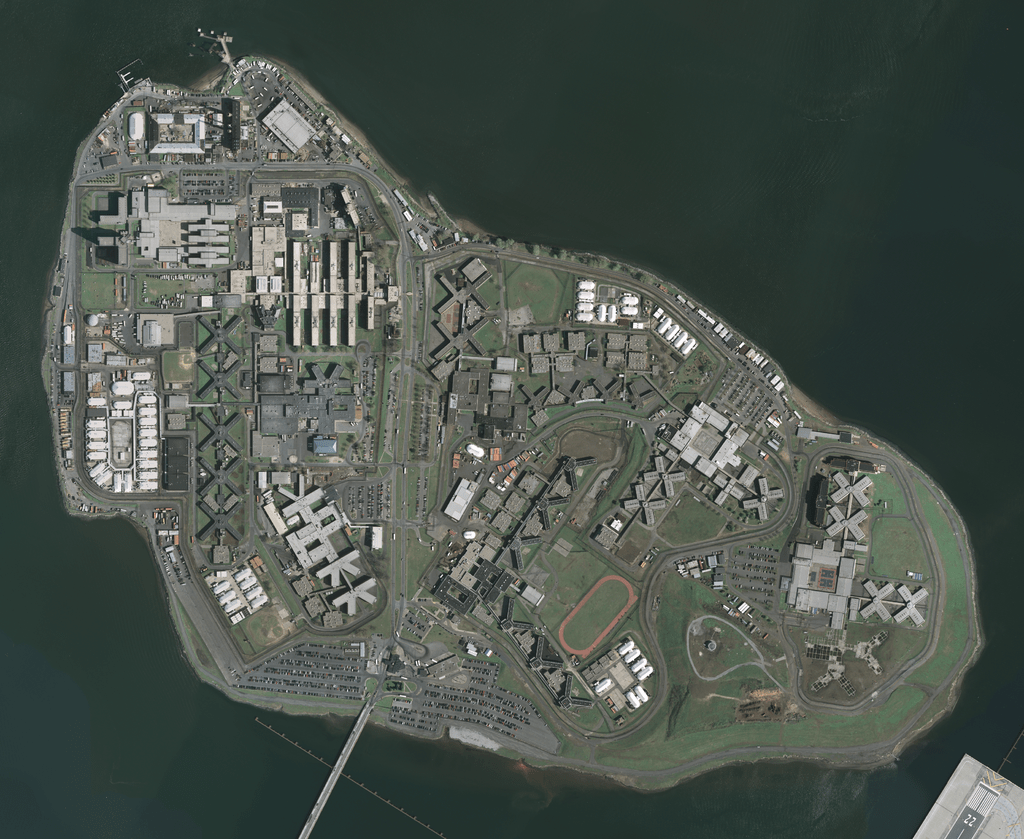

Throughout October, the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights foundation will be working to bail out hundreds of people from New York City’s jails. The organization originally planned to target two facilities in the city’s sprawling Rikers Island jail complex: “Rosie’s,” or the Rose M. Singer Center, which detains women, and the troubled Robert N. Davoren Complex, which had held boys ages 16-17. As of Monday, the city had moved the teens to a juvenile facility to comply with the state’s “Raise the Age” law, although they appear to remain as eligible for bail as before. That leaves roughly 250 women who are eligible for bail in Rosie’s, and fewer than 100 teenagers who are eligible in the new location.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, law enforcement officials quickly assailed the proposal. The president of the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, Elias Husamudeen, immediately raised the specter of those released committing crimes while on bail, as did four of the five elected district attorneys in New York City (Michael McMahon of Staten Island weighed in later). The prosecutors all suggested that the bailout was jeopardizing witnesses and victims, with Queens DA Richard Brown simply saying, “It is clearly a threat to public safety.”

Such an aggressive response by law enforcement to what is ultimately a small-scale proposal is completely predictable. Their arguments, however, are deeply problematic.

Let’s just start with the fact that New York is one of four states in the country where prosecutors and judges cannot take a defendant’s likelihood of committing another crime into account when setting bail, which is intended solely to ensure appearance at trial. So when Mayor Bill de Blasio’s spokesperson says the mayor supports bailing out those who “don’t pose a public safety risk,” she is essentially admitting that the mayor’s office is okay with using a defendant’s poverty to circumvent the state’s bail law.

Now, to be clear, Bronx DA Darcel Clark is correct when she says that there could be some public safety risk from releasing someone from Rikers without any sort of re-entry plan. But the solution is not to capitalize on defendants’ poverty and use bail to (illegally) lock them up—not only because doing so violates New York’s bail statute, but because Rikers is itself a dangerous and violent place.

At the same time, it is important that any solution not be counterproductive. Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez, for example, is encouraging witnesses and victims to get orders of protection against those being bailed out. But as public defenders are quick to explain, such orders often fail to reflect the messy, intertwined nature of violence in the city, and they can push defendants into homelessness and unemployment, which might actually make things riskier.

There are two other conceptual problems with the prosecutors’ decision to stoke people’s fears of more offending. To start, all the people who the foundation will bail out were eligible for bail in the first place. Had each of them made bail at their arraignment and left the courtroom, one by one, over the course of weeks or months, no one would have said anything. It would have been the system working as it is designed to. So why is the release of a small number of them in a short window of time suddenly a cause for alarm? The most plausible explanation seems to be that each defendant making bail at arraignment was not actually the goal, that the purpose was to use unaffordable bail to ensure systematic confinement—even though New York State law requires judges to consider a defendant’s ability to pay bail and provides up to nine ways judges can release defendants to ensure poverty alone doesn’t trap them in Rikers.

And let’s be clear: The action taken by the foundation, while laudable, is relatively minor in total scope. Rikers currently releases approximately 50,000 people every year, so the few hundred that the foundation will help leave jail constitute less than 1 percent of the total number flowing out of Rikers every year. It seems unlikely that a 1 percent increase will lead to any noticeable increase in crime. (And contrary to what some law enforcement types have said, evidence indicates that people bailed out via bail funds are just as likely to show up as those bailed out by family or friends.)

Finally, any risk to victims or witnesses has to be balanced against the risks to those detained in Rosie’s and at the Horizon Juvenile Center, where the teens formerly incarcerated in Davoren are now housed. Rikers Island is a violent, dysfunctional place. The city’s own independent commission that looked into conditions on Rikers quoted family members of detainees calling the place “Torture Island.” Rikers operated under a “code of violence,” the commission reported, and life there was defined by “brutal treatment” and “inhumane conditions.” In fact, the commission noted that those conditions were particularly dangerous and antithetical to re-entry for women and juveniles—the very populations the bailout targets. And Horizon is currently facing a federal investigation into the claim that the children detained there were sexually abused by staff for years.

By talking about the harms to victims and witnesses but ignoring those faced by the people on Rikers and at Horizon—people who retain the presumption of innocence, though that should hardly matter when talking about treating people with basic human decency—the prosecutors are reinforcing the dangerous politics of punishment. Criminal justice decisions often operate under fear of the “Willie Horton Effect,” which means that any act of leniency is politically risky, since the person out on bail could commit a crime that gets sensationalized attention. Needlessly keeping someone locked up, meanwhile, remains relatively riskless for politicians, since the costs are borne by a population mostly out of sight and whose harms aren’t considered relevant in the first place.

Even if New York’s prosecutors ultimately do not impede the foundation’s efforts, their rhetoric is disappointing. Much of criminal justice reform is about making the general public think more carefully about the needless, preventable, and often counterproductive harms that the system creates, and the prosecutors’ reactive “what about public safety?!” proclamations directly undermine such efforts, and only serve to strengthen the public’s willingness to continue to cage women and teens.