Not A Cardboard Cutout: Cyntoia Brown and the Framing of a Victim

The evening of August 6th, 2004, 16-year old Cyntoia Brown shot and killed Johnny Allen, a 43-year-old Nashville resident who picked her up for sex. It was an act of self defense, she explained to police later; after Allen took her to his house, he showed Cyntoia multiple guns, including shotguns and rifles. Later in bed, as she described in court, he grabbed her violently by the genitals, his demeanor became threatening and, fearing for her life, she took a gun out of her purse and shot him.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

The evening of August 6th, 2004, 16-year old Cyntoia Brown shot and killed Johnny Allen, a 43-year-old Nashville resident who picked her up for sex. It was an act of self defense, she explained to police later; after Allen took her to his house, he showed Cyntoia multiple guns, including shotguns and rifles. Later in bed, as she described in court, he grabbed her violently by the genitals, his demeanor became threatening and, fearing for her life, she took a gun out of her purse and shot him.

Though Cyntoia acted to protect herself from the violence of an adult client, Nashville prosecutors argued that she shot Allen as part of a robbery. Cyntoia was tried as an adult and was convicted of first degree premeditated murder, first degree felony murder and “especially aggravated robbery” two years after her initial arrest on August 25th, 2006. She is currently serving concurrent life sentences in Tennessee and will only be eligible for parole after serving 51 years in prison.

In late November, Cyntoia’s case roared into the headlines again when celebrities like Rihanna, Kim Kardashian, and Lebron James shared details of her conviction on social media. Rihanna posted on Instagram: “Did we somehow change the definition of #JUSTICE along the way?? Something is horribly wrong when the system enables these rapists and the victim is thrown away for life! To each of you responsible for this child’s sentence I hope to God you don’t have children, because this could be your daughter being punished for punishing already!” Kim Kardashian shared on Twitter that she had reached out to her personal attorneys to ask about how to #FreeCyntoiaBrown.

It’s unclear why Cyntoia’s case has re-emerged to capture the public’s imagination 13 years after her arrest. Charles Bone, one of Cyntoia’s lawyers, told Buzzfeed that he didn’t know why celebrities were now discovering Cyntoia’s case, but that he welcomed the attention. “This issue, in general, is worthy of a lot of publicity,” Bone said, “especially in the culture in which we live today.”

As petitions calling for Cyntoia’s release and letters demanding clemency circulate online, it’s worth considering the issues raised by Cyntoia’s conviction and the renewed push to free her from prison.

Here’s what has been established about her case in the court record: Cyntoia, who at the time of the incident was living in a room at a Nashville InTown Suites, said she went home with Allen because her pimp and boyfriend Garion McGlothen, nick-named “Kut Throat,” insisted that she needed to earn money. Kut Throat abused her physically and sexually throughout the approximately three week period in which she lived with him.

Cyntoia herself was able to talk about the night of her attack, and Allen’s death in the 2011 PBS documentary, “Me Facing Life: Cyntoia’s Story.” Cyntoia explained that she was looking to get a ride to East Nashville to engage in street-based sex work when she met Allen, who was scouring a Sonic Drive-In parking lot for sex workers. Allen propositioned her and attempted to haggle her down from $200, to $100; they finally agreed upon $150.

Cyntoia characterized her survival strategies as survival sex work or teenage prostitution for an adult pimp. While she says that she was coerced into sex work by Kut Throat, Cyntoia never described herself as a child sex slave, a term that is now being used to characterize her experience by some advocates on social media. Such sensationalist language is reductionist and obscures the complexities inherent in the experiences of young people in the sex trade and street economies. It is more helpful to turn to young women in the sex trade themselves for a better understanding of the terms they use to describe their own experiences.

Shira Hassan has worked with girls involved in the sex trade and street economies as the former co-director of the now defunct Chicago-based Young Women’s Empowerment Project. She defines the sex trade as “any way that girls are trading sex or sexuality, or forced to trade sex or sexuality, for anything like money, gifts, survival needs, documentation, places to stay, drugs.”

Survival sex and involvement in the sex trade are often the only means for young people to provide for themselves when they leave home. This is especially true for youth of color, queer and trans youth, who have less access to resources and opportunities. The realities faced by most teenagers engaged in survival sex are shaped by unsafe homes and housing, lack of access to employment, affordable housing, health care, including gender affirming health care, mental health resources, poverty, racism, queerphobia and misogyny.

The street economy, Hassan explained, encompasses “anything that you do for cash that’s not taxed. Whether that’s hair braiding, whether that’s selling CD’s on the corner, something that you’re gonna do that’s gonna get you money that isn’t reportable. Both of these methods are ways that girls have found to survive when they’re street-based.”

Trafficking, on the other hand, refers to any form of labor — including, but not limited to, sexual labor — by force, fraud or coercion. It’s true that there are young people who are trafficked and who experience extraordinary violence in the sex trade. But it is important not to assume that every young person who trades sex for money is trafficked, even if the law defines everyone under the age of 18 who trades sex as trafficked, regardless of their actual experience. Doing so ignores the complexity of their experiences — and does a disservice to them by denying them any agency or self-determination, including to define their own experiences and demand their own solutions. Their lives should not be flattened in the service of “perfect victim” narratives.

Cyntoia is not a cardboard cutout upon whom other adults can project their narratives of youth involvement in the sex trades. She is a young woman who has experienced horrible violence, but that is not all she is. She has her own story to tell, but by portraying her as a victim without agency, some of Cyntoia’s advocates make it more difficult for her story of self-defense, her fight to survive, and her resistance to violence to be respected. We need to find a way to describe all of her realities — both as a survivor of violence with the right to defend herself, and as a young woman who was doing her best to survive.

Will this renewed focus on Cyntoia serve to improve the lives of all young people in the sex trade and street economies? Or will the current attention and the framing of her as a victim of sex “slavery” or trafficking serve to further marginalize them by silencing their voices and complexities in service of pursuing a “perfect victim” narrative, one that Black women are routinely excluded from?

The consequences for young women who don’t fit the “perfect victim” narrative are significant — both in terms of being harshly punished for self-defense, or being framed as “traffickers” themselves and then threatened with long sentences under new laws ostensibly passed for their own protection. Even if not subjected to punishment by what we call “the criminal legal system” — because we believe there is no justice in this system — many of the new “trafficking” laws passed at the state level over the past decade may force them back into foster care and other systems that they have fled because of the harm they experienced. Or, coerce them into “treatment” that does nothing to address the conditions under which they entered the sex trade in the first place. If they don’t “comply” with what is expected of them as “perfect victims,” then they, like many other survivors of violence, find themselves caged in a cell instead of receiving the support they need and deserve.Prosecuting and incarcerating survivors of violence puts courts and prisons in the same punitive role as their abusers, which compounds and prolongs victims’ experience of ongoing trauma and abuse.

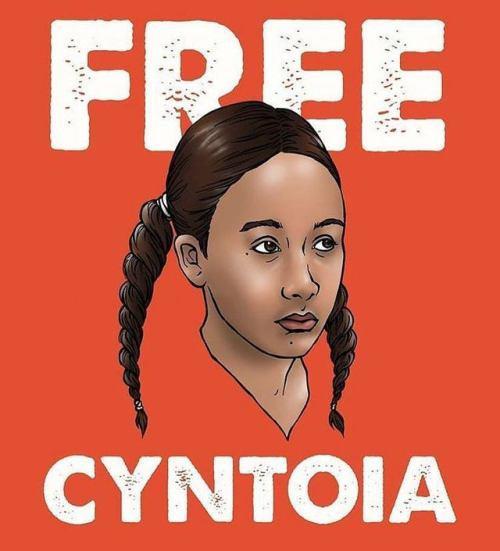

The push to keep Cyntoia a child is also troubling. Since the recent surge of interest in her case, graphic artists have created an image of Brown with the pigtails she donned during her trial, when she was 16, accompanied by the text, “Free Cyntoia.” Another image of her at a similar age has been appropriated into a meme, juxtaposed with the rapist Brock Turner’s mugshot, using her incorrect age, and unconfirmed case circumstances. Other memes have claimed a “paedophile sex trafficking ring” was responsible for the violence visited upon Cyntoia. Why are these images and memes being circulated? Is an adult, 29-year-old Black woman an unsympathetic victim? If so, why? Acknowledging trauma and resilience are often ignored in favor of the driving desire by the media and public to support only a perfect victim. Perfect victims are submissive, not aggressive; they don’t have histories of drug use or prior contact with the criminal legal system; and they are “innocent” and respectable.

The reality, however, is there are no perfect victims. Twenty-nine-year-old Cyntoia deserves to be free from prison and absolved of this “crime,” no less than 16 year-young Cyntoia should have been.

Cyntoia’s story, while tragic and unfair, is not exceptional. As we were writing this piece, Alisha Walker, another criminalized survivor, called us from Decatur Correctional Center, an Illinois prison where she has been incarcerated since March of this year (and, unless she is freed, will have to spend another 10 years). “She’s an amazing woman, so brave,” Alisha said of Cyntoia’s case. “Shit, she was 16? No one should be punished for enduring harm themselves. That girl was just doing what she had to do.”

Alisha Walker was just 19 years old when, in 2014, she was forced to defend herself and a friend from a violent client who demanded that they have unprotected sex with him and threatened them with rape and a knife. Alisha, like Cyntoia before her and so many before them, fought back. Her act of self-defense was met with the violence of a racist court system that branded her a manipulative criminal mastermind. Alisha and Cyntoia were both young Black women whose bodies were inscribed with inherent criminality and were, to some degree, presumed guilty until proven innocent. But the judicial system as currently constituted would and could not have allowed them to be seen as innocent. Instead, Cyntoia and Alisha’s radical acts of self-love and preservation were criminalized by those with authority; each had the carceral weight of racism and whorephobia stacked against them.

Courts historically mete out punishment disproportionate to the acts of self-defense by black women, femmes, and trans people. This criminalization of self-defense pre-date Cyntoia; we see this in the cases of survivors Lena Baker, Dessie Woods, and Rosa Lee Ingram for example. It has continued long after Cyntoia’s sentencing thirteen years ago. We see this same disproportionate punishment in the more recent cases of GiGi Thomas, CeCe McDonald, and Ky Peterson. And these are just the names and stories that we know; there are many others that never grab headlines or inspire social media or grassroots defense campaigns.

Let’s #FreeCyntoiaBrown — not only from the cage she has unjustly been held in for the past 13 years for fighting for her life, but also from narratives that take away her agency and police and control what it means to be a survivor of violence. And let’s do the same for all young people in the sex trade, and all survivors of violence. In the words of the Young Women’s Empowerment Project, “Social justice for girls and young women in the sex trade means having the power to make all of the decisions about our own bodies and lives without policing, punishment, or violence…We are not the problem — we are the solution.”

Mariame Kaba is an organizer, educator & curator who founded & directs Project NIA and is a co-founder of Survived & Punished among other projects and organizations. Brit Schulte is a community organizer, member of the Justice for Alisha Walker defense campaign, and underemployed art historian currently based in Brooklyn.