New York Protests Could Finally Push Through Increased Police Transparency

Lawmakers are targeting a statute that has been used as a cudgel to bat away almost any inquiries into police misconduct.

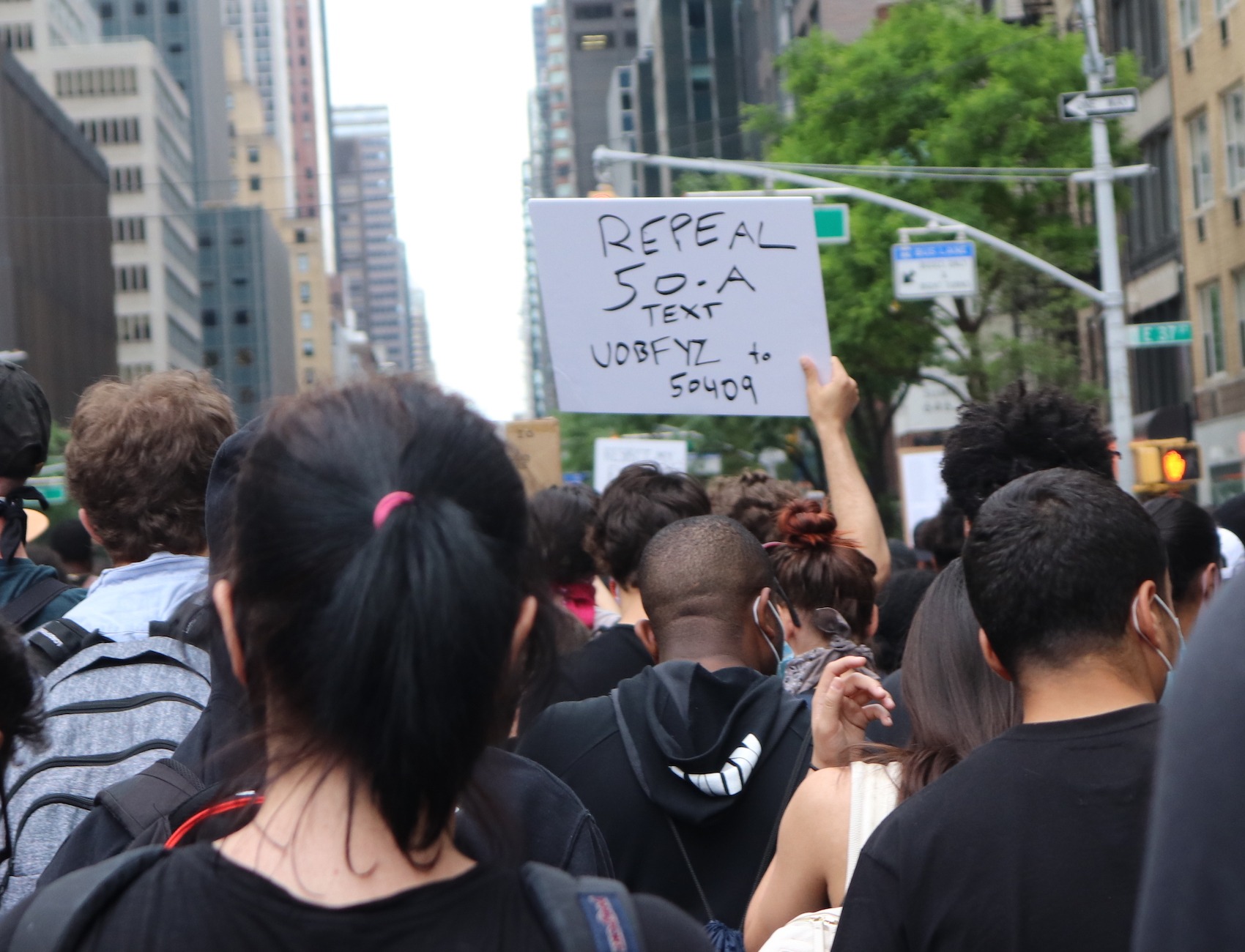

Protesters taking to the streets across the country since George Floyd’s death have one common demand: end police violence. Some are calling for transformational changes to reach that goal—shrinking police budgets, or abolishing the police altogether. In the short-term, meanwhile, the protests are giving local advocates a chance to go after policing policy they’ve long seen as unjust.

A prime example is in New York, where police disciplinary records are currently shrouded in secrecy. Section 50-a of the state’s civil rights law keeps confidential any personnel records that are used to evaluate a police officer’s, firefighter’s, or corrections officer’s performance, unless that officer or a court order permits their release. The law was enacted in 1976, purportedly as a way to ensure civil servants’ privacy, as well as to protect testifying cops from overzealous cross-examination by defense attorneys. But the law has become a cudgel to bat away almost any inquiries into police misconduct, especially in recent years.

In its current interpretation, 50-a is widely considered to be one of the nation’s most restrictive state laws for police transparency and accountability. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, who has been in office since 2014 and oversees the largest and one of the most militarized police departments in the country, has espoused a strict interpretation of 50-a. His administration has argued that it forbids police departments from releasing officers’ disciplinary records, even with personal information removed. In 2017, a state appellate court agreed, striking down legal organizations’ requests for such records in two separate cases, and in 2018, the state’s highest court upheld that interpretation, setting in stone the restrictive reading of the law.

In one of the 2017 rulings, the court mentioned that, if advocates wanted to improve police accountability, “the remedy … must come not from this court, but from the legislature.” But at the time, the state senate was controlled by Republicans, who wanted nothing to do with police reform. The first opportunity to reform the law came in January 2019, when Democrats—including a slew of progressives in favor of dramatic police reform—took over both chambers of the state legislature. Lawmakers introduced bills to reform or outright repeal 50-a throughout 2019, and the legislature held some hearings, but the bills never made it out of committee and the new Democratic majority used its power to focus on housing and other issues.

Now, in light of the sustained protests, lawmakers are taking steps to finally address 50-a. Progressive state senators from New York City are leading the charge—including Julia Salazar of Brooklyn, Jessica Ramos of Queens, Alessandra Biaggi of the Bronx and Westchester, and Jamaal Bailey of the Bronx, whose bill, first introduced in February 2019, is the go-to for repeal advocates. They say that constituents have been calling into their offices in droves to ask that they repeal 50-a, and on Monday, a group of 85 community, labor, and criminal justice organizations signed onto a letter to the legislature demanding that it pass the repeal bill. The City reported that Democrats in the state legislature have been meeting by video to discuss their strategy, and that they may have enough votes to repeal when the legislature meets next week to address a series of police reforms. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has indicated that he would immediately sign a bill to reform the statute—but it’s not clear what he means by reform, nor if he’s on board with an outright repeal of the law.

Leading the opposition to any change to 50-a is the New York City police officer’s union, the Police Benevolent Association, which has for years stifled reform efforts with rigorous lobbying and hefty political donations. The PBA’s power could be draining, however, now that protests have mobilized public opinion against the police, even to the point where lawmakers are rejecting campaign donations from the union. The PBA argues that repealing 50-a would leave officers open to invasions of privacy. Its president, Patrick Lynch, has repeatedly asserted that a repeal would give people information to target cops at their homes—an unlikely scenario, given the New York Freedom of Information Law prohibits the release of addresses, phone numbers, and other personal information.

Repealing 50-a “would prevent the NYPD from being able to say in court that they don’t have to release disciplinary records of, for example, officer Daniel Pantaleo, who killed Eric Garner [in New York City in 2014],” Salazar told The Appeal on Sunday.

Indeed, one of the rejected 2017 cases, filed by the Legal Aid Society, was a Freedom of Information request for Pantaleo’s disciplinary records; if they weren’t leaked to the media, they likely still wouldn’t be public today. And during this week’s protests, several advocates have pointed out that, if Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin had killed George Floyd in New York, no one would know about the 18 prior complaints against him, only two of which ended in discipline.