Women Bear the Brunt of New York’s Prison Care Package Ban

New restrictions have made it harder to send food to incarcerated people. Advocates say the policy is doing disproportionate harm inside women’s prisons, and to women on the outside who often serve as caretakers.

New York’s new restrictions on prison care packages are imposing unique burdens inside women’s prisons, further straining the already tenuous connections many incarcerated people have to the outside. As New Yorkers are forced to turn to prohibitively expensive third-party vendors to send products to their loved ones, prisoners at these facilities are losing vital access to healthy food. Women in the community, who are disproportionately responsible for supporting people in both men’s and women’s prisons, are facing undue harm as well. They describe the package policy as an untenable financial burden and a threat to their relationships with loved ones inside.

Earlier this year, the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (NYSDOCCS) began rolling out the new prison package policy, which officials claimed—despite some evidence to the contrary—was necessary to prevent drugs and other contraband from entering facilities. Under the newly enacted rules, friends and family members can no longer directly send or hand-deliver food packages. They must now purchase all packages through vendors, with the exception of two non-food packages sent by mail each year.

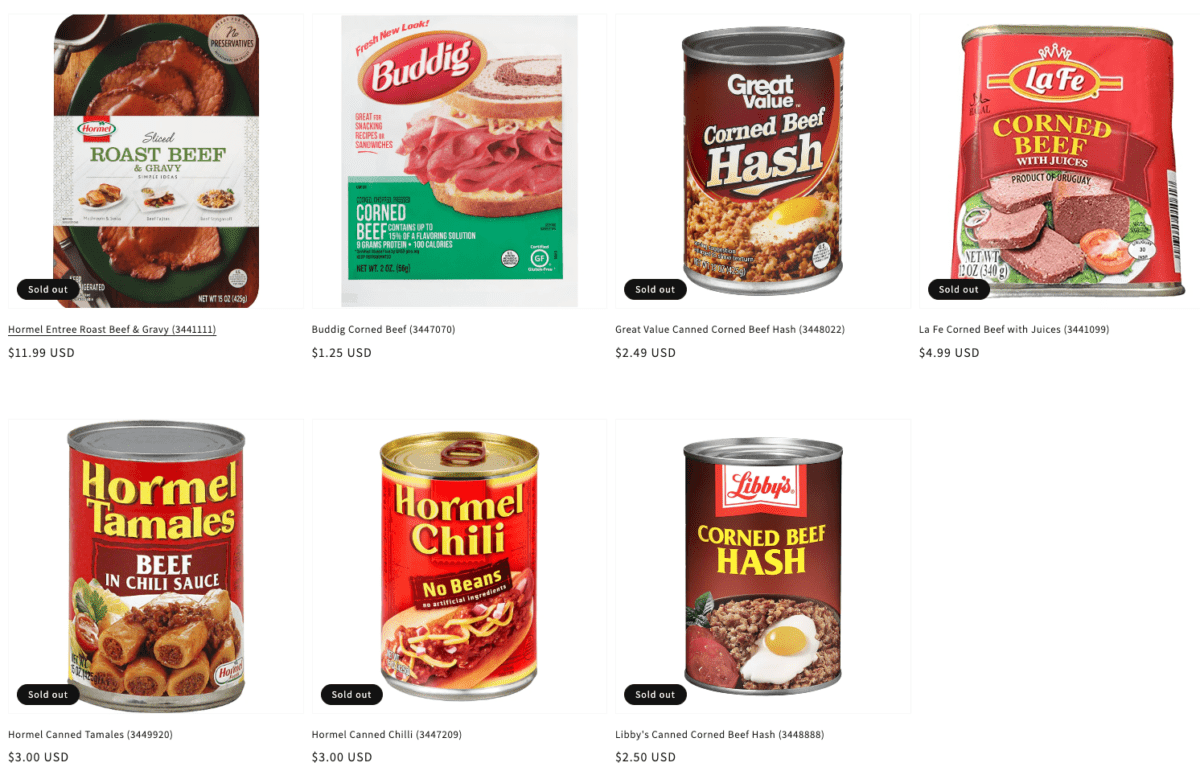

In the past, prisoners often relied on loved ones to bring or mail them fresh food, typically purchased from a grocery store. Now the entire system revolves around third-party vendors like Amazon and Walmart, or prison-specific providers like New York-based Emma’s Premium Services. The new policy has dramatically increased the cost of sending products into prisons, limited the variety of available goods, and left people to deal with large corporations that are unprepared or unwilling to abide by NYSDOCCS’s strict specifications for mailing packages. Incarcerated sources told The Appeal that very few women receive packages at all anymore and that those lucky enough to get food deliveries often share the products with other prisoners.

These restrictions on food packages threaten the health and well-being of all people in prison. But advocates say the policy is also doing disproportionate harm in women’s prisons by compounding existing inequities. People in women’s prisons already tend to have more precarious outside support systems than men, a trend that appears linked to multiple factors, including the astronomically high number of women—and other gender-expansive people housed in women’s prisons—who have experienced domestic or gender-based violence prior to their incarceration. Meanwhile, women on the outside are also bearing the brunt of the policy’s new costs and complications.

“I feel like, anytime something happens in prisons and jails, it always falls back on moms and women,” said Serena Liguori, executive director of New Hour for Women and Children–Long Island, a nonprofit that serves justice-impacted mothers in New York.

When Al-Shariyfa Robinson, who goes by Missy, was sentenced to 15 years to life in 2016, her mother Donna, 67, vowed to care for her daughter. But she was quickly struck by how difficult it was to do so. Even before the recent ban, navigating extensive NYSDOCCS rules and restrictions left her frustrated and distrustful. “I call them the Department of Corruption,” she said.

Over the summer, Missy, who has always suffered from an iron deficiency, was taken to an outside hospital for treatment, after several corrections officers expressed concerns that she looked unwell. At the time, Missy’s period had lasted for 45 days; she had lost so much blood that she needed an emergency transfusion.

Because Missy is “the property of New York State,” as Robinson put it, Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women, the prison where she’s incarcerated, never notified Robinson that her daughter was in the hospital. She found out days later, after Missy returned to the prison. Considering these constraints, Robinson found that one of the few ways she could support her daughter’s health was to provide her with nutritious food to supplement or replace the notoriously poor-quality, industrially manufactured prison mess hall food, which prisoners call “chow.” Chow is a fitting term, Robinson said in a text, because it’s “reminiscent of Dog S%$t.”

In the past, Robinson had brought Missy iron-rich foods on visits. She brought meats, and beets were “high on the menu,” Robinson said, though she also took pleasure in buying Missy her favorite snack: Entenmann’s brownie bites. But the package ban has made it impossible for Robinson to maintain this care.

Confused by the complexity of the restrictions and countless vendor websites and catalogs, Robinson initially opted to instead send Missy money for commissary, a prison store that offers snacks, packaged meals, and occasionally a limited selection of fruits and vegetables, all at a steep markup. The produce Missy bought there was often rotten and she would have to throw it away, she told her mother.

During a recent visit to see her daughter, Robinson decided she had to make a change. “I’m sitting across from her; she was starving,” Robinson told The Appeal. In October, she placed a food order with GROONO/S, a New York-based vendor. She paid $212 for around 24 pounds of food after shipping and handling, close to double what she’d paid in the past. “Half of that stuff in there was not worth $10,” Robinson said, adding that the meat she ordered was out of stock.

Still, Robinson knows Missy is fortunate to have outside support in addition to the small salary she makes from working two jobs at the prison, which amounts to about $24 a month. Shortly after Missy arrived at Bedford, she called Robinson and asked if she could support 10 other incarcerated women. “She said, ‘Mommy, they don’t have anybody to take care of them,’” Robinson recalled.

For many incarcerated people, and particularly those who are serving longer sentences, outside systems of care inevitably fade away. This is an especially pervasive problem among women, who are increasingly receiving longer sentences and may face a greater likelihood of disciplinary action while incarcerated, which can prevent them from receiving time off their sentences.

Women in prison “are not taken care of like men,” said Ethel Edwards, who was previously incarcerated at Bedford Hills and Taconic Correctional Facility. “You go to a woman’s prison on Mother’s Day, and you see how many visitors there are. You go to a men’s prison on Father’s Day, and you see how long you wait to get into the prison because the line is going around the corner.”

This lack of outside support places many women fully at the mercy of the prison system. Some may have funds to buy food at commissary, but incarcerated sources told The Appeal that the store’s already high prices have shot up in recent months, making healthy options even more unaffordable. With the new package restrictions in place, more women are being left to rely exclusively on prison meals to get by. These challenges are especially daunting for people with medical issues, said Victoria Law, a journalist, contributor to The Appeal, and author of “Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women.”

“People who are pregnant, people who are menopausal, women who are getting older who have nutritional needs that they might not have had when they were 30 or 40, are now faced with this decision of like, do I spend this money on making a phone call home to my family? Or do I try to save it up to be able to buy this thing?” said Law. “And the family has to make that same decision.”

To Liguori of New Hour, the new package restrictions are just another way for DOCCS “to make people feel desperate and anxious and depressed and sad.”

“Not having access to food that’s good for you, like mandatory for your health, over 10 to 15 years … can lead to things that will kill you,” she said. “Isn’t the punishment just supposed to be being incarcerated and losing your freedom?”

But as Robinson’s struggles to provide for her daughter demonstrate, the gendered impact of the package ban isn’t only being felt inside women’s prisons.

Around one in four women, and almost one in two Black women have a family member who is incarcerated, according to one nationwide study. Meanwhile, nearly 70 percent of women supporting a loved one in prison reported that they were also their family’s only wage-earner. The increased costs and complications associated with the package ban only make those responsibilities more taxing.

“Most Black women like myself—we end up becoming the head of the household,” Robinson said. “And we do the best we can with what we have.”

Robinson currently helps support three households, in addition to herself and Missy, and has also provided assistance to multiple incarcerated family members in the past. She described it as a matter-of-course, an inheritance that she hopes will not pass to her great-grandchildren and future generations.

“I’m making sacrifices that at my age I shouldn’t have to,” Robinson said. “This is the story of my life.”