New York’s Prison Package Ban Places New Burdens on the Incarcerated

Advocates say the policy, aimed at eliminating contraband, will harm prisoners and their loved ones by making it much harder to send fresh food and other essentials into prisons.

Twice a month, Caroline Hansen wakes at 5 a.m. to make the three-hour drive from her home in Suffolk County on Long Island to the Sullivan Correctional Facility in Fallsburg, New York, where her husband is serving a sentence of life without parole. On one of these trips, she brings a 35-pound package of food.

Hansen is well-versed in the myriad restrictions that regulate these packages. She knows that all food given to people in prison, excluding fresh produce, must be hermetically sealed. She knows to buy bread without poppy seeds, nuts without shells, and oatmeal without raisins. She also knows these restrictions are always in flux, and there is a chance she runs afoul of them. But Hansen does her best to follow the rules because she wants to maintain a more intimate connection with her husband and make sure he gets fresh food—a rarity in prison. “My husband loves avocados,” she said. “I remember the first time I brought him an avocado, he was like, ‘I haven’t had an avocado in 25 years.’”

But now, Hansen’s routine—along with her husband’s access to fresh food—stands to be completely upended. In April, the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (NYSDOCCS) implemented a new policy prohibiting all care packages containing food. Under the new rules, friends and family will only be allowed to send two non-food packages per year to their incarcerated loved ones. Those packages must be sent via the U.S. Postal Service, FedEx, or UPS, meaning people like Hansen will no longer be able to hand-deliver them. All other packages will have to be purchased through external vendors.

The pilot program has already gone into effect at eight of the 12 correctional facilities within the Wende Hub. Starting this month, the restrictions will be phased in at two hubs every other week, until all state prisons are in compliance.

The new policy, known as the Secure Vendor Program, exists in other states in various forms. It follows a failed attempt in New York in 2018 to implement a similar rule change, which was reversed after just 10 days amid intense public outcry. Since then, corrections officers have advocated for the policy’s return, arguing that it would stem the flow of drugs and other contraband into prisons, which they blame for violence and overdoses.

But advocates say the move is an extreme and unnecessary measure that will severely restrict—and for many incarcerated people, eliminate—access to fresh food in prison, exacerbating the inequities of a carceral system that seeks to monetize every interaction between incarcerated people and their loved ones. They argue that much of the contraband actually comes into prisons from guards themselves, and have characterized this as a new extractive scheme that will only benefit private companies.

“It places so much more stress on the families who are literally already hauling bags of groceries from Brooklyn on the train, just so they can get what their loved one is asking for,” said Anna Adler, one of the co-founders of the Sing Sing Family Collective, a group of family members and incarcerated individuals at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining. “It breaks down a support system.”

Under the updated policy, families and friends can order care packages from any vendor—a departure from the failed 2018 directive, which had forced people to choose from a list of six approved vendors. Although these more open-ended guidelines carry their own complications, they’re a positive step that wouldn’t have happened without advocacy in New York, said Bianca Tylek, founder and executive director of Worth Rises, a nonprofit that successfully organized opposition to the 2018 directive. Still, Tylek sees the new package policy as the latest addition to a robust system designed to squeeze money out of incarcerated people and their families.

“Privatization has been really aggressive since the 1980s,” she said. “It feels like every year they come up with something new.”

The package program itself is the product of advocacy, in this case from the New York State Correctional Officers & Police Benevolent Association, which has played a key role in rolling back criminal justice reforms in Albany. Citing incidents of violence and overdose in prisons, members of the Prison Violence Task Force (PVTF)—a new group formed within NYSDOCCS in 2021—began pushing for the policy this year. They have argued that packages coming from third-party vendors would be far less likely to contain contraband, like weapons or drugs.

Advocates like Wilfredo Laracuente of the Sing Sing Family Collective believe that the policy is more about retaliation than security. He pointed to the recent implementation of the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term (HALT) Solitary Confinement Act, which limits the use of solitary confinement in New York prisons and jails, and noted that corrections officers are aggressively pushing for its repeal. “Now they can’t [use solitary] as a punitive punishment, they’re going to weaponize other things,” said Laracuente, who served 20 years at Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

Currently and formerly incarcerated individuals have expressed their own concerns about violence and drugs in New York prisons, but they’re worried that the new package policy will only make these problems worse. Amy Peterson, who works with Sweet Freedom Farm, a farming collective in Germantown that distributes fresh food to people in prison, recently spoke with a friend who serves on the Incarcerated Liaison Committee (ILC) at Eastern Correctional Facility. “You’re taking away resources from people,” Peterson recalled her friend telling her. “And when people don’t have what they need, bad things happen.”

While there is little disagreement that family and friends pass some contraband into prisons, advocates say they are being scapegoated for a problem widely believed to stem primarily from prison employees.

“We all know that most of the contraband comes in through the staff,” said Barbara Allan, who has been running peer support groups for families with loved ones in prison for over 50 years. “We’ve always known it.”

Indeed, official data suggests that drug use in prison continued and perhaps increased during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, even as visitation was halted and most families were forced to turn to vendors to send packages. Although New York prisons were closed or severely restricted to visitors between March 2020 and December 2020, NYSDOCCS reported that overdoses rose from 2019 to 2020, as indicated by an increase in officer use of the overdose reversal drug Narcan.

In the view of Michael Capers, an advocate who was recently released from prison after serving 12 years, any policy that seeks only to address the supply of drugs—however ineffectively—will fail to address the root of the problem. He described current prison programs for drug abuse, anger, and grief as inadequate and perversely, a privilege awarded for good behavior. If you struggle with substance abuse in prison, “you’re looked at as part of the problem for having this addiction and you’re penalized,” Capers said. “So if you happen to relapse while you’re in this drug program, you get removed from it.”

Capers, who is studying to become a nutritionist, also raised concern about the new policy’s effect on the health and well-being of the incarcerated, who already suffer adverse health consequences due to the poor quality of prison food.

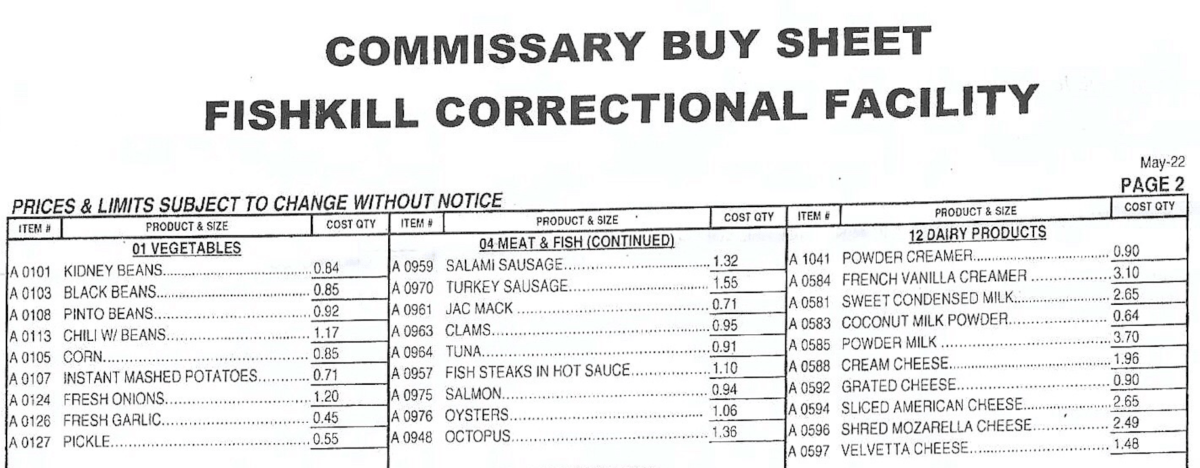

Outside of Hansen’s packages, her husband says his diet consists largely of white bread, imitation chicken patties, and canned vegetables. The portions are small and contain an alarming lack of nutrients—if they aren’t entirely spoiled or contaminated—and the monotony of eating the same thing for years on end can feel like its own form for punishment. Prisoners who have enough money can buy food at the commissary, but with a menu that consists mostly of packaged goods, it doesn’t provide a balanced diet.

By further tying a prisoner’s access to fresh food to their financial resources, the new package policy threatens to entrench existing health disparities behind bars, especially among Black and low-income people who are highly overrepresented in New York’s prison system. “What’s getting lost is the food system’s impact on the Black community,” Capers said, noting that effects of incarceration on people’s health and wealth extend beyond the individual, draining entire communities.

But if you view incarceration as a mode of extraction, all of this is by design, said Jennifer Fecu, an advocate who served 20 years at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. “The state of life we’re in, [even] if it’s near death, it doesn’t matter, as long as we’re generating funds,” she said. “Everyone is considered a body, and people inside really realize it.”