New York City Laundry Workers Struggle in the Face of COVID-19

Workers report facing a difficult choice between earning a living and feeling safe and healthy at their job.

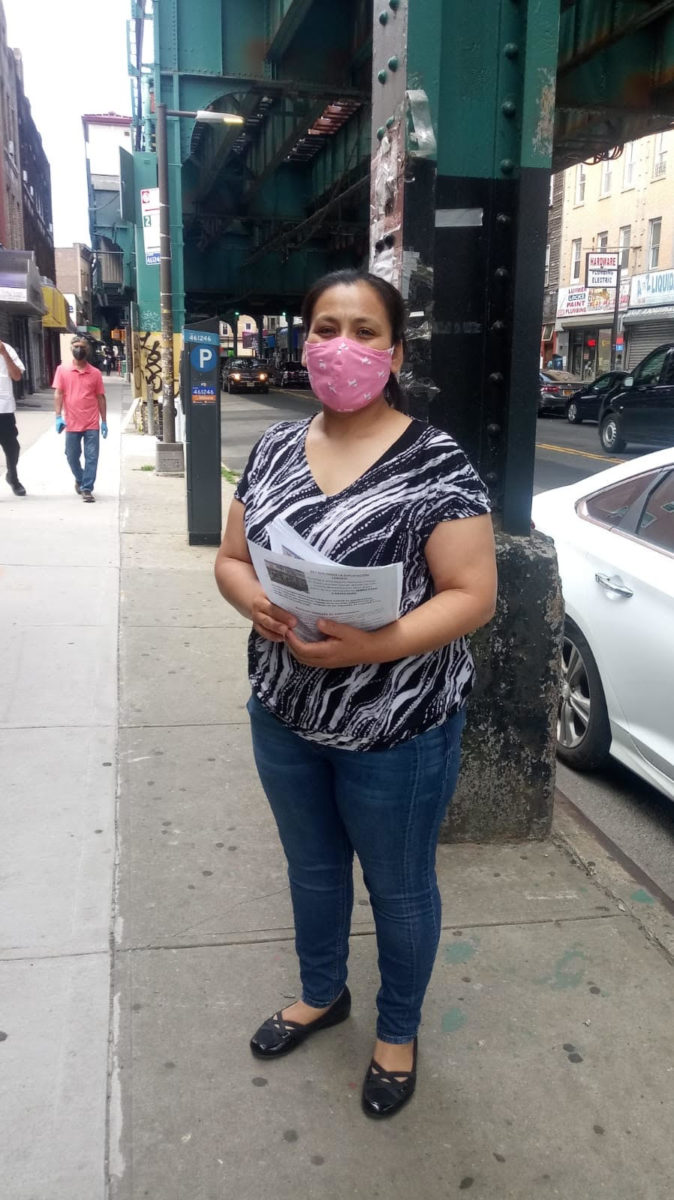

It has been a difficult few months for Beatriz Ramirez since she was fired from her job at New Giant Launder Center after three years on the job. The laundromat in Queens’s Richmond Hill neighborhood supplemented her husband’s income and helped keep the lights on as well as food on the table for them and their five daughters.

The job was not easy. Ramirez, an immigrant from Mexico, routinely worked 56 hours a week for barely $6.50 an hour—well below New York State’s minimum wage—with no overtime. And according to Ramirez, despite the COVID-19 pandemic killing Black and Latinx residents at twice the rate of white residents in New York City, her employers, James and Grace Park, refused to supply protective equipment such as masks and gloves; if employees asked for them, Ramirez said, “the boss would verbally abuse us” by calling the employees rude names. Neither owner responded to The Appeal’s requests for comment.

In April, fed up with her unsafe work conditions, Ramirez sued her employers for wage theft with the help of the Laundry Workers Center, a membership-based organization that advocates for improved living and working conditions of low-wage laundry workers. “Laundry workers should have better salaries and at least make the minimum wage to all the workers in the city,” Ramirez said in a phone interview. Shortly after she filed suit, she was fired.

Ramirez’s story is a glimpse into an industry fraught with abuse and exploitation. In the New York City metropolitan area, the commercial laundry industry employs over 17,000 laundry and dry-cleaning workers who on average annually earn $27,590. The industry is dependent on a large percentage of Latinx women as well as a large proportion of undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Given their legal status, immigrant workers are particularly vulnerable to employer abuse such as wage theft and harassment, which are common. The COVID-19 crisis has magnified that abuse.

“The pandemic has brought to light the unacceptable conditions in which the workers operate, exposing themselves to this dangerous virus while still working for less than minimum wage,” Lina Stillman, a labor lawyer representing Ramirez, wrote in an email. “The employers continue to take advantage of these laundry workers by making them work 11 to 14 hours per day, sometimes during the graveyard shift.”

“Even before the coronavirus, conditions of laundromat workers were bad,” Rosanna Rodríguez, co-executive director of the Laundry Workers Center, said in a phone interview. “In this industry, there are so many workers who don’t even get the minimum wage and work overtime without getting paid for it.”

Rodríguez says many of her organization’s members have complained about lack of safety equipment such as masks and gloves. Since the outbreak occurred in New York, nearly 80 organization members have come down with symptoms of COVID-19, she said. Yet, with 45 percent of laundry workers without sick leave, many continue to work.

“Right now, we have a lot of workers getting sick with symptoms of the coronavirus, but they don’t have the protection that they need to do the work,” says Rodríguez. “With the outbreak it’s clear that all workers need paid sick leave so they can take care of themselves and their families.”

For almost two weeks, Sandra continued to work in a laundromat in Manhattan despite being sick with symptoms consistent with COVID-19. (The Appeal is not using her real name, as she is an undocumented immigrant.) She was afraid to go to the hospital and get tested, even though her head felt like it was being battered by a hammer. According to Sandra, the laundromat had no ventilation and was constantly crowded with people. Despite asking on several occasions, her employer refused to provide workers protective equipment and enforce social distancing. When the pain became unbearable, Sandra asked her supervisor if she could go home. According to Sandra, the supervisor told her to take some Tylenol and get back to work.

“My headache got so bad I could barely think,” Sandra said. “In fact I would be crying in pain. All they told me was to take pills and wait until another worker would come in to replace me. How can I work when I’m in pain?” But without paid sick leave, she couldn’t afford to lose the income that was supporting herself and four children. She continued to work. To alleviate the harsh conditions workers like Sandra endure, Rodríguez is calling on the city and the state to take action.

“We want the city to create an economic relief fund for all undocumented workers,” said Rodríguez.

On May 25, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo announced plans by state and local governments to provide death benefits for the families of essential workers who died from COVID-19. Deemed essential by the governor, laundry workers would be eligible for the funds. He also called on the federal government to provide hazard pay for essential workers.

Prior to the governor’s announcement, in April, New York City Councilmembers Ben Kallos, Brad Lander, and Speaker Corey Johnson introduced legislation that would take steps towards protecting laundry workers like Ramirez and Sandra from unjust termination. The bill would require employers to provide “progressive discipline and a ‘just cause’ within a week of termination.” Under the bill, essential employees would be able to recover back pay and employers would be required to pay a fine of up to $2,500 per violation.

“No one should lose their job simply for asking for protective equipment during a pandemic,” Kallos said in a statement. “Our city’s essential workers including people working in the laundry industry deserve to be treated with respect, complete with job protections for putting their lives on the line day in and day out.”

Three months into the pandemic, the bill and a package of other pandemic protections for workers have been held up in committee. Meanwhile, Ramirez’s situation is still precarious. In May, she said she was able to reach a verbal settlement with her boss: If the Parks agreed to provide safety gear, pay back-wages and rehire her, she would drop the suit. However, Ramirez said Park has reneged on the agreement to rehire her, now only agreeing to pay the back wages. With the Laundry Workers Center’s assistance, Ramirez continues to fight for herself and other workers, but understands that without government help, many workers like her are still facing daunting times ahead.

“Workers like me are always in danger of losing our jobs or getting sick,” said Ramirez. “The city needs to help us before more of us get sick or get others sick.”