A New Mexico Man Accused a Deputy of ‘Gestapo’-like Training. Then He Was Arrested.

In Valencia County, a sheriff’s deputy who once faced allegations of excessive force in Albuquerque is accused of assaulting an elderly man.

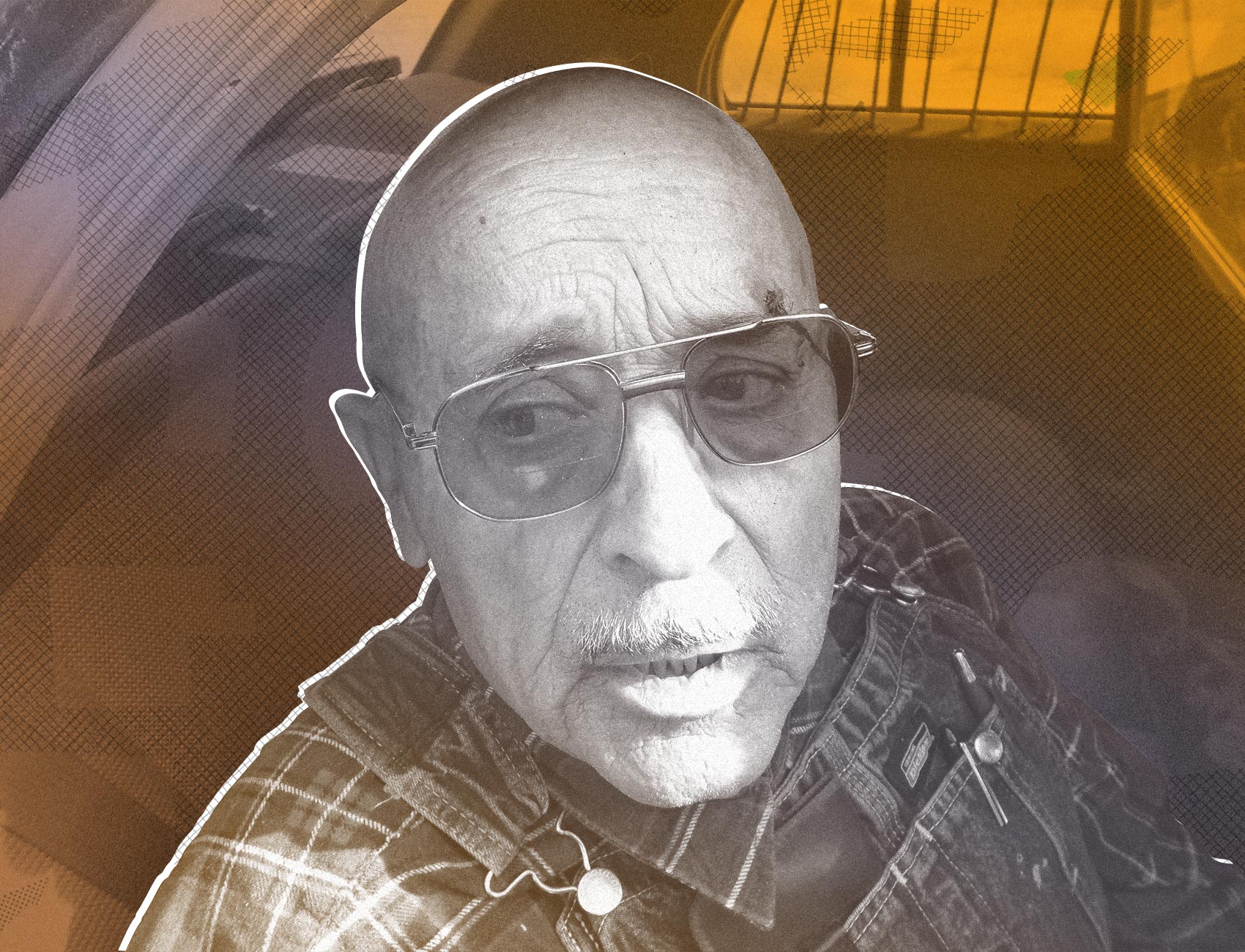

Albert Carrillo was on his way to an appointment on Jan. 9, 2018, when a Valencia County sheriff’s deputy stopped him in Belen, New Mexico. Deputy Cole Knight pulled Carrillo over and told him that he was driving too slow and swerving, and that the license plate on his pickup truck was obstructed by a metal trailer hitch.

Carrillo, 74, had gotten out of his truck and confronted Knight. Knight later claimed in a police report that Carrillo approached him with his fists clenched. Knight was not wearing a body camera and his vehicle was not equipped with a dashboard camera, so no video exists of the interaction. But audio was captured on Knight’s belt tape, a device similar to a body camera but which only records audio.

“I need you to understand, Mr. Carrillo, that you’re pushing the limits of my patience,” Knight said. “Is there something going on with you?”

“Yes, you people,” Carrillo replied. “You’re being trained like a Gestapo son of a bitches.”

Carrillo explained to Knight that he was trying to get to a doctor’s appointment. In audio of the incident, Carrillo sounds frustrated with the traffic stop and is resistant to Knight’s request, but does not raise his voice.

Knight told Carrillo that he felt threatened by his “attitude and clenched fists” to which Carrillo responded, “Oh.” Knight then placed Carrillo under arrest, but provided no legal justification or explanation for it.

When Knight placed Carrillo in his patrol vehicle, he bumped his head on the vehicle, causing a gash.

“You know what?” Knight said. “Now, you have another reason not to like us.”

In late July, Albuquerque attorney Kenneth Stalter filed a civil rights lawsuit on behalf of Carrillo in Valencia County District Court. He told The Appeal that Carrillo’s “Gestapo” comment was “imprudent but still freedom of speech…One of these people is cloaked with the authority of the state, has the weapons, has the backup and has the training to deal with these situations. It’s incumbent on them to de-escalate and if there’s been no crime or arrestable offense, to refrain from arresting somebody.”

The lawsuit alleges Knight falsely arrested Carrillo and violated Carrillo’s free speech rights.

Stalter said that Carrillo’s “Gestapo” remark triggered the arrest. “At that point, the only allegation is that there was a traffic violation for going too slow and potentially an obstructed license plate,” Stalter said. “There is nothing that was alleged … that Mr. Carrillo committed an arrestable offense.”

According to Stalter, Knight charged Carrillo with felony battery of a police officer for allegedly spitting on him as he was being placed in the patrol vehicle. Carrillo vigorously denied spitting on Knight. In April 2018, Carrillo pleaded no contest to misdemeanor disorderly conduct and was sentenced to 182 days of unsupervised probation.

Audio of the incident appears to contradict Knight’s account.

In his report, Knight claims Carrillo said, “You are my fucking problem, you Gestapo piece of shit.” But Carrillo actually said “you’re being trained like a Gestapo son of a bitches.” Knight also wrote in his report that he requested Carrillo’s driver’s license—but that is not captured on the audio. And Knight wrote that Carrillo pretended to hand Knight his driver’s license but pulled it away and then pushed it into his face. The audio provides no evidence of that interaction.

Prior to joining the Valencia County Sheriff’s Department, Knight worked for Albuquerque police. In 2012, Knight was a defendant in a federal civil rights lawsuit alleging that he falsely arrested and assisted in assaulting a man named Michael Bernal outside his home. The lawsuit alleged that in 2010, Knight and another officer, Benjamin Melendrez, went to Bernal’s home after receiving a complaint that he had been driving while intoxicated.

Bernal was inside his home when Knight and Melendrez arrived, and he stepped outside to speak with them.

According to the lawsuit, Bernal asked Knight if he was under arrest as Knight threw him to the ground. Melendrez then allegedly beat Bernal, who suffered multiple injuries, including a broken wrist. The case was settled in 2013; its terms were not disclosed.

The Albuquerque Police Department has been repeatedly accused of excessive force and corruption. Between 2006 and 2011, the city’s police shot 38 people, 19 of whom died. In 2011, they shot and killed a 27-year-old schizophrenic man. The local police union also once gave cash to officers who shot and killed a person to help them “decompress.”

In 2015, then Bernalillo County District Attorney Kari Brandenburg charged two Albuquerque officers with murder in the 2014 shooting death of James Boyd, a homeless man with schizophrenia. In October 2016, a Bernalillo County jury ultimately deadlocked on the charges against the officers. In 2017, newly elected District Attorney Raúl Torrez decided not to seek a retrial.

In 2014, Boyd’s family sued the Albuquerque police department. In 2015, Albuquerque agreed to pay the family $5 million to settle the lawsuit.

That same year, the U.S. Department of Justice concluded an investigation into the Albuquerque police. As a result of that investigation, the department agreed to make several changes including better reporting of use of force incidents, more oversight, new guidelines for uses of force and increased training for officers.

Knight “has a kind of tortured history with prior agencies,” Carrillo attorney Stalter said.

Knight resigned from the Albuquerque Police Department in 2017, claiming in his letter of resignation that the policies of the department became a “direct conflict with my personality.” He joined the Valencia County Sheriff’s Department later that year.

When The Appeal contacted the sheriff’s department for comment on Carrillo’s case, a representative directed the request to the county manager’s office. Citing ongoing litigation, a representative from the office declined to comment when asked if Knight was disciplined in the Carrillo incident or if he is on active duty.

“It’s our case that [Carrillo’s arrest] was pure retaliation for protected speech,” Stalter said. “[What Carrillo said is] not something all of us would say but freedom of speech exists to protect those things that may not be wise to say, or many people may not agree with or find offensive.”