New DOJ Report Demonstrates Stunning Disingenuity on Cases Involving Sexual Exploitation of Children

A recent bombshell report from the Department of Justice claims that the number of people prosecuted in federal court for commercial sexual exploitation of children roughly doubled between 2004 and 2013. The title of the report from the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Prosecution of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Cases, 2004–2013, conjures the specter of […]

A recent bombshell report from the Department of Justice claims that the number of people prosecuted in federal court for commercial sexual exploitation of children roughly doubled between 2004 and 2013.

The title of the report from the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Prosecution of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Cases, 2004–2013, conjures the specter of children being forced into sexual slavery. The titling and framing of the report leaves a casual reader with the impression that more and more children are falling victim to commercial sex offenses — such as sex trafficking — and that DOJ has placed a high priority on prosecuting these offenses.

The actual data contained within the report itself, however, merits no such dramatic conclusion. The DOJ defines the phrase the “commercial sexual exploitation of children” (CSEC) as involving “crimes of a sexual nature committed against juvenile victims for financial or other economic reasons,” the obvious implication being that these “CSEC” defendants are directly involved in the trafficking of children for sexual purposes. However, according to the BJS’ own data, the vast majority of the defendants charged with CSEC offenses were accused, not of producing of child pornography or of child sex trafficking, but of consuming child pornography, including images of cartoon obscenity:

Prosecutions related to the possession, receipt, or distribution of child pornography increased by 91% … Of the 21,887 defendants in cases led in U.S. district court with a CSEC charge from 2004 to 2013, 80% of defendants were charged with possession, receipt, or distribution of child pornography.

Lumping the terms “possession, receipt, or distribution” of child pornography together is another bit of sophistry. While the term distribution obviously lends itself to economic arguments, in the overwhelming majority of cases it means something much less sinister: 73% of federal child porn distribution cases involve little more than a defendant using a peer-to-peer network to download child pornography, with “distribution” being baked in to how peer-to-peer networks operate. They are offenses which are generally committed as a result of technological illiteracy, as opposed to mercenary motive. The remaining roughly 27% of distribution cases typically involve defendants swapping illicit images directly with one another, though without any money changing hands. For example in 2010, exactly zero of the distribution cases pressed at the federal level involved commercial distribution.

Prosecution of non-production, non-economic child pornography cases nearly doubled in federal court over the time period in question in the DOJ report, yet also comprise the vast majority of offenses that the DOJ is characterizing as offenses committed against minors for “financial or other economic reasons.” Carissa Hessick is law professor at the University of North Carolina and expert on federal sentencing and child pornography law. She told In Justice Today that while possession of child pornography is a serious crime,

“DOJ’s decision to lump these crimes together is so poorly explained, one worries that it was done, perhaps in part, to create the appearance that the Department of Justice has been more active in prosecuting cases involving the physical molestation of children, such as production of child pornography and sex trafficking…The numbers in this report would look far different if they excluded child pornography possession cases.”

The growth in these types of child pornography prosecutions is not necessarily indicative of an increase in rates of offending. Rather, it is more likely the result of law enforcement’s ability to secure confessions and convictions with relatively little effort. In the vast majority of these cases, investigators monitor peer-to-peer networks for hash values of images that are known to be child pornography, serve administrative subpoenas on service providers for records associated with those IP addresses, and knock on front doors with search warrants. Defenses are usually slim to none. Guilty pleas are exceedingly common: The BJS data reveals that 92.5% of defendants prosecuted in federal court for possession, receipt, or distribution of child pornography pled guilty.

Including such defendants under the banner of “CSEC” is sloppy at best and disingenuous at worst. While the DOJ’s commitment to battling commercial sexual exploitation of children is admirable, their framing and presentation of the data as implication of an epidemic is at odds with the numbers themselves.

Underscoring the need for clarity and objectivity is the fact that defendants prosecuted for non-production child pornography offenses are amongst the most harshly punished defendants in all of the federal system. The report indicates that they are the least likely of all federal defendants to be given non-custodial sentences, even over and above violent and weapon offenses, and that:

Prison sentences imposed on defendants convicted of CSEC offenses were among the longest in the federal justice system. The mean prison sentence imposed on convicted CSEC defendants increased by 99% from 2004 to 2013, from 70 to 139 months.

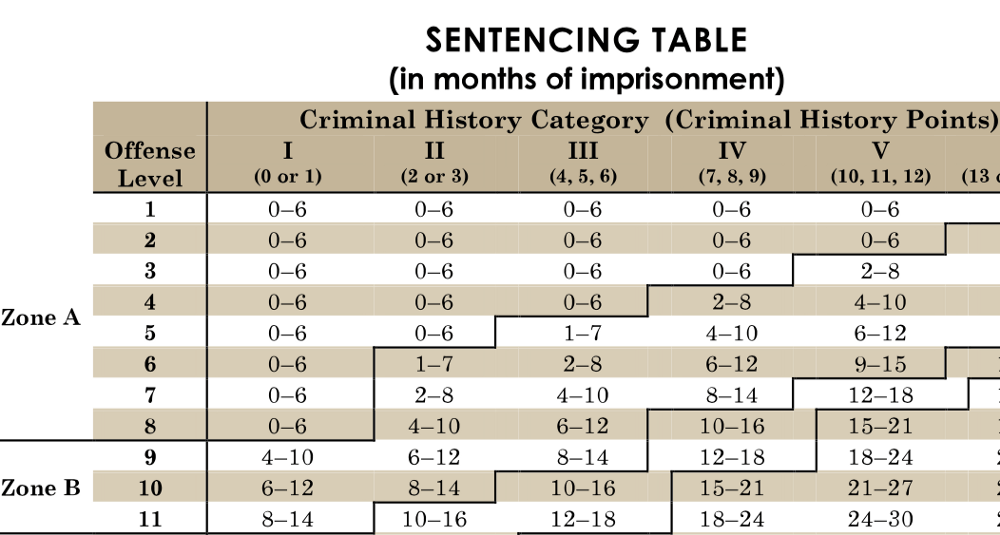

Sentences to the north of a decade are routine for CSEC defendants by virtue of the United States Sentencing Guidelines. These provide a recommended “range” in months of imprisonment based on both the severity of an offense and a person’s criminal history. Offenses, depending on specific characteristics of how they are committed, can receive enhancements that result in lengthier terms of imprisonment.

There are a number of significant sentencing enhancements for child pornography cases which are routinely applied. These may have held some rough logic in an era before Google, but they make little sense now. Use of a computer? Enhancement. More than ten images? Enhancement. Distribution, even unintentional distribution, as discussed above? Enhancement. More than 10 images (note that a video file, regardless of length, is counted as 75 images)? Enhancement. Sentence enhancements are piled on such that, even for those individuals with no criminal record and no evidence they sexually assaulted a child, the recommended sentences can easily dwarf the statutorymaximum sentences.

No other class of offense in the federal system (or, indeed, in many states) is characterized by such extreme sentences. As courts have noted, there is virtually no empirical or reasoned bases for any of these enhancements beyond naked revulsion and desire for retribution. Some scholars have suggested that such severe punishments represent punishment by proxy. In other words, they are intended to obscure and compensate for the failure of law enforcement to investigate and prosecute actual cases of child sexual trafficking and commercial exploitation. In seeking to justify such draconian punishments even for “end users,” prosecutors and others (including courts) have advanced a market theory — that even possession of such images drives a market for child pornography. The United States Sentencing Commission, in a 2012 report to Congress, noted that such arguments are without empirical support. Notably, similar arguments were made in support of harsh treatment of drug addicts in the 1970’s and 80’s as a way of winning the war on drugs.

Whatever the underlying rationale, the draconian nature of these sentences has attracted attention and push back in recent years, including from an extremely unlikely group: federal judges, some of whom are recognizing the inherent unfairness of enhancements for these types of offenses, and beginning to impose sentences far more lenient than those recommended by the guidelines.

Equating garden variety child pornography defendants with child sex traffickers is an abdication of reason and rationality. Unfortunately, the DOJ has not signaled any intention of reversing course. Rather, if the trends in the report are any indication, it appears to be accelerating the use of what might justifiably be described as a prosecutorial machine that crushes defendants in child pornography possession cases, while failing to even charge far more culpable defendants.