“Murder Every Day but the Spotlight on Bike Life”: Amid 343 Homicides, Baltimore Police Crack Down on Dirt Bikes

On January 5th, Baltimore Police Sergeant Wayne Jenkins entered a guilty plea in federal court on an array of charges such as racketeering, conspiracy, and robbery. Sergeant Jenkins is just one of eight indicted members of the Gun Trace Task Force (GTTF), a specialized unit focused on getting guns off the streets. The list of crimes Jenkins […]

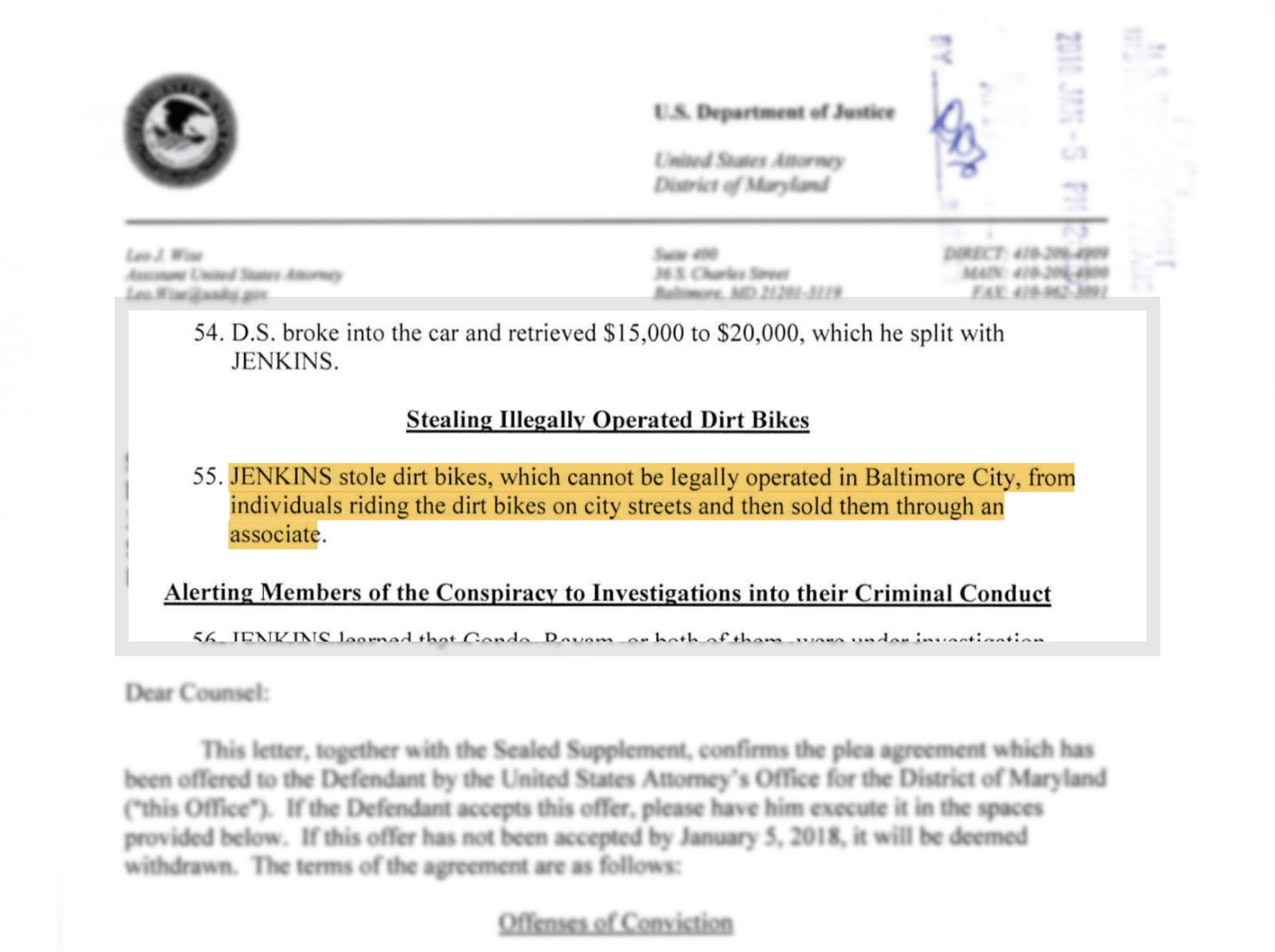

On January 5th, Baltimore Police Sergeant Wayne Jenkins entered a guilty plea in federal court on an array of charges such as racketeering, conspiracy, and robbery. Sergeant Jenkins is just one of eight indicted members of the Gun Trace Task Force (GTTF), a specialized unit focused on getting guns off the streets. The list of crimes Jenkins committed while purportedly protecting law and order for the people of Baltimore included drug sales, illegally stealing cash from people detained in his custody — and stealing dirt bikes. According to local activists, police officers such as Jenkins stole and sold dirt bikes over the past few years taking advantage of a much-touted crackdown on dirt bikes in Baltimore.

The decades-old tradition of illegal street biking — known as “bike life” — is aggressively targeted by police around the country, who have been using tactics against bikers that parallel the very same tactics used in the devastating loop of the drug war: arrest, confiscate, charge, repeat. Jenkins’ guilty plea verifies what the illegal street biking community has long accused cops of doing: Chasing them, terrorizing them, and even stealing their dirt bikes, all under the guise of promoting law and order.

New-Style Broken Windows Policing

Crackdowns on dirt bikes — and four-wheel All-terrain vehicles (ATVs) connected to the street riding scene — are a staple of broken windows-style policing in Baltimore, Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and New York, where they cannot be legally operated on city streets.

In May of 2016, then-NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton staged a press conference in Brooklyn where he gleefully watched as a pair of bulldozers crushed 69 dirt bikes seized by the police. “These bikes and riders are a menace,” Bratton proclaimed. “And I would, without a doubt, say we crushed it.” The NYPD even tweeted out Bratton’s comments on its twitter account with the hashtag, #UseItAndLoseIt. And in Philadelphia, police arrested rapper Meek Mill for popping wheelies on a dirt bike in New York City; the arrest was one of several that led a judge to recently sentence him to two to four years in prison for violating his probation.

But Baltimore bikers and advocates say that they are a scapegoat for the city’s larger problems. “The confiscation of dirt bikes is anti-black and anti-poor,” explains ShaiVaughn Crawley, a local activist. Dirt bikes, brash and loud, and dirt bikers, mostly young and black, are a convenient target for P.R.-savvy police and politicians — who offer up evidence of black men committing minor noise ordinances and moving violations as evidence of a city out of control and in need of more policing.

More broadly, dirt bikers are, quite simply, a threat to the status quo. In Baltimore, a profoundly segregated city, dirt bikers offer a tangible glimpse of rebellion and freedom; their bikes blur long-established borders between neighborhoods, rich and poor, white and black. As a 2015 Gawker piece on dirt biking observed, “the bikers…have challenged [Baltimore’s] systemic separation simply by riding through it.”

Whose Safety?

When arguing that dirt biking must be punished harshly, police departments around the country attempt to connect the activity — which sits somewhere between hobby, sport, protest, and postmodern performance art — to more serious crimes. Baltimore is no exception. In July 2016, Baltimore police officially announced a Dirt Bike Violators Taskforce “to address the ongoing concerns and dangers associated with dirt bikes.” At the press conference (the one where Commissioner Davis called dirt bikers “gun toting criminals”), police showed police helicopter footage of a dirt biker they said could be seen wiping fingerprints off of ammunition and then putting the bullets into a gun.

But dirt bikers say the greatest public safety threat comes not from them but from the police. “No chase” policies in Baltimore, Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and New York should prevent police from engaging in high-speed pursuits with dirt bikes in their vehicles. But police frequently chase dirt bikes — both in cars or overhead by helicopter — leading to accidents and even deaths. In Nov. 2016, a video circulated online that showed D.C. police in an SUV chasing an ATV rider, crossing the yellow line to get next to the rider, and then pepper-spraying him. In June of 2016, a confrontation between a Philadelphia police officer and a dirt biker ended with dirt biker David Jones shot in the back and killed by Officer Ryan Pownall. Police say they stopped him for erratic driving and searched him; then he escaped, reached for his waistband, and was shot. (Philadelphia Magazine spoke to a witness who disputed this version of events.)

In 2012, two high-profile dirt bike deaths occurred in New York: Eddie Fernandez, killed when police car hit his bike and sent him into a pole; and Ronald Herrera, hit from the back by police car in an accident that also left Herrera’s passenger paralyzed.

In Nov. 2016, a video shot by a Philadelphia dirt biker shows dirt bikers wildly weaving in and out of traffic and disobeying traffic laws, but also a police SUV chasing the dirt bike; not long after the video was shot, a dirt biker ran into a cop car.

When I covered the start of the police crackdown on dirt biking for Baltimore City Paper in the summer and fall of 2015, I frequently witnessed police chasing dirt bikers and was present at the aftermath of three collisions. I also heard many stories from bikers about being bumped by cops. Bikers even described cops driving up and tasing them.

In one incident I covered, on Aug. 30, 2015, a marked law enforcement car struck a dirt biker after he allegedly stopped his bike in the street; then police arrested him, claiming the bike was stolen. Multiple eyewitnesses disputed the official account of the accident — they said the dirt biker was chased and struck by the cop car — and the police later retracted a claim that the bike was stolen. In the end the dirt biker’s stolen property charge was dropped but traffic charges remained.

The City Responds

Since the GTTF scandal, the Baltimore City Council has called attention to police corruption, and, after GTTF member Jenkins admitted to stealing dirt bikes, to the Baltimore Police’s dirt bike crackdown. Today, there will be a public meeting held by City Council for “Increased Transparency About Police-Seized Property,” and along with a discussion of guns, drugs, cash taken by cops “over the last 5 years,” it also demands a “full account” of dirt bikes seized by police.

But activists are skeptical that the City Council will meaningfully address the over-policing of anything, especially dirt bikers.

“I have zero confidence in the Judiciary and Legislative Investigations committee to properly hold BPD accountable, and the meeting will be yet another dog and pony show, something we know all too well in this city,” says Baltimore activist Crawley. “Wheelie Wayne should not have had to pay $25k in bail money. The crackdown of dirt bikes is counter-productive, facetious, predatory and a waste of time.”

Crawley is referring to one of Baltimore’s most popular dirt bikers (along with Meek Mill affiliate Chino Braxton), DaWayne Davis AKA “Wheelie Wayne,” who was arrested in Aug. 2016 and hit with 15 charges connected to manually removing serial numbers, theft and allegedly running a “chop shop.” Numerous bikes and bike parts were found in his West Baltimore home, as well as engines with serial numbers filed off, a damning detail for sure, though a hard-nosed fix if your hobby is illegal and you’re well aware that police chase young black riders — his mentees.

Dirt bikers in the city say Wayne was targeted due to his popularity (weeks before his arrest, he appeared on a since-deleted police list of “dirt bike violators”). In Sept. 2017, Wayne agreed to serve 48 hours of community service and forfeited claims to seized dirt bikes and parts.

If Wayne had it his way, dirt biking wouldn’t be underground. He has been a longtime advocate of a legal dirt bike track. He is joined by others including B-360, a Baltimore non-profit that builds on young people’s dirt bike skills and teaches them engineering through dirt bike repair. But like so many non-carceral dirt bike solutions, it remains grassroots.

“The track would take care of public safety,” activist PFK Boom, who also supports a dirt bike track in Baltimore, told me in 2015. He recommended incentives such as additional time on the track for good grades and ticketed events where residents could gather and watch dirt bikers pop wheelies.

But for now, the track remains a pipe dream; bikers haven’t succeeded in breaking ground on public tracks in other cities. (A more modest “bike life” hub, Cleveland, nearly got a public dirt-bike track off the ground — until residents said they didn’t want the track in their neighborhood.) Meanwhile, dirt bikers think that Baltimore’s focus on bikers will take away from it actually focusing on public safety, especially in high crime cities such as theirs which had a record 343 homicides in 2017.

“Murder every day,” read a popular t-shirt designed by the dirt bikers depicting a police helicopter shining a light on a biker, “But the spotlight on bike life.”