How Missouri’s ‘Felony Murder’ Law Traps People for Defending Themselves

An investigation by The Appeal and the Yale Investigative Reporting Lab reveals how prosecutors use the state’s felony murder statute to imprison people who say they acted in self-defense. The majority of those convicted under the law since 2010 are Black. “I had to take the plea because they’re using this law to get people to stay locked up,” one man said.

This piece was published in partnership with the Yale Investigative Reporting Lab.

Technically speaking, Antonio Meanus wasn’t supposed to own the gun he had stashed in his pants on Oct. 7, 2021. But he didn’t believe he had much of a choice.

Earlier that day in Springfield, Missouri, Meanus, a tall, 30-year-old man with a goatee and shoulder-length dreadlocks, had gotten a call from a man named Raquan White, the son of his former boss. White said he was in a financial bind. He was going to come up short on his next rent payment and wanted to sell an iPhone to a 17-year-old named I’Shon Dunham. But White had dealt with Dunham in the past and said that he “didn’t feel trustworthy.” So Meanus says White asked him to come along to make sure Dunham didn’t rob him.

Meanus, who had grown up in some of the roughest areas of St. Louis, told White that the whole thing was a bad idea and offered to just give him some money. But White insisted on going. Not one to abandon a friend, Meanus got in the car.

It had been an unusually warm fall day for the city’s 170,000 residents. About halfway through the ride to the meetup point, Meanus again tried to convince White to go home instead.

“I said, ‘This don’t sound right,’” Meanus told The Appeal in a phone interview from the state’s Crossroads Correctional Center. “Let’s just turn around and go back.” White assured him it would be fine and kept driving.

They eventually reached a two-story apartment building on 422 East Norton Road. Newly planted trees dotted the lawn around the parking lot. Dunham and a stranger emerged from the red brick apartment building. The stranger’s hand was tucked under his shirt. Dunham, a slender teenager with big eyes, a wide smile, and a peach-fuzz beard, hopped into the front seat and asked for the iPhone. But White first demanded to know what the uninvited guest was doing there.

“He cool,” Dunham said.

Dunham then lunged forward, tried to grab the iPhone, and began grappling with White in the front seat. After a brief struggle, Dunham wordlessly pulled out a gun and pointed it at White’s head.

Meanus panicked. He believed that both he and White would be killed. So he pulled out his gun and shot Dunham, killing him.

Distressed, Meanus called the police to report what had happened. He knew he couldn’t have done anything else in the circumstances. He didn’t know, however, that a single state law had already taken away his right to save himself.

Eight months later, in July 2022, Meanus sat in the correctional center in Cameron, Missouri. Dalton Minnick, his best friend, was visiting him. The Greene County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office had charged Meanus with second-degree felony murder and unlawful possession of a firearm. The state’s final plea offer was 12 years in prison. If Meanus risked a trial and lost, the sentence could soar to 30 years—or life.

Meanus said he wasn’t worried. He knew he’d acted in self-defense. For months, Meanus said, he believed a jury would see it, too. Minnick agreed.

“If it was me,” Minnick said, “I would go to trial.”

But then Greene County public defender Christopher Hatley, who had been assigned to Meanus’ case, sat Meanus down and gave him the worst news he said he’d ever received.

Even though Meanus had believed he would die that afternoon if he didn’t shoot, Hatley said his self-defense claim didn’t matter. Instead, he’d be tried under Missouri’s controversial felony-murder law, which allows prosecutors to charge people with murder if, while they are committing a felony such as a robbery or assault, someone dies or is killed by a third party.

The terms of the law ensured that Meanus was as good as convicted.

Missouri is one of only four states where there are no limits on which felonies can trigger a felony-murder charge, and, once prosecutors invoke the law, defendants can no longer claim they acted in self-defense. Meanus had previous felonies related to drug charges and a robbery connected to a bar fight—so he was committing a felony by illegally possessing a gun. In the eyes of the law, the rest of what happened the day of Dunham’s death no longer mattered.

“They said I need to be locked up,” Meanus said, emotion heavy in his voice. “They said I was a danger to my community. They said I was trying to commit murder. And I was like, somebody please say something! It’s not true!”

So on July 28, 2022, Meanus took the 12-year sentence and entered an Alford plea, which allowed him to maintain his innocence on the record while acknowledging that the state would likely find him guilty if he went to trial. Absent further appeals or clemency from the governor, he will spend the next decade or more in a cell.

Meanus is not alone. There are at least 10 men in the state of Missouri who are serving sentences for felony murder in cases where they maintain that they killed someone in self-defense, according to a three-month investigation by The Appeal and the Yale Investigative Reporting Lab. The Appeal also spoke to 10 public defenders across the state. Eight said they either had such a case in their district or knew of one nearby.

Of the 10 men who say they shot someone to save their own lives, seven had prior felony convictions at the time of the shooting.

According to a study by the Sentencing Project, there were at least 67,800 felons on parole or probation in Missouri in 2020. The situation raises questions about who Missouri believes deserves the right to fight back if someone is trying to kill them.

“If you are a convicted felon in Missouri, you have lost your right to self-defense,” Hatley told The Appeal.

Ruth Petsch, the district defender in Kansas City—Missouri’s largest city—seethed as she spoke about the law’s impact in her district.

“Once you become a felon, you lose all these rights to keep a job. It’s harder to get housing. It’s harder to get assistance,” she said. “You’re left in a neighborhood where you’re more likely to have someone put a gun in your face like that. But in Missouri, once you become a felon, you just have to get shot.”

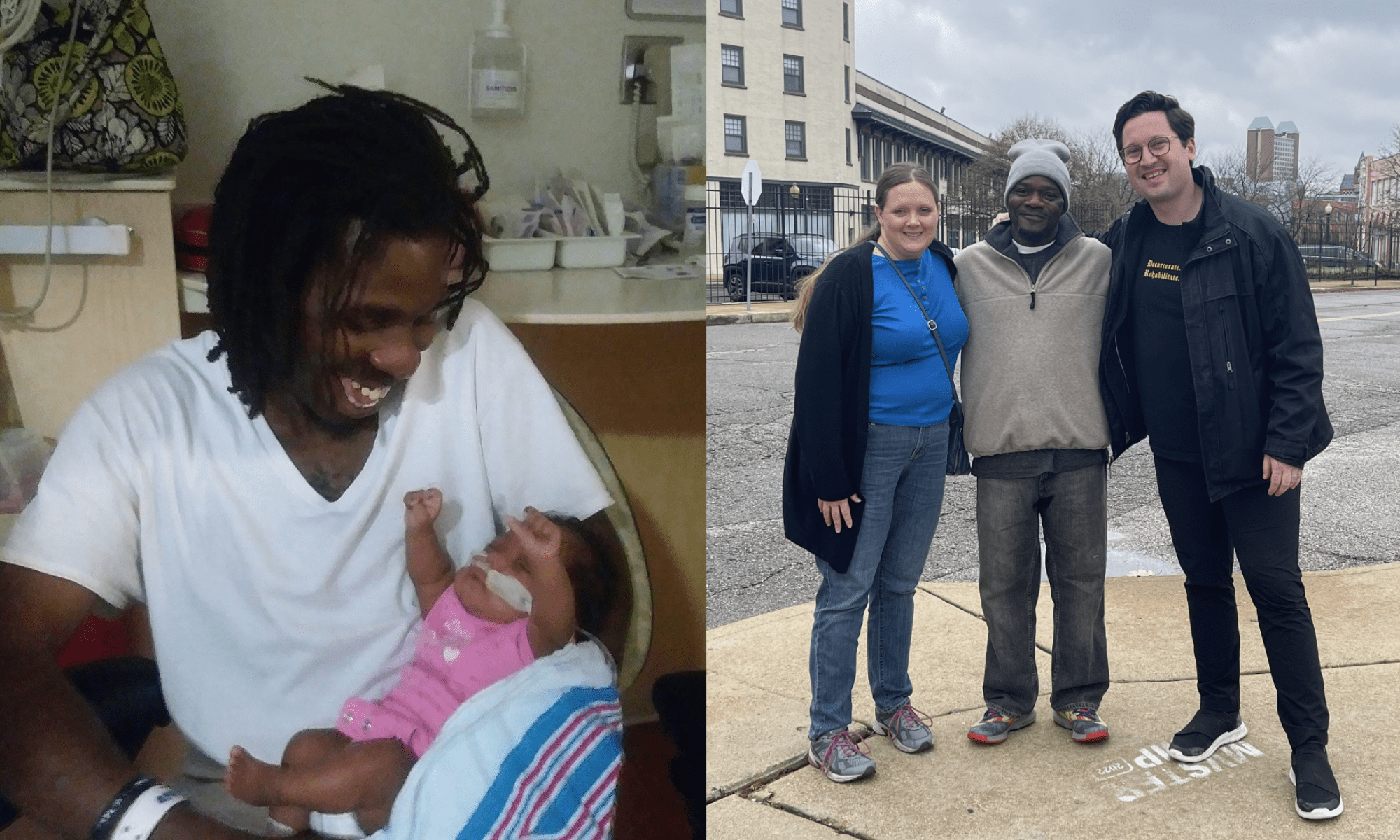

Josh Lohn, a public defender working in St. Louis, told The Appeal that he first became frustrated with the felony-murder law when he was assigned to defend a 49-year-old named Robert Smith who, like Meanus, had killed someone in a situation where he thought he was going to die.

Smith was making dinner in November 2019 when his elderly roommate—who, according to court records, was high on fentanyl and cocaine at the time—suddenly slashed at him with a knife. According to Smith, the pair fell to the ground grappling until Smith pulled out the gun he kept at his side and fatally shot his roommate. Smith had a prior felony conviction—a DUI from nearly two decades ago—and thus was in illegal possession of a firearm. Just like Meanus, Smith says he would likely be dead now if he hadn’t had the weapon.

But the prosecution found a way around Smith’s self-defense claim—by filing a felony-murder charge. The Missouri Supreme Court has at least three times issued rulings saying self-defense has no bearing in felony-murder cases, because, per the statute, all that must be proven is the underlying felony.

“[The prosecutor] admitted to the judge, on the record, that the reason he did that was because he knew that you could not use self-defense as a defense to felony murder,” Lohn said in an interview with The Appeal, during which he spoke for nearly an hour, interrupted only by his own increasingly agitated sighs. “It’s a disgusting misuse of the law.”

The prosecutor in Smith’s case, Srikant Chigurupati, did not respond to requests for comment.

Smith was convicted at trial and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Prior to sentencing, Jason Cummings, the jury foreman in the case, wrote Missouri 22nd Judicial Circuit Court Judge Katherine Fowler a letter asking her to give Smith the “most lenient sentence possible,” since it “was clear that Robert … was doing his best to make ends meet and stay out of trouble in a very violent and dangerous part of St. Louis.” Fowler later re-sentenced Smith to five years probation.

Cummings, a financial planner originally from Columbus, Ohio, told The Appeal that he’d never heard of the felony-murder statute before being asked to convict someone under it.

“I said to myself, ‘What the hell is that?’” Cummings said. “I remember thinking, ‘I don’t feel good about this.’”

In Missouri, this law is disproportionately applied against people of color. 82.6 percent of the population is white, and 11.8 percent is Black. But six of the 10 men identified in these felony-murder cases that involve a self-defense claim—and two of the three from Greene County—are Black. A majority (54.9 percent) of people convicted of felony murder in the state since 2010 have been Black, and only 34 percent have been white. Additionally, according to Missouri’s 2019–2020 Offender Profile, felony murder was the 14th most common charge brought against Black people. The charge didn’t even make the top 20 for white people.

More than one out of every six Black people convicted of felony murder were minors at the time of the crime, sometimes as young as 13. And 84 percent of all the minors convicted were Black.

Another Missouri man, Matthew Borg, was charged with felony murder in 2021 after an incident in which he says a man wielding a baseball bat broke into his hotel room and attacked him. Borg shot the man dead, but he was illegally in possession of the firearm he used, because of a past felony conviction. So, just like Meanus, he took an Alford plea and was sentenced in November to 12 years in prison.

Borg and Meanus are two of 16 people convicted of felony murder in Greene County since 2011.

“I just don’t understand,” Borg told The Appeal. “All of a sudden [Borg’s public defender] was telling me ‘You got to take this [plea]. We have no options whatsoever. This can’t go to trial.’”

In an interview, Greene County’s chief assistant prosecuting attorney, Joshua Harrel, firmly stood by his office’s use of felony-murder laws.

“This is one tool that the current state of Missouri law has given us that allows us to get some of those weapons off the street and those who would be using them illegally off the street,” Harrel told The Appeal.

Harrel said he believes that when a person is dead who would not be dead but for the actions of a defendant like Meanus, it is a prosecutor’s duty to file charges. He added that, in his opinion, people must be deterred from creating dangerous situations and said using felony murder is one way to accomplish this. But as the legal scholar Guyora Binder, author of the book “Felony Murder,” , writes, “undeserved punishment [under the felony murder rule] may … provoke more crime than it deters.”

Harrel was not the lead prosecutor on Meanus’s case. But he agreed that, if the case had not been a felony-murder case, his office would not have had enough evidence to refute Meanus’s self-defense claim.

“But I would not have hesitated to file felony-murder charges on Mr. Meanus’ case,” Harrel said. He scoffed at the public defenders’ assertions that self-defense ought to be taken into consideration and said there wasn’t a world in which he could imagine a jury having sympathy “for people engaged in these kinds of behaviors.”

The afternoon Meanus pulled the trigger to defend himself wasn’t the first time he had seen someone die. That was when he was four years old.

In 1995, in a cramped apartment on the Northside of St. Louis, his aunt cut his uncle’s throat as Meanus looked on. Meanus said he still has PTSD from that day and experiences violent dreams. Sometimes he’s chased by his aunt. Sometimes it’s by the bottle of beer she drank after she did it.

Troubles continued to follow Meanus throughout his youth. At a family gathering when he was eight, Meanus said, he was molested. When he was 17, Vashon High School expelled him for what he calls a misunderstanding involving an altercation with one of the school’s security guards. (The school did not respond to a request for comment.)

Afterward, he attended Sanford-Brown College’s medical assistant program for six months, but he says the school asked him to leave upon discovering he had not completed high school and didn’t have a GED. Not finishing school has always hurt. He remembers a day in elementary school when he overheard his teachers saying math was the hardest subject for kids to learn. That day, math became Meanus’s favorite subject.

By age 21, he found himself in perpetual turmoil, struggling with a meth addiction, and alternating between sleeping on the streets and staying on the couches of various cousins and aunts.

“I was really trying to stay in school, but I couldn’t get a break,” Meanus said. “I was hungry. Homeless. Just feeling like everything was unfair.”

Meanus left St. Louis that year to stay with his younger brother in Springfield, Missouri. Springfield, the state’s fastest-growing city, sits in Greene County—a red county in a red state. Much of the city’s Black population left during the Great Migration, largely prompted by a 1906 incident in which three Black men were lynched by a mob of more than 2,000. Sometimes called “The Buckle of the Bible Belt,” Springfield also hosts the headquarters of Bass Pro Shops.

In Springfield, Meanus committed the acts that made him a felon. The first: possession of a controlled substance—specifically, a few pills of Valium. The second came in May 2014, when he went on a pub crawl with some friends, and, in a state Meanus described as “high and not noticing everything,” got in a fight and ended up running off with the other man’s shoes. He was barefoot when police found him, and he told law enforcement that he thought the shoes were his.

He was never charged for the fight itself, but he later pleaded guilty to second-degree robbery for stealing the man’s footwear. He served six months in the Greene County Jail, during which he spent 84 days in a drug treatment facility. Meanus had no idea then that a drunken night, a pair of shoes, and three pills would eventually give the state the ability to lock him in a cage for more than a decade.

“I’m not a bad person,” Meanus said.

Around the time of his first felony charge, Meanus met and befriended Raquan White’s father, a preacher named Antoine White, who also ran a construction contracting business called We Do Floors, Paint and More. Soon after, Antoine offered Meanus a one-time job painting a house.

White told The Appeal that he noticed two things about Meanus during that first day of work: he didn’t “come up in a productive upbringing,” and he was a “positive-minded kid.” By the time Meanus was 26, not only had he landed a permanent position at White’s company as a home remodeler—a job he held until a few weeks before the shooting—but he had gotten sober, too. Along the way, Meanus started calling White “Pops” and began attending White’s church. At that job, Meanus also met the person who became his best friend: then-18-year-old Dalton Minnick.

“Antonio has always been someone that I can call and he would drop whatever he was doing to come help me,” Minnick, now 24, told The Appeal. “He would always call me randomly to make sure I wasn’t getting into any trouble.”

Minnick, whose round, boyish face stands out against the thick frame he has developed from years of labor, recalled a day when the two of them worked on a house until 11 p.m., only to get a call from Antoine asking if they could take care of another house. Minnick said Meanus looked at him for a moment, before saying, “Let’s go work these hours.” The job lasted until four in the morning, and Minnick said Meanus still pushed him to show up to work later that same morning.

Every day before work, Minnick said, Meanus drove to a nearby town to pick up Minnick, even though the job they were going to was often only a few minutes from Meanus’s place. After work, they bonded while playing Call of Duty and Rainbow Six Siege.

“He’s been one of those people who works for everything he has,” Minnick said. “He doesn’t like to take handouts or anything. He works for what he’s gotten.”

In 2020, when Meanus was 29, he temporarily moved back to the Northside of St. Louis to be with family. At the time, St. Louis was the murder capital of America—87 murders per 100,000 people annually, according to the St. Louis Police Department and the Missouri Highway Patrol. While living there, Meanus said, he heard bullets ricochet down neighboring streets almost daily. Without any protection, he said, he would have been too afraid to sleep. So, even though he knew it was illegal for felons to possess firearms, he went and bought a handgun—the same one he grabbed when Raquan White called asking for help.

Few rights are more thoroughly enshrined in Missouri law than the right to self-defense.

It’s one of many states with a castle doctrine, which allows for the use of force against trespassers and intruders on one’s property. And, as of 2016, it’s one of at least 28 states with a Stand Your Ground law, which eliminates the requirement to retreat from an attack before using defensive force. Nearly 49 percent of the state’s population owns a gun, compared with 32 percent of Americans.

In 2022, former Missouri state Sen. Eric Burlison, who then represented part of Greene County and now represents all of Greene County in the U.S. House of Representatives, proposed a bill that would have shifted the burden of proof for self-defense claims onto prosecutors, who would need to show “clear and convincing evidence” that an attack wasn’t self-defense in order to convict.

Yet historically this inalienable right has often failed to apply to those who are not white property owners.

In her book “Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair with Lethal Self-Defense,” Harvard lecturer Caroline Light describes how, after the Reconstruction era, court cases from several states supported white men’s right to use lethal force in self-defense while in those same states, laws prevented Black Americans from even owning weapons to defend themselves. The repercussions of this history can be seen in an Urban Institute report that examined FBI data on more than 2,600 homicide cases from 2005-2010 and found that in states with Stand Your Ground laws, nearly 45 percent of cases involving a white shooter and Black victim were considered self-defense, while the same was true of only 11 percent of cases involving a Black shooter and white victim.

This legacy now permeates Missouri, in part thanks to the state’s felony-murder laws, which have been controversial since their conception.

What happens when somebody else is in this same situation? Were we supposed to sit down and die?”

Antonio Meanus

According to Binder, the leading expert on felony murder, these statutes have existed in the United States since the 19th century. Missouri’s current statute says that a person commits felony murder if he or she “commits or attempts to commit any felony, and, in the perpetration or the attempted perpetration of such felony or in the flight from the perpetration or attempted perpetration of such felony, another person is killed as a result.”

In most states, prosecutors can charge a defendant with felony murder only in certain circumstances. In Virginia and Vermont, a felony-murder charge can only arise from a death tied to a kidnapping, sexual assault, rape, arson, robbery, or burglary. But Missouri is currently one of only four states—along with Delaware, Georgia, and Texas—where any felony can be used as the underlying charge for a felony-murder case. According to the Missouri State Judicial Records Committee, prosecutors in the state have obtained felony-murder convictions against 315 people since 2010.

These convicted individuals include people who had no intention of committing a killing, who did not directly kill anyone themselves, and who may not have even been at the scene when the death they were convicted for occurred. In 2014, for instance, Joshua Brown fled an attempted traffic stop while a passenger sat inside his car. The passenger then fled Brown’s vehicle and shot and killed a Cedar County Sheriff’s Office official at a different location—but Brown was charged with the murder.

Felony-murder laws are also often used to charge drug dealers, in a manner that many harm-reduction experts consider backward and dangerous. In 2021, Travis Jaegers allegedly sold a woman fentanyl in Jefferson City, Missouri. Later that night, the woman overdosed on the drug and died. Prosecutors charged Jaegers with felony murder for her death, listing his drug-sale charge as the underlying felony.

Most controversially, when police officers kill someone, felony murder laws allow prosecutors to charge other civilians with the killing. In 2018, police officers in Aurora, Missouri, pulled over Savannah Hill and Mason Farris to arrest Farris for a parole violation. Police say Farris made the car lurch backward while an officer was standing nearby. Another officer fired into the car, killing Hill. Prosecutors charged Farris with her murder, even though a police officer killed her. Farris later pleaded guilty to lesser charges and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

According to Hatley, I’Shon Dunham had invited Raquan White to his apartment complex as part of a premeditated plan to rob him. Dunham, who went by Shon with friends and family, was living in foster care at the time.

Springfield Police said in a press release shortly after the shooting that they were dispatched at 4:41 p.m. that day and arrived to find four people at the scene—Meanus, White, Dunham, and an unnamed 16-year-old. Both Dunham and the other teen had been shot. According to Meanus and Hatley, once Meanus shot Dunham, the 16-year-old pulled out a gun and began firing at the car while White attempted to back the car away from the scene. Meanus, in the midst of oncoming gunfire, said he fired two more shots, one of which struck the unnamed individual, who was subsequently transported to a hospital without life-threatening injuries.

Police say Dunham died on the scene. Meanus, police say, was arrested alongside the teenager—who was also charged with second-degree felony murder related to Dunham’s death. White, who did not respond to requests for comment, was not charged.

In the days after the killing, Dunham’s mother, Juanita, spoke with KOLR 10, Springfield’s CBS affiliate. She told the station that Dunham had been placed in foster care after experiencing “life challenges.” She said he was working toward getting his GED, was an intelligent kid, and cared deeply for his siblings.

“This was just unnecessary,” she said. “First of all, you [Meanus] are a 31-year-old man. Why, why in the world would you be involved with a 17-year-old in any type of way? So, for him to take my child’s life under the circumstances, that’s very upsetting and that’s very hurtful.”

A comment on Dunham’s entry in the National Gun Violence Memorial’s database reads, “This is my brother and I really misss [sic] him.” A GoFundMe started for Dunham’s funeral expenses still exists online—it closed after raising $205.

“He was a caring, loving, smiling individual,” the page states. “I am bringing this apon my self to start a go fund me so his mom nor siblings have to stress on trying to get the expenses at this moment.” [sic]

Meanus told The Appeal that he’s never forgotten the toll his decision took on others.

“When they told me he was 17, I broke down in tears,” Meanus said. “That’s not fair, man. That hurts me more than anything. So sometimes I sit in here and think, ‘Maybe I do deserve this punishment?’ because a young person lost his life. But they were in the wrong, and our lives were in immediate danger.”

The state set Meanus’s bond at $150,000, which he could not pay.

During preliminary court hearings, Meanus recalled, prosecutors tried to portray him as a menace to society. Meanus says the state submitted into evidence a music video he’d posted on Facebook, in which he held a gun and rapped. Harrel told The Appeal that prosecutors submitted the video to show the judge that Meanus was a dangerous person.

Meanus told Antoine White, Raquan’s father, about the video after the trial. Antoine told The Appeal that his stomach sank in a familiar way.

“I’m just going to be real with you, it’s because he’s young and Black,” Antoine said. “I’m not going to say it’s solely based on that, but that’s the narrative they like to draw.”

At least 31 percent of those convicted of felony murder in Greene County have been Black, though only 3.5 percent of the county’s population is Black. In Missouri’s bigger counties, this divide deepens. In Jackson County, which contains most of Kansas City, 72 percent of those convicted have been Black, and in St. Louis County, the total is 93 percent, despite both counties having populations that are roughly one-fourth Black.

In the City of St. Louis, 46 people have been convicted of felony murder since 2010. All 46 of them were Black. Black people make up only 45 percent of the city’s population.

Meanus said it seems to him that this system was never looking out for him in the first place.

“I never felt I was in the wrong,” Meanus said, trying and failing not to raise his voice. “I never left the scene, I called the police. I was in the right. But I had to take the plea because they’re using this law to get people to stay locked up. Knowing there are others like me, it makes me sick to my stomach. What happens when somebody else is in this same situation? Were we supposed to sit down and die?”

In January 2023, Meanus met with Hatley to go over their last shot. In a month, their chance would go away, for good. As Meanus’s big, brown eyes moved over the paperwork that would have to be filed, Hatley described the last option before them: filing for post-conviction relief, which could allow Meanus to present new evidence and reopen his case. After all, the plea Meanus took allowed him to maintain his innocence throughout the entire process.

But Hatley said he couldn’t advise Meanus to try to reopen the case. Doing so could backfire and Meanus could wind up sentenced to even more years in prison. Meanus’s case, Hatley said, continues to haunt him.

“I said to him, ‘I would love to be able to give you a different answer,’” Hatley told The Appeal. “‘You know, maybe the law will change someday, but that doesn’t help us today.’ I feel so sorry.”

Since the shooting, Antoine White has visited Meanus from time to time. He said he believes it’s important to show Meanus that there are people who will go through this with him.

But White also said that as he sits with Meanus, he’s often filled with inner turmoil, because it’s hard to know what to say to someone with no easy options ahead.

“I hate to put it like this, but a lot of the conversations we’ve had have had to be conversations of acceptance,” White said. “And that’s really hard. Because I know that the more he thinks that he doesn’t want to be there, the harder it will be for him to maintain his stability. But it’s also hard to get someone to accept something when they know they’ve gotten a raw deal.”

So, when the February appeal deadline came, Meanus decided he couldn’t bear the risk. He chose not to file. Now, other than asking Republican Gov. Mike Parson for clemency, Meanus doesn’t have many ways to try to change the next 11 years of his life.

In the meantime, others around Missouri are fighting to rewrite the state’s laws. This summer, Lohn, the public defender in Robert Smith’s case, collaborated with Mary Fox, the director of the Missouri State Public Defender System, to draft an amendment to the state’s felony-murder clause of its second-degree murder statute—a change the group began lobbying for last fall. The amendment deletes the phrase “any felony” and instead lists first-degree burglary, first-degree robbery, arson, kidnapping, assault, and sexual assault as the only charges that can trigger felony murder. In a memo supporting the amendment, Lohn wrote that the change is intended to “narrow the application of felony-murder to situations that would not shock the conscience.”

“The injustice of this is something that has stuck with me,” Lohn said, recalling how much work it took for him to get Smith half a decade of probation. “I’m terrified for the implications for my clients and others like them if this [law] is allowed to stay. And I think any legislator who thinks about a brother, a sister, a father, a mother who might have a history like [Smith’s], who are put in the same position, I can’t imagine that they would not want them to be able to defend themselves.”

Though the amendment does not do away with felony murder entirely, it would bring Missouri prosecutors’ ability to use the law much more in line with the rest of America. Much of Lohn’s amendment uses identical language to a felony-murder amendment passed in Illinois in 2021, which necessitates intent and also allows provisions for self-defense. An amendment passed in California in 2019 allowed everyone who had ever been convicted of felony murder in the state to petition to have their sentence waived. Hawaii, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, and South Carolina have done away with felony murder entirely.

But as reform efforts take shape, Meanus has spent the past year getting familiar with the cell that will, for the foreseeable future, be his long-term residence.

At times, Meanus said, he’s waited for a feeling of acceptance to come. Or a belief that everything happens for a reason. Before he got locked up, almost everyone described him as nothing but positive and loving. But as he’s waited, those thoughts have been drowned out by another feeling.

It’s rage. A rage at the knowledge that because he saved himself, he’s now doomed to a cell where it feels like nobody is coming to save him.

“I wonder,” Meanus asked. “What are these laws about?”