The Supreme Court’s War on Miranda Rights in America

For decades, the Court has been carving out generous exceptions and crafting new rules that limit the Miranda warning’s real-world impact.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

If you’ve ever seen a police procedural on TV, you are likely aware that officers are supposed to tell you about certain rights when you’re arrested. “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can be used against you in a court of law,” a common version begins. “You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided to you before questioning takes place.”

This disclaimer, known as the Miranda warning, is the product of a landmark 1966 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Miranda v. Arizona. It is meant to protect Americans from submitting to the police simply because they think, under the circumstances, that they have no other choice. If police don’t first recite it to people who are in custody, anything they say during subsequent interrogations cannot be used against them in court.

In theory, at least. In the five decades since creating this safeguard, the Court has been consistently chipping away at it, carving out generous exceptions and crafting new rules that limit its real-world impact. Together, these carve-outs preserve the Miranda warning in form, while ensuring that it does as little as possible to keep people—especially members of marginalized communities—safe from abuse by police.

Ernesto Miranda was born in 1941 in Mesa, Arizona, the fifth child of an immigrant house painter. He dropped out of school after the eighth grade, and between 1957 and 1961, he was in and out of prisons in Arizona, California, Texas, Tennessee, and Ohio. By March 1963, Miranda was living in Phoenix and working as a produce worker when police picked him up one morning on suspicion of kidnapping and rape.

After standing in a police lineup and enduring two hours of questioning, Miranda confessed. But at no point during this ordeal did the police tell him about his rights under the Fifth Amendment, which broadly protects people charged with a crime from being forced to incriminate themselves, or the Sixth Amendment, which entitles them to the assistance of a lawyer. (A separate Supreme Court decision issued the same month Miranda was arrested, Gideon v. Wainwright, requires the government to provide lawyers for criminal defendants who cannot afford one.)

At trial, Miranda was convicted and sentenced to between 20 and 30 years in prison. The Supreme Court, however, reversed his conviction. In his opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren detailed the long history of police using physical and psychological coercion to “persuade, trick, or cajole [a suspect] out of exercising his constitutional rights.” He quoted from police manuals that encouraged officers to deprive suspects of “every psychological advantage,” and to create an atmosphere that “suggests the invincibility of the forces of the law.” He noted that people were still sometimes physically tortured during interrogations, too.

Even if people are aware of their rights, Warren emphasized, the power imbalance between law enforcement and civilians prevents them from asserting those rights. Ernesto Miranda, as Warren put it, was an “indigent” Mexican American defendant “thrust into an unfamiliar atmosphere and run through menacing police interrogation procedures.” The defendant in a case decided along with Miranda’s was, Warren wrote, “an indigent Los Angeles Negro who had dropped out of school in the sixth grade.” Expecting these men to challenge armed authority figures would treat hundreds of years of racial discrimination and police abuse as if they did not exist. Against this backdrop, without adequate protections, “no statement obtained from the defendant can truly be the product of his free choice,” he concluded.

The Miranda decision changed American criminal procedure, but had little effect on Ernesto Miranda’s case: Prosecutors tried and convicted him on the same charges, this time without using his confession. Paroled in 1972, he was murdered in a bar fight four years later.

During the last few years of his life, Miranda capitalized on his niche fame by autographing cards printed with the warnings and selling them for $1.50 apiece. In 2016, the detective who questioned him back in 1963 told The Arizona Republic that if he had ever encountered Miranda on the street, he would have asked for one himself.

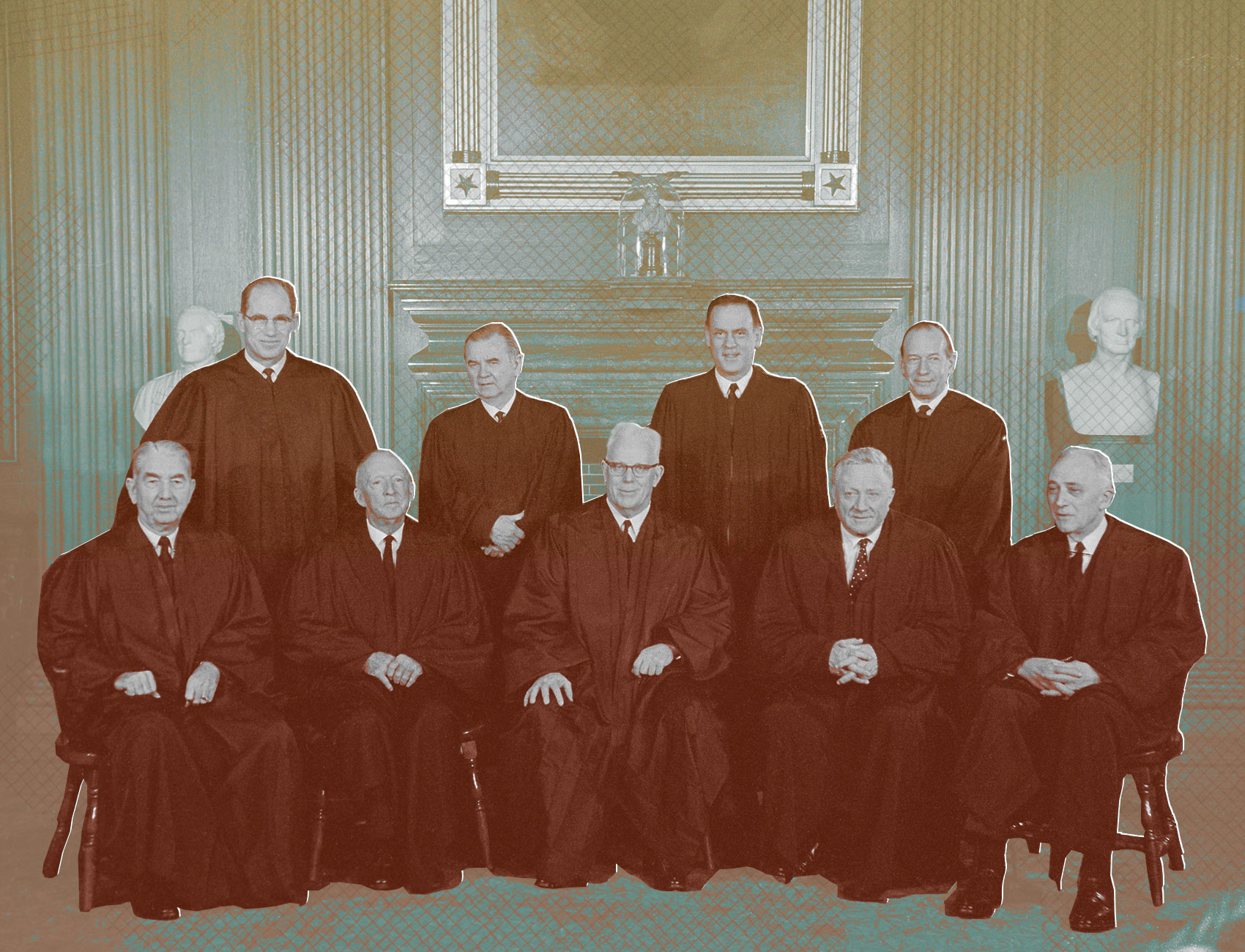

Miranda was one of several groundbreaking pro-defendant decisions handed down around this time by the Warren Court, which often championed the welfare of nonwhite and lower-income Americans whose well-being the legal system, to that point, had mostly ignored. The Civil Rights Movement had captured national attention at the time, and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative, which included the creation of sweeping anti-poverty programs like Medicaid and food stamps, was in full swing. That the Court agreed to hear Miranda’s case was no coincidence; in his book “Supreme Inequality,” journalist Adam Cohen notes that Warren specifically looked for cases that would allow the justices to craft a new standard for informing suspects of their constitutional rights.

The dissents in Miranda were vigorous and ominous, warning that the decision would embolden criminals, thwart diligent police work, and put dangerous people on the streets. “The Court is taking a real risk with society’s welfare in imposing its new regime on the country,” predicted Justice John Marshall Harlan II. “The social costs of crime are too great to call the new rules anything but a hazardous experimentation.”

A few years later, the newly elected President Richard Nixon set about the task of overhauling what was, to date, the most progressive Supreme Court in history. Within his first three years in office, Nixon managed to replace four of the Warren Court’s justices and installed a reliable conservative, Warren Burger, as chief. The Court has not had a true liberal majority since.

This increasingly reactionary Court quickly embraced the spirit of the Miranda dissents. In 1971, the Court said in Harris v. New York that prosecutors could use illegally obtained confessions to discredit a defendant’s testimony, even if they couldn’t use it as evidence of their guilt. For example, if a murder suspect said before receiving the warning that he pulled the trigger, and later blamed someone else, a prosecutor could tell the jury about a confession that Miranda would otherwise keep out of the courtroom. “The shield provided by Miranda cannot be perverted into a license to use perjury by way of a defense,” Burger wrote.

Creating this loophole, said Justice William Brennan in dissent, undid “much of the progress made in conforming police methods to the Constitution.” “It is monstrous that courts should aid or abet the law-breaking police officer,” he wrote.

Almost ten years later, the Court further weakened Miranda in Rhode Island v. Innis when it clarified what counts as an “interrogation.” After Providence police arrested Thomas Innis on suspicion of armed robbery, Innis said he wanted to talk to an attorney. As a trio of officers drove him to the station, two of them began talking—ostensibly just to one another—about the crime scene’s proximity to a school for students with disabilities, musing aloud about how terrible it would be if kids were to find the missing shotgun first. (“God forbid,” one said.) Innis, apparently overcome with anxiety, interrupted their conversation and led them to the gun.

In court, Innis argued that this charade violated his Miranda rights, since it took place despite his request for a lawyer. The justices agreed that “interrogation” includes actions that police “should know are reasonably likely” to elicit a response. Incredibly, however, they decided that Innis was not “interrogated,” even under this seemingly broad definition. Since the officers weren’t aware that Innis was “peculiarly susceptible” to concerns for the safety of disabled children, the Court said, they couldn’t have known their performance would prompt him to talk.

This is, as Justice Thurgood Marshall argued in dissent, ludicrous. Appeals to “decency and honor” are common interrogation techniques, and stage-whispering about small children dying by shotgun blast was more than “reasonably likely” to get Innis to talk—it was a dramatic ploy designed to accomplish that exact result. As Justice John Paul Stevens dryly noted in a separate dissent, the decision basically gives police a green light to ignore requests for lawyers, “so long as they are careful not to punctuate their statements with question marks.”

Perhaps the most absurd Miranda cases weaponize the warning’s first and most famous guarantee—the right to remain silent—against suspects who try to invoke it. In the 2010 case of Berghuis v. Thompkins, police presented Van Chester Thompkins, a suspect in a murder, with a written summary of his Miranda rights. Thompkins, perhaps wary of signing anything the police asked him to, refused to sign a form to acknowledge that he understood those rights, and offered only occasional, cursory responses during an agonizingly lengthy interrogation that followed. One of the officers who conducted the interview described it as “very, very one-sided,” and “nearly a monologue.”

Finally, after about two hours and 45 minutes of sporadic yeses, nos, and head nods, an officer asked Thompkins if he ever prayed to God for forgiveness for shooting the victim. Thompkins choked up, said “Yes,” and looked away. Based in part on his purported admission, he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

In Miranda, Chief Justice Warren had said that police must stop asking questions if a person indicates “in any manner” a desire to remain silent. In Thompkins, the Court flipped that principle on its head. Writing for the five conservatives, Justice Anthony Kennedy explained that silence, by itself, was not enough to invoke the right to remain silent; instead, suspects must assert it “unambiguously.” He also decided that here, police reasonably concluded that Thompkins’s one-word answer—after enduring nearly three hours of one-sided questioning—indicated a desire to waive his rights.

This logic ignores the realities of race, class, and power that were so important to Warren’s reasoning in Miranda. “Ample evidence has accrued that criminal suspects often use equivocal or colloquial language in attempting to invoke their right to silence,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent; they are in an unfamiliar environment, probably handcuffed, afraid of what might happen if they don’t cooperate. Even if police insist they aren’t technically under arrest, they may not feel they can actually leave, especially if they are Black or Latinx. And even if they know about the Fifth Amendment’s guarantees, they may not feel safe trying to bring them up, let alone in a manner police deem sufficiently clear. Thompkins uses justifiable feelings of powerlessness to render people, in fact, powerless.

The decision, Sotomayor warned, would encourage police to “question a suspect at length—notwithstanding his persistent refusal to answer questions—in the hope of eventually obtaining a single inculpatory response.” She also pointed out the cruel irony of this standard: To exercise the right to remain silent, the Supreme Court now requires you to speak.

In 2013, the Court extended the Thompkins logic even further, holding in Salinas v. Texas that if a person who isn’t in custody doesn’t answer a police officer’s questions, that silence can be used against him in court later unless he expressly invokes his Miranda rights—rights that police haven’t even read to him yet. As Justice Stephen Breyer put it in a frustrated dissent: “How can an individual who is not a lawyer know that these particular words are legally magic?”

In response, Justice Samuel Alito argued in his majority opinion that treating silence as an exercise of the right to silence would “needlessly burden the Government’s interests in obtaining testimony and prosecuting criminal activity.” But by instituting a police-friendly rule instead, the Court made a deliberate choice to privilege the interests of police over the interests of people under their control. When Justice Harlan warned 47 years earlier that Miranda would endanger “society’s” welfare, his definition of society plainly did not include the untold number of people who would end up in jail because they were duped by police.

Underlying each of these cases is a consistent theme: the justices’ faith in police to scrupulously follow rules and refrain from abusing their power. There is little evidence that this trust is well-placed.

In the 1984 New York v. Quarles decision, for example, police found a handcuffed suspect’s empty holster and asked him where the gun was. Although officers hadn’t read Quarles his rights, the Court decided that the gun and his statements about it could be used at trial. Under the circumstances—as in Innis, a missing gun waiting to fall into the wrong hands—the Court explained that complying with Miranda would put police in the “untenable position” of choosing between protecting and serving on the one hand, and safeguarding civil rights on the other.

For police, this creates an obvious perverse incentive: to ask questions before giving Miranda warnings in the name of “public safety.” It allows them to cut constitutional corners based on the supposed exigencies of the moment.

The Quarles majority acknowledged this concern, but just as quickly waved it away, asserting that, more or less, everything will naturally work itself out. “We think police officers can and will distinguish almost instinctively between questions necessary to secure their own safety or the safety of the public and questions designed solely to elicit testimonial evidence,” wrote Justice William Rehnquist. This is an astoundingly credulous assessment of the restraint of the police, an institution whose willingness to resort to trickery, deception, and occasionally literal torture made the Miranda warnings necessary in the first place.

In a sometimes-blistering dissent, Justice Marshall excoriated the Quarles majority for subjecting the rule against coerced confessions to a crude cost-benefit analysis. “The majority should not be permitted to elude the [Fifth] Amendment’s absolute prohibition simply by calculating special costs that arise when the public’s safety is at issue,” he wrote.

Not every instance of official deception survives judicial review. In 2004, the Court struck down an especially brazen procedure in which police would first ask questions, then give Miranda warnings, and finally ask suspects to repeat the answers they had just given—this time for the record. Writing for a four-justice plurality, Justice David Souter referred to this strategy as one “adapted to undermine” Miranda, and argued that no reasonable person would have understood they had a choice about whether to talk.

But the impact of the Court’s war on Miranda is on the millions of unseen interactions that take place in interrogation rooms and squad cars—cases that will never make it to a courtroom, where a judge can belatedly rescue a wronged person from the state’s abuse. By putting itself in the shoes of police instead of the people harmed by police misconduct, the Court tips the balance of power in the direction of law enforcement, punishing people for not knowing what to say once the cuffs are on, unmoved by the consequences of reflexively giving cops the benefit of the doubt. Letting police push the envelope basically ensures that they will sometimes push too far, and get away with it without anyone ever finding out.

Today’s Court looks nothing like the one that decided Miranda: It is dominated by doctrinaire conservatives whose movement’s fondness for law-and-order politics cannot be disentangled from their jurisprudence. Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, is notorious for his indifference to the plight of poor, incarcerated, or otherwise vulnerable people. In 1992, he opined that Louisiana prison guards’ brutal beating of a prisoner was not cruel and unusual punishment because the injuries the man suffered weren’t “serious” enough. In a 1985 job application, Alito boasted that his interest in law stemmed from, in part, his “disagreement with Warren Court decisions, particularly in the areas of criminal procedure,” among others. Now, as a justice, he has the power to help peel back those decisions himself.

The justices’ collective work experience also informs this Court’s anti-defendant bent. Perhaps the surest career path to becoming a judge, other than being an officer in an Ivy League law school’s Federalist Society chapter, is to work as a prosecutor first. This is not a partisan phenomenon: Alito was the U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey, while Sotomayor spent several years as an assistant district attorney in New York City. According to a 2019 study conducted by the libertarian Cato Institute, 38.1 percent of surveyed federal judges came to the job with prosecutorial experience. In lower federal courts, former prosecutors outnumber former defense lawyers by a ratio of 4 to 1.

Not all prosecutors are the same, of course; in her opinions, Sotomayor has consistently demonstrated far more empathy for defendants than Alito and his fellow conservatives. But when ex-prosecutors are so well-represented among the ranks of judges, it means that a disproportionate number of people making decisions about defendants’ rights do so from the perspective of someone for whom successful assertions of those rights were once professionally inconvenient.

By contrast, no sitting justice has meaningful criminal defense experience; Marshall, the last one who did, stepped down in 1991. “You’d be hard-pressed to assemble nine lawyers in America who as a collective are further removed from the realities of the facts of these cases than the nine justices of the Supreme Court,” the Washington Post’s Radley Balko wrote in 2015, in an assessment unaffected by the Court’s recent turnover. Attempts to address this deficiency can make for easy fodder for law-and-order Republicans looking to scuttle a nomination. When federal appeals court judge Jane Kelly appeared on President Obama’s Supreme Court shortlist in 2016, a right-wing activist group quickly spent a quarter-million dollars on ads smearing her for her prior work as a public defender. In the United States, only one side of the criminal legal system gets treated as working in the public interest.

The purpose of Miranda was, as Chief Justice Warren wrote, to protect “human dignity,” ensuring that the existence of fundamental rights did not depend on the legal acumen of the person exercising them. But the Supreme Court has spent decades systematically hollowing out the decision’s promise, even as the federal judiciary’s rightward shift made the legal system less hospitable for criminal defendants. Today, only people who know their Miranda rights—and exactly what to say and do to invoke them—can hope to enjoy the protections they provide. Everyone else is on their own.

Jay Willis is a senior contributor at The Appeal.