If Mental Health Responders–Not Police–Had Come to Marquis Rivera’s Home, Would He Be Alive Today?

A mother and father – a mental health crisis worker himself – grieve the needless death of their son

This story was produced by MindSite News, an independent, nonprofit journalism site focused on mental health. Get a roundup of mental health news in your in-box by signing up for the MindSite News Daily newsletter here.

This story is the latest installment of Fateful Encounters, an ongoing investigative collaboration between MindSite News, the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago at Northwestern University and other media outlets exploring police response to mental health crises. This work is generously supported by the Sozosei Foundation.

Marquis Rivera was going to kill himself.

He said so to the 911 dispatcher right before he hung up. And he was a picture of distress when Officers George Chiang and Andrew Gilstrap arrived at his apartment complex in Columbia, Missouri, with their body cameras rolling.

During that first encounter on Aug. 4, 2023, Rivera, sitting shirtless on his front porch, shakes his leg and hands, says little and seems to say “mm-hmm” when asked if he’s planning to hurt himself. At one point, he says, “Just let me do what I gotta do.” At another point, Officer Chiang goes back to his car, calls Rivera’s ex-girlfriend and learns that Rivera owns a gun.

Back on the porch, Officer Chiang asks several times if Rivera wants to go to the hospital or talk to a psychiatrist. Rivera shakes his head, and later says he won’t talk to them. Chiang says he might compel him to go – but in the end he does not. Rivera tells the officers he’s going to go back inside to play video games, and they walk away.

Six minutes later, Rivera, a 22-year-old Black man, calls 911 again.

“Please just ask those police to get back over here,” he tells the same dispatcher.

When Chiang and Gilstrap pull up to the complex for the second time, Rivera’s crisis has escalated. And this time, he’s holding his gun. For the next several minutes, additional police cars roll up, sirens blaring. At least eight officers are now on the scene, many of them with their guns drawn.

The standoff continues for around 20 minutes, and then becomes fatal. In a situation commonly referred to as “suicide by cop,” a distressed Rivera raises his gun, and officers shoot and kill him in front of his apartment.

The encounter didn’t have to end that way, his loved ones say. In the time leading up to that fateful moment, there were several opportunities for police to get Rivera help.

“So many gray areas, red flags,” said Rivera’s stepfather, Ralph Edwards, in an emotional interview nearly a year after his son was killed. “If they would have had any kind of sense, (if) they would have had the right training in their own mind to be able to help my son and get him out of the situation that he (was) in, he would be alive today. But that didn’t happen.”

Edwards, who entered Rivera’s life when he was just 2 years old and helped raise him, is still haunted by one major question, the same one that hangs over so many other cases of people killed by police officers in the midst of a mental crisis: “Why didn’t you come with the appropriate people to handle the situation?”

Incredibly, Edwards himself is one of those people. For nearly two years, he’s worked in exactly the kind of role that might have helped his stepson last August, as a trained member of a mobile crisis response team that responds to hotline calls about mental health emergencies in the suburbs of Chicago.

If a team like his existed in Columbia, and had responded to Rivera’s calls, Edwards told MindSite News, his son would be alive today. But, like many American towns and cities, Columbia has no mobile crisis team.

His partner, Rivera’s mother, agrees. “When people are having a mental health crisis, it should be handled different,” Katuiscia Penette said. “Those people shouldn’t be handled like criminals. They just need help.”

A city’s unfulfilled plans

The desperate calls that Marquis Rivera placed to 911 that day are common occurrences in Columbia, as in most of the country. In 2021 and 2022, the most recent years for which data is available, the city’s police department received 3,352 mental health-related 911 calls, and almost half of them involved people who were potentially suicidal. That’s an average of 4.6 calls per day.

Some Columbia police officers have received Crisis Intervention Training, which teaches them how to de-escalate mental health crises, though the department declined to say how many officers have been trained. Whatever the number, these officers aren’t dispatched very often. Of the 3,352 mental health-related calls logged by the CPD in 2021 and 2022, CIT-trained officers were deployed just 610 times – about 18% of the time, according to data from the police department and Boone County.

Records show that the city made plans in 2021 to establish a co-responder program that would dispatch mental health crisis workers alongside police officers to jointly address mental health crisis calls. The city even posted a job for a social work supervisor to lead the collaboration and allocated $1.9 million over three years to bring the program to fruition. The money was never spent and the position was never filled.

In 2023, Columbia put out a request for proposals seeking outside contractors to operate the co-responder service and received an application from Burrell Behavioral Health, an agency that operates in 18 Missouri counties and, since mid-2022, has been running a co-response program in Springfield, Missouri, 160 miles southwest of Columbia. But in March, Police Chief Jill Schlude told council members that the department needed “to press the pause button,” and a Burrell spokesperson said in an email that discussions with the city were on hold. The department declined requests for comment.

First contact

Marquis Rivera called 911 for the first time at 3:05 p.m. that summer afternoon, and the police arrived 21 minutes later. He sat alone on his porch, staring straight ahead as Chiang and Gilstrap approached.

“What’s going on, man?” Chiang said in body camera footage of the encounter. Rivera shook his head. “You got a lot going on?” He nodded.

That’s how their dialogue continued for almost five minutes: Chiang asking questions, Rivera hardly speaking. Gilstrap stood to the side, silent the entire time. “I’m not no, like, mental health expert or anything,” Chiang said at one point. “I can give you advice, but I’m not a doctor.”

Eventually, Chiang asked Rivera if there was anyone he could call. He went back to his police car and dialed a number. It was Rivera’s ex-girlfriend.

Over the phone, she told Chiang about their recent breakup and how Rivera was struggling to let her go. She also said Rivera had a gun in his apartment, which was usually either in his room or on him. “Huh, that’s interesting,” Chiang responded. The topic of the gun never came up again.

Outside, it was silent. For the 14 minutes Chiang was away on the phone with Rivera’s ex, Gilstrap stood off to the side, facing Rivera without speaking. He shuffled around. He checked his nails. His body camera footage showed Rivera using his phone, then staring straight ahead, then tapping his foot anxiously and putting his head in his hands.

Back in his cruiser, Chiang told Rivera’s ex he might invoke Missouri’s involuntary commitment statute and forcibly transport him to a hospital for a mental evaluation. “I think with what you’ve told me, like, I have enough to forcefully commit him here,” Chiang says.

Chiang exited his car and returned to Rivera. “I think you should go to the hospital and talk to someone about this, man,” he said. Rivera shook his head. “You having thoughts of harming yourself?” Chiang asked. “Mm-hmm,” Rivera replies.

Still, Chiang took no action, made no effort to detain Rivera. Instead, he repeated the same question that Rivera had already answered – whether he was thinking about hurting himself.

Rivera wasn’t responding anymore. He just stared straight ahead as Chiang spoke, shrugging or not reacting. “I just need a yes or no,” Chiang said at one point. “C’mon dog, work with me a little bit.”

And that’s how the exchange ended. The closest Chiang got to initiating an involuntary detention was when he said, “It’s not gonna be a choice, we’re gonna have to go.” But by then, Rivera seemed fed up. He told Chiang he was good, that he no longer needed help. He was going inside to play video games.

Chiang and Gilstrap left.

Rivera’s entire family watched this all play out in the officer’s body camera footage. “They left him after he said that he wanted to hurt himself,” his mother said later. “They knew he had a gun, and they told the ex-girlfriend they would get him some help. They just didn’t.”

Since the Columbia Police Department never followed through on its plans to create a mobile crisis team with mental health professionals, uniformed police officers were the only options available when Rivera called back a few minutes later. This time, he had his gun.

What happened next was described by Chiang in an interview with a Missouri State Highway Patrol investigator. As the officers stepped out of their vehicles for the second time that afternoon, Rivera fired the gun in the air four or five times. Rivera then threw the gun on the ground and put his hands up, telling police to shoot him. With their guns drawn, Chiang and Gilstrap called for backup and shouted out orders. Rivera walked over to retrieve the gun – which Chiang believed was then empty – and told police he was going inside his apartment to reload.

When he returned outside, more officers had arrived. They spread out around him, guns drawn. Dashcam footage shows that after a few minutes, Rivera raised his gun toward the police.

At least four officers fired, according to Highway Patrol investigators, and Rivera went down. One bullet went through his left knee and another straight through his chest. Rivera’s mother hasn’t watched this moment in the footage, though the rest of her family has. She just isn’t ready to watch her baby die.

A hyper boy who loved to crack jokes

Penette, a mother of four, gave birth to Rivera at age 24 in Evanston, Illinois. He was her second eldest, the hyper one. The one who cracked nonstop jokes and always talked with his hands. The one who started breakdancing in the middle of the street to make his friends laugh. The only time Rivera sat down to relax, she recalls, was when he went to bed at night.

He also loved hard, and cared deeply about the people close to him. His younger sister, Katiana Edwards, described him as fiercely loyal, someone who would give her the shirt off his back – and catch cicadas in the summertime just to chase her down the street with them.

But his hyper energy came with a temper. If Rivera didn’t agree with the rules, he refused to comply. And with his parents running a tight ship at home, he rebelled constantly.

During his senior year of high school, something changed. He and his friends – a trio of boys who bonded over music, skating and deep conversations – began smoking weed. Rivera’s grades plunged to the point where he barely graduated, and he lost interest in the activities he once excelled in, like running track.

His home life took a downturn, too. As Rivera grew more rebellious, family relationships unraveled. Arguments broke out between Penette and Rivera about missed curfews and broken rules – a relentless battle between a strict household and a longing for freedom.

Halfway through his senior year, Rivera lashed out at his parents and siblings in a family-wide fight. Penette’s mother – Rivera’s grandma – offered to take him in for a while at her home in Rogers Park.

But Rivera still struggled. Not only did the daily, crosstown commute to school take a toll on his attendance, but he also showed signs of declining mental health. “I knew he would be feeling a type of way sometimes,” his sister remembered. He listened to sad music constantly, and he seemed to plaster on a smile.

Rivera managed to graduate and moved into a nearby apartment with his older brother. During that period, the four siblings would often hang out together for hours, with the occasional movie-marathon sleepover, Edwards recalled.

But at 21, Rivera began yearning for something new, a place where he could thrive on his own. Along for the ride was his best friend, Jared McCrary, who had just graduated high school. They settled on Columbia, Missouri. “It’s cheaper to live there, and I can find my own way,” Rivera’s mother remembers him saying. She was hesitant. She hadn’t even known that city existed.

But the circumstances were right. A friend had lined up jobs for Rivera and McCrary at a cannabis farm in Columbia, and the pair had found an apartment with two rooms available. Halfway through 2022, they moved to the new city, around 400 miles from Evanston.

Things went well for a while. They enjoyed their jobs and their independence. Rivera met a girl, and they fell in love. But adjusting to his new life became difficult. Rivera struggled to wake up for work and eventually lost his job at the farm because of it. After a brief stint at Dunkin’ – where he told McCrary he wasn’t treated well – Rivera was left unemployed.

The job search was challenging, and Rivera leaned on his girlfriend throughout it. “She kept him sane,” McCrary remembered.

Rivera also turned to video games, livestreaming frequently on Twitch. He gathered a following through his constant streams, sometimes playing for 24 hours straight. His passion for streaming motivated him, but it also exhausted him. McCrary remembers coming home several times to Rivera sleeping in the middle of the afternoon, and he would stay that way until morning.

That’s when his relationship, then nine months long, began to sour. In late July 2023, Rivera’s girlfriend broke up with him. “It really messed him up,” McCrary said.

On Aug. 3, McCrary came home from work and checked on Rivera. They talked for a while in Rivera’s room, and McCrary played him a song he’d recorded. Everything felt normal.

At 6:15 p.m. the next day, McCrary came home from work to police cars and yellow tape wrapped around his apartment.

McCrary’s last memory of the man he called his brother – the man who taught him to value loyalty over money, to respect people for who they were and to “appreciate the beauty of life” – was his corpse under a tarp in front of the apartment they had shared.

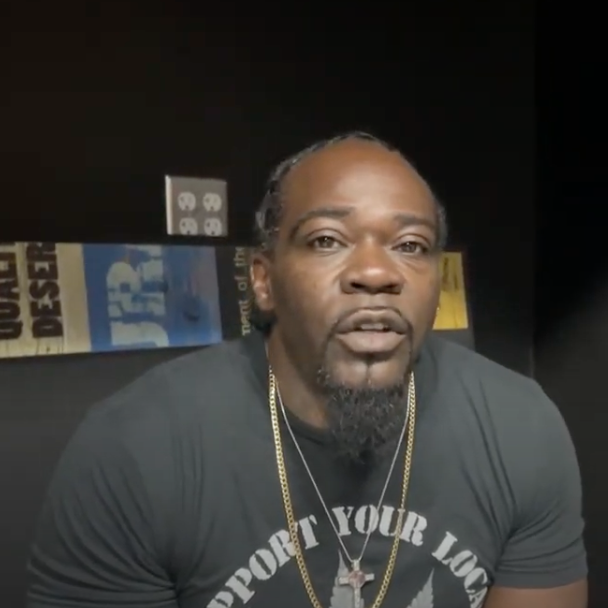

Being a mental health specialist and a father watching this, I want justice.

Ralph Edwards

Ralph Edwards, Rivera’s stepfather, helped raise Rivera, entering his life when he was 2 years old. His experiences – as a father, husband, reformed gang member, anti-violence advocate, recovery counselor and, most recently, mobile crisis responder – give him a unique insight into what happened to his son.

“My son calls the police and ends up being killed by the people that he wanted to help him,” Edwards told MindSite News. “Being a mental health specialist and a father watching this, I want justice.”

Edwards didn’t know of his son’s hardships in Columbia until it was too late. When Rivera called home with life updates from Columbia, he would speak of his girlfriend and his passion for gaming. Looking back at that fateful day, Edwards wishes that he could’ve been there to talk Rivera through it.

One thing he feels certain of: the officers mishandled the interaction.

First, he says, they failed to engage Rivera in conversation. Officer Gilstrap stayed silent the entire time, even when he was left alone with an anxious Rivera for 14 minutes. Officer Chiang failed to invoke an involuntary detention after saying he would. And perhaps most significantly, Chiang knew Rivera had a gun but did nothing about it, then repeated the same questions about Rivera’s mental state until Rivera said he was “good.”

Jillian Snider, a retired New York police officer who now directs criminal justice and civil liberties policy at the R Street Institute – a free market-oriented think tank – has a somewhat different view. From a police protocol standpoint, she said the officers “put forth a pretty valiant effort in keeping the situation as calm and composed as humanly possible.”

After watching the body camera footage of the first encounter, her only issue with Chiang’s actions was that he failed to follow up after learning that Rivera had a firearm.

During her 15 years on the force, Snider said she never underwent CIT training. This training is vital when police respond to mental health crises, says Amy Watson, a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who studies crisis services. But even CIT-trained police are not the best options for handling such emergencies. “If someone’s calling 911 with a suicidal crisis, ideally, there would be some ability to access a mobile crisis team that has more capacity to address the situation,” she said.

Columbia didn’t have the option to dispatch a mobile crisis team because the city never took the steps to create one. Still, Edwards says, the officers could have approached the second encounter in a less confrontational manner and subdued Rivera without resorting to lethal force when he threw his gun to the side or walked back to his apartment to reload.

“You fumbled the ball the first time and didn’t get it right. Now you have the second time, a second chance to get it right and really help this individual,” Edwards said. “If you would’ve done what you were supposed to do, my son would be alive.”

A dire shortage of clinicians

Columbia, a city of 120,000 people, sits in the heart of Missouri’s Boone County. Home to the University of Missouri, the city attracts thousands of people every year, who flock to Columbia for college and its beloved sports teams. For Rivera and McCrary, the city’s cheap living costs and job availability were its main selling points.

But the city – and the state – has serious drawbacks for people who struggle with their mental health. According to the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, Boone County is a designated shortage area for mental health professionals, as are 112 of the state’s 115 other counties.

Mental health professional organizations have worked for years to overcome these deficits. The Missouri Behavioral Health Council has tried to increase awareness of 988 – the national suicide and crisis hotline – and establish more behavioral health clinics across the state.

Local advocacy groups also attempt to compensate for the deficiencies. Columbia’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness holds two support groups: one for family members of individuals with mental health conditions and another for mental health recovery support.

Heather Harlan, a volunteer at NAMI Columbia, said stigma surrounding mental health is gradually fading. Her son, who lived with deep depression and bipolar disorder, died by suicide at age 36. “People are becoming more aware that mental health is part of our healthcare and much more frail than we all realized,” she said.

But the shortcomings are still apparent. Though 988 has emerged as a national crisis hotline, many people still default to dialing 911 for mental health emergencies, as Rivera did.

“Perhaps if Marquis had known about 988, to call that number instead of 911,” Harlan said, things could have been different. Wayne State’s Watson said a 988 call-taker would have taken an alternative approach to Rivera’s call – focusing on his mental state from the start – though it’s difficult to say whether Rivera would have engaged in further conversation.

Much still needs to be done, Watson says, to increase awareness of 988 as an option and to ensure that civilian crisis response teams are available in all cities. The alternative – response by law enforcement – has contributed to the deaths of 1,958 people experiencing a mental health crisis since 2015, according to the Washington Post. MindSite News and Medill have been documenting the harms of police response to these crises in our Fateful Encounters series.

Police departments across the country have adopted Crisis Intervention Team training, a 40-hour program that offers a series of courses on suicide intervention, behavioral health disorders, de-escalation strategies and more.

The state of Missouri has worked toward integrating CIT training with the establishment of the Missouri CIT Council. According to public records obtained by MindSite News, the Missouri CIT Council has certified over 11,000 law enforcement officers with 415 training sessions across the state. But of these, only six CIT training sessions have been held in Mid-Missouri – a region covering six central Missouri police departments, including Columbia.

In the past, the CPD told Janet Thompson, the Boone County District II Commissioner, that 100% of its staff were CIT-trained, she said. But when she called 911 one Saturday morning in 2023 to request that a CIT-trained officer perform a wellness check on a former colleague, no such officer was on call. “They said the next time a CIT-trained officer would be in was the next Monday,” Thompson said. “That’s two full days without a CIT officer.”

The CPD declined to say whether the officers involved in Rivera’s death had completed CIT training.

On call

Ralph Edwards started working as a mobile crisis responder in the Chicago area nine months before his stepson was killed 400 miles away.

“If it was me, I would have definitely assessed the situation, saw the body language, saw the sweating and muscle spasms of the individual sitting in front of me, and just told myself that this is not right,” Edwards said. He said if he were in Chiang’s shoes, as a responder without mental health expertise, “I would call somebody that probably does have the training because I want to get this person some help.”

But non-police responders trained specifically to handle mental health emergencies don’t exist in Columbia. They do in Springfield, Missouri, however. Burrell Behavioral Health, the agency that bid on the never-created co-response program in Columbia, has put five mental health professionals in the field with Springfield police, helping address gaps in the way the city responds to emergencies.

“Our police officers are very well-trained, but they don’t have the time to build rapport to find out what the person needs,” said Holli Triboulet, Burrell’s project director in Springfield, who also works as a co-responder. “Our co-responders are able to quickly identify those things and assist them accordingly.”

Those co-responders handled 751 calls for service in 2023 despite staffing shortages and limited hours. Those hours will soon increase, Triboulet said.

With an initial grant from the Missouri Foundation for Health set to expire in January, Springfield has secured an $800,000 grant from the Missouri Department of Public Safety that will double the team and ensure full 24/7 coverage for two years.

Back in Columbia, progress remains stalled. Had the city’s program been implemented back in 2021, when the idea emerged, Rivera’s story might have ended differently, said his stepfather. “It hurts,” he said, “but it strengthens my fight for my son.”

On the weekends, Edwards leaves his work phone on all day. He never wants to miss the next mental health emergency call, whenever it might come.

‘Race matters, friends’

Traci Wilson-Kleekamp, a Columbia resident and community activist, has lost trust in her city’s commitment to operate a co-response program.

“They don’t want it to work,” she said. “They don’t want to have co-responders because they think those people will get in their way. The police are still stuck in a warrior mentality, and getting them to think more deeply about interrupting violence and having a different kind of response to mental health is challenging.”

In her work for local nonprofit “Race Matters, Friends,” Wilson-Kleekamp, who is Black, said she’s observed years of ineffectual and racist police intervention in the city. In July 2023, she and her son observed an altercation in downtown Columbia: A Black man in the street, just off the sidewalk, was desperately yelling for help. Surrounding him were at least five police officers – two of whom were crouching next to him and restraining his arms behind his back.

Her son wanted to be a witness, so they pulled over. They approached the scene and took videos of the man in a panic, breathing heavily and squirming in the two officers’ grip while others stood close by and watched. As Wilson-Kleekamp’s son approached, the man screamed, “Help, they gon’ try to kill me… They gon’ kill you too.”

“This is a normal encounter in Columbia,” Wilson-Kleekamp said later. “To me, that is very problematic, because I understand if I’m dealing with a person that’s in distress, just standing around watching while crowding them in makes it worse.”

Wilson-Kleekamp said faulty police responses to mental health crises intersect with patterns of anti-Black racism in Columbia. The city has a long history of racial tensions, with multiple periods of community-wide protest. In 2015, student protests broke out at the University of Missouri over how the administration responded to racist incidents on campus, leading to the then-president’s resignation. More protests followed George Floyd’s killing in 2020.

A national analysis of public records by MindSite News shows a strong racial disparity in police response: In city after city, police are most likely to use force or weapons such as Tasers when responding to Black people in mental health crisis – especially men.

While Black residents say this pattern holds true in Columbia, the police department has declined to provide data from its use-of-force incident logs, so MindSite News has been unable to conduct an analysis.

A mother’s grief

When Katuiscia Penette talks about the pain of losing her son, her eyes turn a glassy red, and she looks anywhere but forward. Her voice, usually spirited and powerful, grows hoarse and trembles.

“I know it took him a lot to even reach out for help in the first place,” she said. “I wish that he had reached out to my family or he had reached out to me.”

Penette’s pain doesn’t just stem from that fateful day last August. It also comes from everything that occurred after.

On the Friday Rivera was killed, the police never notified his family. His loved ones found out from McCrary, who called them when he arrived home, hours after Rivera died.

Penette’s first instinct was to get to her son as soon as possible. But she was in the Chicago suburbs, and he was 400 miles away. The family called the coroner, asking if they could see Rivera. The coroner told them his body had already been transported to the city morgue, which wouldn’t be open until Monday. There was no point in making the drive now, the coroner said, especially with a rainstorm going on.

So they waited. The next two days were utter agony. Late Sunday night, the family piled into two cars and drove to Columbia. They wanted to be there right when the morgue opened in the morning. But when they arrived, they were told the morgue wasn’t open to the public, and there was no way to see him unless a funeral home came to pick up his corpse.

It wasn’t until Thursday, six days after he was killed, that his family got to see his body.

They were furious. They had watched the body camera footage of the first encounter and the dashcam footage of the second, which was only released to them after they wrote a letter to Columbia’s mayor. What they saw in the footage appeared to them as obvious negligence and unnecessary use of lethal force.

In the following months, the Missouri State Highway Patrol launched an investigation into the shooting, which closed in October 2023. After reviewing the investigation reports, Benjamin Miller, the attorney assigned as special prosecutor for the case, announced in February that he wouldn’t be pressing charges against the officers. Rivera had posed an imminent threat to public safety when he raised his gun, Miller said. The officers had reacted appropriately.

The news prompted outrage among Rivera’s loved ones. The officers should be held accountable for their negligence, they said. In February, Rivera’s sister took to TikTok to share his story, amassing 1.7 million views on one video.

Since learning of Miller’s decision, they’ve been searching for an attorney to sue Columbia for negligence. So far, they’ve raised about $7,000 on GoFundMe for it.

Though the police department issued a press release on Feb. 9 extending its condolences, Rivera’s family said no one from the department has ever called them – to apologize, to offer support or even just to acknowledge his death.

“I just have a void in my heart,” his mother said. “The world just failed him. That’s a mother’s worst nightmare.”