Mental Health Crises Require Mental Health, Not Policing, Responses

At least a quarter of all people killed by police each year suffer from untreated mental illnesss. New York City’s Public Advocate is proposing a new hotline and mental health crisis teams.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

For several years now, it has been apparent that police are not and cannot be the appropriate response to mental health crises. The reasons are clear: Police officers have little to no expertise in handling people in psychiatric distress. They often approach people with a fear that is unwarranted and rooted in that lack of expertise and experience. That fear and lack of expertise can have unforgivable consequences—people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed by police officers than are members of the general population and make up at least a quarter of those killed.

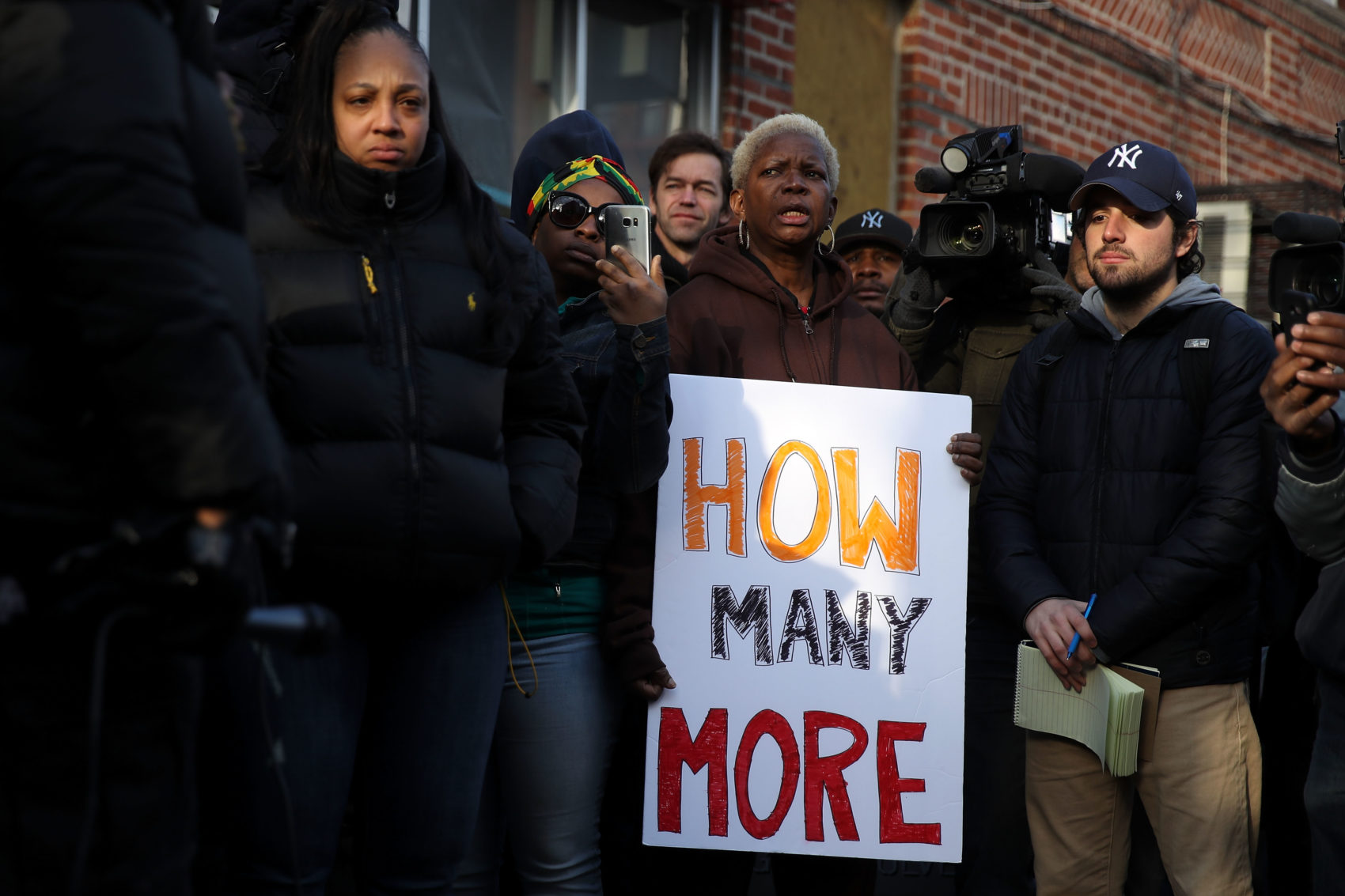

Writing in The Guardian in 2015, Mariame Kaba said, “Calling 911 should not be a death-wish,” and noted that too often, it is. In New York City alone, police officers who responded to calls for mental health crises have killed 15 people in the last three years.

In 2016, Deborah Danner was shot and killed by an NYPD sergeant in her own home. Officers went to her Bronx apartment after the building security guard called 911. There was no indication that the 66-year-old Danner was a danger to anyone. Yet, multiple NYPD officers followed her as she retreated into her bedroom and a sergeant eventually shot her twice in the stomach. The sergeant was acquitted at trial. The city reached a $2 million settlement with Danner’s sister.

The need for careful, qualified non-police emergency response measures continues to be urgent. In New York, emergency calls have nearly doubled in the last decade. Last year the NYPD received nearly 180,000 emergency calls about people experiencing mental health crises.

This week, the office of New York City’s public advocate, Jumaane Williams, released a report looking at the city’s police-heavy response to mental health emergencies. Williams has proposed an alternative—a non-911 number that people can call and a team of mental health counselors with the expertise to respond to a person in crisis. Williams also proposed an expansion in the use of mobile crisis teams, more funding for respite care centers, and the funding of mental health urgent care centers. The proposal also calls for increased crisis intervention training to police officers.

City & State New York interviewed five experts on policing and mental health crisis responses to get their reactions to Williams’s proposal. They were unanimous in their support for the need for a non-police service that would serve people in mental health crisis. Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College, referenced the United Kingdom’s approach, where mental health calls are largely handled by the National Health Service.

Like the public advocate’s office, the five experts also emphasized the need for the investments and services—such as supportive housing—that would address the root causes of many of these emergencies. Where they differed was in their assessment of whether a non-911 number, completely separate from police dispatchers, was necessary to achieve the desired result.

The proposal for New York City builds on successful efforts elsewhere. One of the best known is the Cahoots (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) program in Eugene and Springfield, Oregon. Cahoots has been getting attention in recent years for its design as a mental health response to mental health emergencies. When people call a non-emergency police number, the dispatchers determine whether Cahoots would be the appropriate response. If it is, a mobile crisis intervention team responds to all non-criminal crises, “including homelessness, intoxication, disorientation, substance abuse and mental illness problems, and dispute resolution.”

In surveys in overpoliced cities and neighborhoods, people are clear on the alternatives they would like to see. In 2014, the Oakland chapter of Critical Resistance conducted a community survey and found that people wanted more non-police options for emergency care, including during mental health emergencies. As TruthOut reported in 2015, community members overwhelmingly said they wanted healthcare resources “that aren’t connected to policing and alternative first-response models for emergency health crises.”

A more recent survey around community safety and policing conducted in Milwaukee revealed similar results. In its report of the survey results, the LiberateMKE campaign called on the city to fund non-police interventions for people in mental health crisis at an annual cost $4 million. “We demand that Milwaukee develop and fully implement a harm-reduction based program that can respond to people with unmet mental health needs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, without the involvement of law enforcement,” the report reads. “We further demand that it be housed in the city’s Health Department rather than the Police Department, and staffed by 100 health professionals.”

These survey responses reveal what should be obvious—that for too many, policing constitutes a threat, not a resource. In the New York Times this week, Marbre Stahly-Butts and Derecka Purnell argue that policing cannot be successfully reformed to serve as a solution to social problems: “After a movement against police violence erupted in 2014, scholars, nonprofit groups and politicians reimagined police officers as youth mentors, mental health professionals, and social workers—against the wishes of many police officers. But the police do not help vulnerable populations—they make populations vulnerable.”