Media Frame: Fentanyl Panic Is Worsening the Overdose Crisis

Sensational and false news reports about the drug are pushing lawmakers to enact harmful policies.

The public’s perception of crime is often significantly out of alignment with the reality. This is caused, in part, by frequently sensationalist, decontextualized media coverage. Media Frame seeks to critique journalism on issues of policing and prisons, challenge the standard media formulas for crime coverage, and push media to radically rethink how they inform the public on matters of public safety.

On June 4, the Senate Judiciary Committee gathered for a hearing to discuss legislation that would permanently place fentanyl analogues in the Schedule I category. The senators hoped the move would fight the spread of the potent opioid and its chemical offshoots that are driving the deadliest overdose crisis in U.S. recorded history.

Under federal law, a substance must be officially “scheduled” by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Food and Drug Administration in order to be deemed illegal. The five categories of drugs range from Schedule I to Schedule V. The government believes that Schedule I substances, like heroin, LSD, and MDMA, have no legitimate medical uses. Schedule V drugs are considered to have low potential for misuse and include low-dosage preparations of codeine, such as prescription cough medicines.

But because there are so many chemically similar derivatives of fentanyl, in 2018 the DEA made an emergency declaration that temporarily placed all unregulated fentanyl analogues into Schedule I, while urging China to tighten controls on manufacturers of the drug.

Both Democrats and Republicans at the June hearing supported the move and claimed it was responsible for a small decline in fatalities seen in provisional overdose data for 2018. But the law could not possibly have affected overdose rates because the fentanyl supply has not slowed.

No toxicological, medical, or addiction experts were present to testify at the hearing—just law enforcement, including witnesses from the DEA, Department of Justice, and the Office of National Drug Control Policy. And legislators used hyperbolic, unscientific rhetoric that mirrored the very worst of media coverage of the opioid crisis.

“It is a drug of mass destruction,” Lindsay Graham, chairperson of the Judiciary Committee, said during his opening statement. Graham’s speech eerily resembled a CNN piece in April that said illicit fentanyl poses a “national security threat,” and reported that top military officials are considering classifying the drug as “a weapon of mass destruction.”

Similarly, in a “60 Minutes” broadcast on April 28, Justin Herdman, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio, pointed to an evidence bag containing white powder and said, “This is essentially enough fentanyl and carfentanil to kill every man, woman, and child in Cleveland.” Though fentanyl is an extremely potent opioid, illicit fentanyl seized off the streets by law enforcement, which is concocted by chemists in unregulated labs, is more akin to bathtub gin and is unlikely to be 100 percent pure. Without testing the purity of the illicit fentanyl, who knows how many people it would kill? But in order to make the case for militarized drug enforcement, politicians and law enforcement officials foment the idea that illicit fentanyl is dangerous not just for people who snort and inject it, but also for innocent bystanders who do not even use the drug.

Cleveland’s Lutheran Hospital probably also has enough fentanyl to kill everyone in the city, but that isn’t a news story because doctors and anesthesiologists safely use it on patients every single day. Though pharmaceutical fentanyl is far different than illicit fentanyl, which is typically sold as heroin, neither is a doomsday weapon.

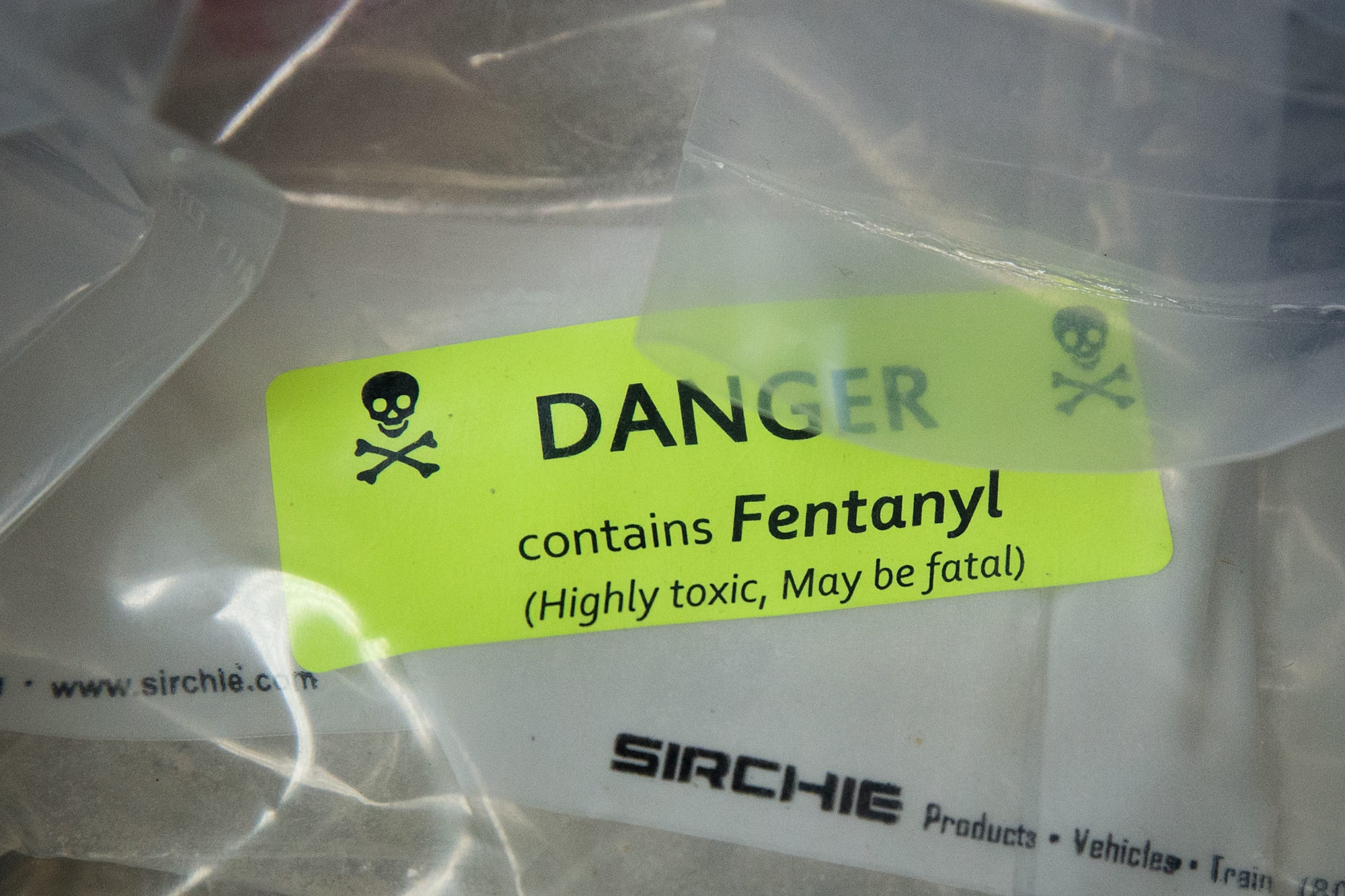

Another falsehood peddled by the media about fentanyl is that touching the drug can result in an overdose. In the same “60 Minutes” segment, Scott Pelley asked Herdman, “So, if you touch this stuff, it could kill you?” Herdman responded, “Yeah. There’s a reason why we have a medic standing by, Scott, and that’s because, unfortunately, it’s something that we have to be prepared for, even dealing with it in an evidence bag.”

But standing next to a bag of illicit fentanyl, or even touching the drug, is highly unlikely to lead to an overdose because the molecule is not skin-soluble. It took pharmaceutical companies years of research and millions of dollars to create a fentanyl patch that slowly releases a dose of the drug over time through a skin matrix. In 2018, harm reduction activist Chad Sabora filmed himself putting illicit fentanyl on his skin to debunk the notion that touching powder fentanyl is toxic.

“60 Minutes” has not corrected its mistaken claim that fentanyl is deadly to the touch, even though not a single accidental exposure story has been verified with toxicological testing. On March 16, the news outlet VTDigger reported that a Vermont state trooper supposedly had to be revived with multiple doses of naloxone, the overdose reversal drug, after being “exposed” to heroin during a routine traffic stop that turned into a minor drug bust. Four days later, the publication ran a follow-up article correcting the record, but it did not receive anywhere near the attention of the original report, which was picked up by the Associated Press and circulated to ABC, NBC, and a slew of regional news outlets. Like fentanyl, heroin cannot be absorbed through skin contact.

Although the American College of Medical Toxicology released a statement in 2017 explaining that touching illicit fentanyl does not carry significant risk, local news outlets continue to churn out stories of police officers administering naloxone to themselves and their colleagues after feeling “dizzy” and “lightheaded” at the scene of minor drug busts and overdose calls. (These are not symptoms of opioid overdose—they are the symptoms of panic.)

Take the June 2018 case of “fentanyl-laced flyers” left on the windshield of a squad car that made an officer feel vaguely ill. USA Today and other publications ran articles about the flyers causing overdoses, solely based on a police department press release. After toxicological testing, the Houston Chronicle reported that there was indeed no fentanyl on the flyers. Again, the follow-up reporting received little attention.

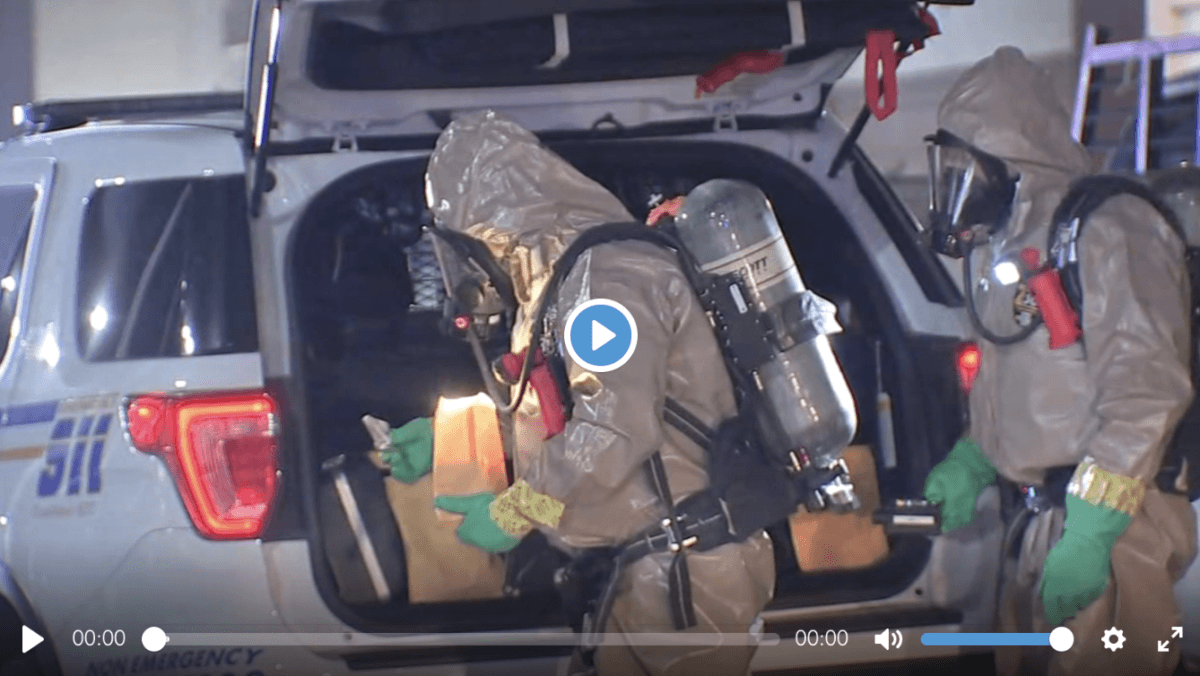

On June 13 of this year, an ABC affiliate in Houston reported that two sheriff’s deputies “began to feel ill” while collecting drugs in a hotel room that were first spotted by its cleaning service. After the officers administered naloxone to themselves, which in an actual overdose would be physically impossible because the victim would be unconscious, a hazmat team swarmed the hotel. A minor drug bust then turned into a scene out of HBO’s “Chernobyl” miniseries. No one bothered asking why the cleaning staff that found the drugs did not share the strange symptoms of the sheriff’s deputies.

Ryan Marino, an emergency medicine physician and expert in medical toxicology, is the kind of person who should be—but rarely is—quoted in such stories. “I have essentially zero concern about fentanyl for myself personally, and have never encountered an issue in working with people who use fentanyl or who have overdosed on fentanyl,” Marino told The Appeal. “Policymakers seem to have taken this urban legend to heart, and are using it as an excuse to divert resources away from evidence-based and lifesaving interventions (like naloxone) and toward idiotic and wasteful things like full hazmat gear for law enforcement to conduct routine traffic stops.”

Marino continued, “In my line of work, I have unfortunately seen people who are not appropriately resuscitated after an overdose—where every second counts—because of the fear of fentanyl contagion.” Marino said that fear of fentanyl exposure may delay rescue breathing, which can mean the difference between life and death—or complete recovery versus severe brain damage—during an overdose.

Sensational coverage of drugs like fentanyl carries real consequences—and not just for journalism, but for policy making. During the June hearing, Senator Graham said that “EMTs, police officers, and other first responder types have been injured—some have died!–– treating fentanyl abuse cases.”

Legislation that would permanently schedule all fentanyl analogues has bipartisan support, but there is little evidence that scheduling changes reduce drug-related harm. This move would also do little to save the lives of people who are addicted to the drug today. In the mid-1980s, media panic over crack and overly punitive politics from both political parties led to the Anti-Drug Abuse Acts of 1986 and 1988, which mandated a 10-year sentence for anyone caught with 50 grams of crack. A dealer selling powdered cocaine would have to be caught with 5,000 grams to get a comparable sentence, a 100-to-1 disparity between the two forms of what is effectively the same drug. In 2010, Congress enacted the Fair Sentencing Act which reduced the sentencing disparity between offenses for crack and powder cocaine to 18 to 1.

And panic around young people doing MDMA in nightclubs led to the drug being classified as Schedule I, which has hindered research into its potential utility in treating post-traumatic stress disorder.

Fentanyl and its many derivatives are causing far too many people to die prematurely. But spreading misinformation and hyperbolic claims about drugs creates a climate of fear and a rush to judgment. It also leads us down the road of failed policies that continue to criminalize people, rather than prompting recovery.

Zachary Siegel is a freelance journalist in Chicago and a member of the Changing The Narrative collective. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Slate, and Wired, among others.

Maia Szalavitz is a co-founder of the Changing the Narrative collective and the author of the New York Times bestseller Unbroken Brain: A Radical New Way of Understanding Addiction. She has written on neuroscience, drugs, and addiction for numerous publications, including High Times, Vice, the New York Times, and Scientific American.