How Deep is the Scandal at Maryland’s Medical Examiner Office?

The state launched an investigation after the former chief medical examiner’s biased testimony in the George Floyd murder trial. Now, an Appeal analysis finds major flaws in the probe’s design.

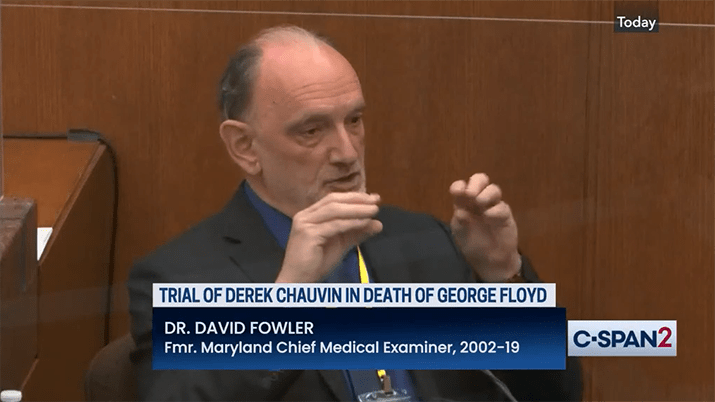

On April 14, 2021, Dr. David Fowler, Maryland’s former longtime chief medical examiner and one-time president of the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME), took the witness stand and testified that Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was not responsible for George Floyd’s death.

While many had seen cell phone video of Chauvin pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes and concluded, as a jury ultimately would, that these actions had killed Floyd, Fowler disagreed. Instead, he testified that Floyd’s death might have been caused by some combination of a heart condition, intoxicants, and exhaust from a nearby car. He concluded that he would have ruled Floyd’s manner of death “undetermined” instead of “homicide.”

Fowler’s testimony ignited an immediate outcry. Although he had retired as chief of Maryland’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) in 2019, after leading it for 17 years, questions swirled about his pro-law enforcement bias and how it might have impacted his office’s review of other police killings in the state.

On Sept. 9, 2021, Maryland’s Office of the Attorney General (OAG) announced an audit into OCME under Fowler in partnership with the governor’s legal counsel. Over a year later, OAG stated that the audit would review approximately 100 selected in-custody deaths, with particular attention to those that “occurred during or shortly after the decedent was physically restrained and for which no obvious medical cause of death … was discerned”—in other words, cases that resemble Floyd’s. Expert auditors have been tasked with determining if the cause and manner of death findings in these cases were based on “adequate investigations.” The probe also promised to determine if changes are needed to “improve the OCME’s practices.”

Three years after the initial announcement, progress has lagged as the public has been kept in the dark. In an email to The Appeal, OAG has declined to share any information about the specific cases the audit is examining or when they expect to complete the review. Fowler did not respond to an email request for comment.

While the public awaits answers, an investigation by The Appeal into in-custody deaths in Maryland suggests there is significant reason to be skeptical about the scope of the audit and its ability to provide an accurate accounting of OCME bias under Fowler.

Our investigation included an analysis of an OCME database of 1,313 in-custody deaths in Maryland between 2003 and 2020, from which the audit’s 100 cases were selected. We also examined autopsy reports from more than 50 of these cases. We chose cases with clearly questionable findings, like “excited delirium,” as well as publicly known cases and several selected randomly. Where available, we examined police and court files in those cases.

The Appeal’s analysis found that medical examiners routinely employed biased methods, returned scientifically unfounded findings, and relied on unorthodox reporting processes, among other issues. These findings point to systemic issues of pro-law enforcement bias that extend far beyond the seemingly arbitrary selection of approximately 100 cases.

‘Undetermined’ Findings Shaped by Police

Tawanda Jones began publicly raising concerns about OCME’s bias in 2013 after the office determined police were not responsible for her brother Tyrone West’s death. Two independent autopsies contradicted OCME’s finding, determining that he was killed as a result of “positional asphyxia,” or face-down choking by officers. Before Fowler’s testimony in Chauvin’s trial, there was little public recognition of the issues Jones was raising about OCME.

“Finally, the truth is out, but why couldn’t you guys take the truth when I’m giving you the truth?” Jones told The Appeal.

West’s official autopsy report offers a case study of one of OCME’s most problematic practices: The report has a long and speculative “opinion” narrative based almost entirely on information sourced directly from police reports. “Per forensic investigation,” the narrative says, “the decedent was operating a car when he was stopped by two police officers. He exited the vehicle, sat down on a street curb and reportedly struck one of the officers as the officer approached him.”

This detail is not relevant to West’s medical cause of death. Its presence in the autopsy report serves as a seeming justification for why officers subsequently beat him with batons and restrained him forcefully. There was no video footage to verify that West struck an officer.

Autopsy report formats vary across jurisdictions but are usually limited to medical findings. The “opinion” section is supposed to summarize the cause and manner of death. After Sandra Bland died in a jail cell in Waller County, Texas, the autopsy report’s opinion stated: “Cause of death: hanging. Manner of death: suicide.”

In Maryland, autopsy opinions tend to be shorter and more scientific when the case seems more straightforward. For instance, in the 1999 murder case of Hae Min Lee, of “Serial” podcast fame, the opinion is four sentences. Of the 24 in-custody death autopsy reports reviewed by The Appeal with an “undetermined” or “accident” finding, almost all have long, detailed opinion narratives, many running up to a page or more.

These longer opinions sometimes draw word-for-word from the statements and reports of police on the scene—often from officers who are literally suspects in the deaths, as in the West case. Police narratives are seamlessly woven into what is otherwise presented as medical fact, then signed by a forensic pathologist, a medical doctor.

According to national guidelines, medical examiners are supposed to work independently of law enforcement. Dr. Victor Weedn, a former OCME medical examiner who briefly ran the agency after Fowler’s departure, said the office didn’t always meet this expectation.

“I think Maryland probably did defer to the police a little too much,” he told The Appeal in an interview. “And I don’t think they were trying to be prosecutorial in their attitude or bias, but I think they were.”

OCME’s opinion narratives often characterize victims poorly, citing their criminal records and unwillingness to comply with commands while crediting police for using “standard acceptable guidelines” for restraint or Taser usage. Weedn considers these kinds of statements inappropriate. “It’s the wrong question. Because you could use the appropriate use of force, and people still die,” he said.

Dr. Itiel Dror, an expert on bias in the forensic sciences who participated in the team that designed the OCME audit, told The Appeal that he asked an OCME representative at a panel meeting if the agency handled the bodies of people who “died in police custody” differently than other bodies.

“Do you do different tests? Do you treat it differently?” he recalled asking. “And she said, ‘Yes, we do it differently.’”

OCME’s deputy chief medical examiner, Dr. Pamela Southall, conducted West’s autopsy in 2013. During a deposition in a wrongful death suit filed by West’s family, she admitted that police detectives attended the autopsy examination and informed her narrative. Case files and multiple sources confirm this has been common practice at OCME.

Weedn recounted a meeting at which Southall informed OCME staff that medical examiners should “listen to the police officers to determine whether they thought there was some problem” in how suspects were handled during in-custody death cases. Southall did not respond to an email requesting comment.

While OCME’s opinion narratives lean heavily on police input, they also routinely exclude accounts from civilian witnesses. Sometimes, this is a deliberate choice; during Southall’s deposition in the West case, she admitted to reviewing and not including witness statements. But in other cases, police simply do not provide OCME with the information.

After Freddie Gray’s 2015 death in police custody, OCME was not given the recorded statements of numerous witnesses who saw police remove Gray from the van around the corner from his arrest, shackle his legs, and throw him headfirst back into the vehicle, after which he became silent and motionless. The medical examiner’s unusually dense, three-page opinion is filled with uncertain language, like “possibly” and “likely,” and guesses that his “headfirst” injury happened while the van was in motion.

As Weedn explained, “Sometimes the police are cooperative, and sometimes they’re not” when it comes to providing OCME with video or other evidence. “You can do a little bit of your own investigation, but… we don’t do homicide investigations.”

In an email to The Appeal, OAG confirmed that the investigators auditing OCME files will be relying on the same information medical examiners used in their analyses. Without access to complete police files, reviewers may be more likely to draw the same conclusions, undercutting the audit’s promise to provide an independent assessment.

Excited Delirium, in Other Words

With a focus on cases involving police restraint and “no clear medical cause of death,” the audit is likely to examine OCME’s historic use of “excited delirium” as a cause of death.

Excited delirium syndrome is a widely discredited cause of death explanation with racist origins and no concrete definition. It hinges on the idea that mental illness or extreme agitation can cause a heart attack in the presence of authority, especially when paired with pre-existing medical conditions or drug use. The condition is not accepted by any leading medical group, and a handful of states have sought to ban its use.

The database of 1,313 Maryland in-custody deaths lists only the official cause and manner of death for each case. In 35 of those cases, the cause of death was ruled as some form of “excited” or “agitated” delirium or state. In almost all of these, a medical examiner concluded that the manner of death was “undetermined.” Yet, OCME’s practices suggest there could be hundreds more cases with cause-of-death rulings based on the theory of excited delirium, even if medical examiners did not specifically code them that way.

Fowler and Southall have published articles on excited delirium, and, in some cases, it appears to have been a default assumption at OCME. In 2015, Darrell Brown went into cardiac arrest minutes after police tased him. A sheriff’s office investigator attended the autopsy the next day and wrote in his notes that the medical examiner had “advised that she is familiar with the use, procedures, and effects of the Taser device (Conducted Electrical Weapon) and also very familiar with excited delirium.” Despite witnesses who saw Brown collapse after being tased, the ME ruled his cause of death as drug “intoxication induced excited delirium.” OAG has declined to clarify whether the audit will include the numerous Maryland in-custody deaths involving tasing.

Fowler, who obtained his medical education in South Africa during apartheid, has stated that he does not believe tasing or “positional asphyxia” are legitimate cause-of-death findings. In his testimony in the Chauvin case, he cited researchers in San Diego whose controversial findings claim to disprove that face-down police restraint can be deadly. Weedn recalls those researchers being influential at OCME and visiting the agency’s office.

The Appeal’s close review of autopsy reports included 28 excited delirium cases, all of which involved subjects becoming unconscious during or right after being tased or placed in a face-down restraint (or a “spit hood” over the head, in one case).

There are striking similarities across the autopsy reports for these cases. Medical examiners routinely make use of racist tropes, drawing language directly from police reports. Many of them describe subjects as entering a “trance-like” state, taking on “superhuman” strength, sweating, and making “animal-like noises,” as the medical examiner wrote in Brown’s case. A police sergeant at the scene who ordered his officer to tase Brown described him as becoming like “The Incredible Hulk.” Language like “growling,” “barking,” and “grunting” appears across these reports. The prevalence of these phrases in police reports suggests officers have known which type of language will elicit an excited delirium finding.

Medical examiners consistently place delirium first on a ranked list of contributing causes of death and police force last in these autopsy reports. In many cases, they list out all pre-existing medical and mental health conditions before listing bodily injuries. Most excited delirium autopsy reports include up to a page or more of fresh injuries, including contusions, hemorrhages, and Taser marks.

The excited delirium cause of death ruling is a national problem, which some groups are seeking to abolish. These include Campaign Zero, a police reform organization that contributed to this article by ordering autopsies and police reports. In 2023, NAME officially recommended that medical examiners stop using excited delirium as a ruling.

Yet, even if OAG has included all of the database’s 35 delirium cases in its audit, it wouldn’t fully address the number of OCME cases influenced by the theory of excited delirium. Under Fowler, OCME began using the term “delirium” less frequently in the mid-2010s, “as it became more controversial,” Weedn suggested. But the office may have found other ways to conclude essentially the same thing.

In 2018, OCME determined that 19-year-old Anton Black had died from “sudden cardiac death” after an arrest that September on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Witness statements and police body camera footage showed officers putting Black in a prolonged face-down restraint, during which he lost consciousness.

The autopsy opinion cites “the stress of his struggle” and Black’s bipolar disorder as contributing factors to his death, which a medical examiner attributed to “anomalous right coronary artery and myocardial tunneling of the left anterior descending coronary artery.” It also claims that Black “may have recently smoked ‘spice,’” a synthetic cannabinoid, directly contradicting two toxicology reports that were negative for all substances. Black was an athletic and otherwise healthy teenager, and myocardial tunneling is “common and generally benign,” according to the American College of Cardiology.

Similarly, West’s autopsy report, written nearly five years earlier, identifies the primary cause of death as “cardiac arrhythmia due to cardiac conduction system abnormality complicated by dehydration,” or an electrical problem with the heart. His family has insisted that he was healthy before his fatal encounter with police. The opinion narrative cites the high temperatures that day as contributing to West’s death, as well as his “adrenaline” and aggressiveness.

Both the Black and West cases offer examples of OCME attributing deaths involving police restraint to spontaneous cardiac events prompted by mental agitation—essentially “excited delirium,” in other words. When Fowler testified for the defense in Chauvin’s trial, he did not mention “excited delirium” directly. But he did cite “adrenaline” and the “fight or flight” response, which are common excited delirium tropes.

OCME’s propensity to obscure excited delirium-type findings behind cardiac conditions also appears in cases where medical examiners have attributed the cause of death to drug use. After several people witnessed Tawon Boyd die in 2016 during face-down police restraint, an OCME medical examiner determined his primary cause of death was an “accident” caused by “complications of N-ethylpentylone intoxication,” a synthetic stimulant. The autopsy opinion narrative even mentions Boyd being in an “excited delirium-like state,” with commonly associated tropes, calling him “paranoid,” “crazy,” and “sweating profusely.”

Given OCME’s documented patterns in these and other cases, it’s clear that the audit cannot get a complete picture of the influence of “excited delirium” under Fowler without examining all in-custody deaths attributed primarily to cardiac events and drug use. Nearly 300 in-custody death cases in the database identify some kind of cardiac failure as the official primary cause of death, and nearly 200 identify intoxication.

‘Natural’ Deaths and Suicides?

Based on the audit’s stated criteria, it is likely to exclude most of the OCME database’s 272 in-custody deaths ruled suicides and 399 deaths ruled to be from natural causes. The autopsy report opinions for these cases tend to be short and succinct, leaving less room to identify clear and obvious bias. But that doesn’t mean they are non-controversial.

Tyree Woodson was found dead from a gunshot wound inside a police station in 2014. OCME determined, with input from police, that Woodson used his own weapon. Yet, officers said they had searched Woodson for a gun before entering the station. Families have questioned the accuracy of reports ruling deaths in Maryland jails and prisons to be suicides, especially after reports finding that some have seen higher-than-average numbers of suicides.

There is also cause for further review of so-called “natural” in-custody deaths. OCME has attributed many police-involved deaths to all sorts of pre-existing illnesses, including ulcers, hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), carcinomas, fungal infection, and sickle cell trait, a mostly benign blood condition more common in Black people that, like excited delirium, has been historically used to excuse police killings.

In 2014, OCME determined that George King died a “natural” death at the hospital from “meningitis and an abscess in his spine.” But his death came shortly after police repeatedly tased him while attempting to restrain him to a hospital gurney.

Also of serious concern is the extraordinary number of jail and prison deaths that OCME has determined are “natural.” A 2023 study of deaths in 10 Maryland jails concluded there has been “widespread misclassification of deaths attributable to violence and/or negligence.” The study found that incarcerated people were dying supposedly “natural” deaths at ages substantially below “life expectancy among the non-jailed population.” Of the cases analyzed, about half “died within 10 days of their admission,” while “more than one-sixth died less than two days after their admission.”

In an interview with The Appeal, Terence Keel, director of the Biocritical Studies Lab, which conducted the study, explained that under official NAME guidelines, a natural death is “supposed to occur generally at the end of one’s life, usually as a result of illness and disease.” He questioned whether anyone could die a truly “natural” death behind bars, considering all of the environmental factors that could contribute.

“If the state were really invested in cleaning up the medical examiner system, it would do a comprehensive look at all these cases,” Keel said.

Limited Impact

As OAG’s investigation inches towards its conclusion, questions remain about conflicts of interest among the probe’s leadership. If the audit were to show that OCME had routinely covered for police who kill, it could expose the state to substantial liability in many cases. The officials overseeing the audit—the governor’s legal counsel and OAG, which often represents the state in lawsuits—would likely prefer to limit the potential fallout.

They have “a dog in this fight,” said Latoya Francis-Williams, a Maryland attorney who has handled police brutality cases. “They do not want to open those floodgates.” She added that she believes state officials are only conducting a limited audit as a gesture to “appease the community that’s complaining” about OCME.

Even Dror, who participated in the team that designed the audit, admits that the audit won’t be comprehensive. “Maryland is starting with one hundred or so cases because they need to start somewhere,” he said. He described the audit as a “first step” and “the tip of the iceberg,” though he said it’s unlikely the state will investigate further.

“If those 100 cases show the bias… then you don’t need to look at more cases,” said Dror. He insisted that OCME’s issues under Fowler are not an example of a “bad apple” but rather a reflection of a national problem of pro-police bias among medical examiners.

It remains to be seen whether the audit’s findings will be used to change practices at OCME. Either way, the investigation seems unlikely to provide any resolution in the more than 1,200 in-custody death cases that were not audited. The burden will remain on families to hire lawyers or independent medical examiners to find relief or justice in those cases.

“They screwed over more than [just those] 100 families,” said Tyrone West’s sister, Tawanda Jones, referring to the cases selected for the audit. “It’s almost like somebody’s trying to clean up a dirty, funky house with air fresheners.”

Jones says OAG should expand the audit to all of the database’s 1,313 death-in-custody cases. But even that number may not be exhaustive. Maryland law doesn’t require OCME to specifically categorize in-custody deaths, which makes it almost impossible to know the total number of affected cases.

In an interview with The Appeal, Bruce Goldfarb, the former OCME public information officer tasked with compiling the database of in-custody deaths for OAG, explained that he used a grueling and admittedly imperfect process to find cases. This included running keywords through OCME’s system and using social media to track down relevant deaths. Some known cases are missing from the database, though, including George King and Trayvon Scott, who allegedly died of an asthma attack in police custody in 2015.

Deaths in law enforcement custody may also not be the only cases deserving of further scrutiny. Baltimore journalist Stephen Janis has reported extensively, for more than a decade, on dubious OCME findings under Fowler. This includes the cases of two people who were found dead at the bottom of a garbage chute in the same building just a year apart. OCME determined that one fell down the chute accidentally, and the other jumped in a suicide.

OCME has already agreed to some reforms as part of a November 2023 settlement with the Black family, which sued the agency and Fowler. These include following NAME guidelines for classifying most death-in-custody cases as homicides, working independently from law enforcement, and documenting all investigative information and personnel present at autopsies. OCME did not respond to emailed questions on how it is instituting these changes.

While the reforms seem like positive steps forward, police could complicate these efforts by sharing even less information with OCME. OCME could also continue its shift toward hiding the role of police force behind drug use and medical conditions. Fowler is no longer in office, but many medical examiners who worked under him still are.

Ultimately, substantial change would involve reducing the influence of OCME’s “opinions” in the courts. In other developed countries, medical examiners do not testify in criminal cases as to the manner of death, preventing judges and juries from relying too much on their conclusions in making legal determinations.

In the meantime, attorney Francis-Williams describes an uphill, case-by-case battle over years to “re-educate” judges, juries, and the public that autopsy conclusions are not always “objective and scientific.”

“That’s certainly not the name of the game when it comes to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner,” she said. “Definitely not.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the year in which NAME called on medical examiners to end the use of excited delirium as a cause of death. We have updated the copy to reflect that NAME issued its recommendation in 2023. Several other minor copy errors have also been addressed.