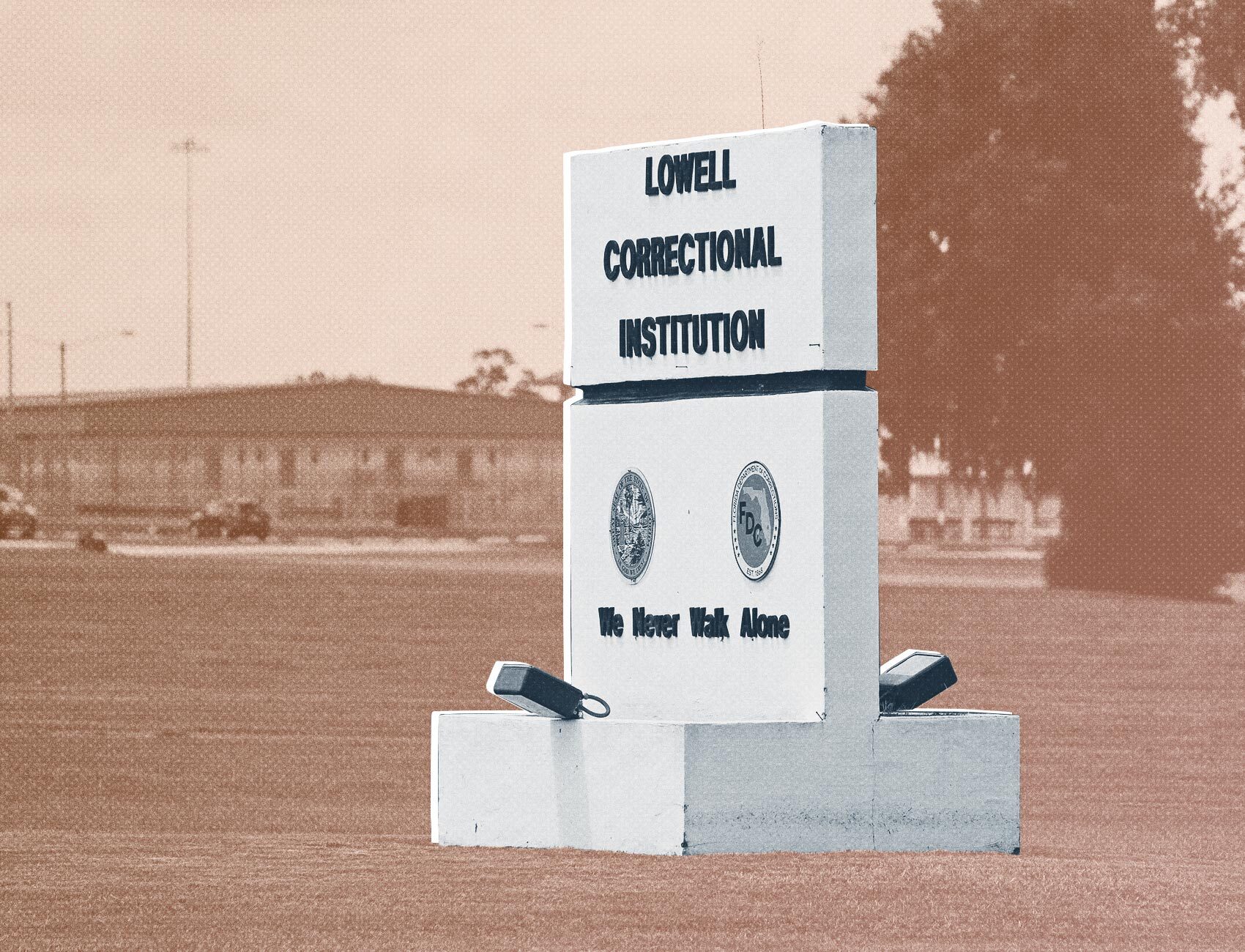

Loved Ones And Prisoners Sound Alarm As Coronavirus Cases Surge At Florida’s Largest Women’s Prison

As of Thursday, 993 incarcerated women and 62 staffers at Lowell Correctional Institution have tested positive for the virus. Two women have died.

Nearly a month had passed since Kenyetta heard from her sister at Lowell Correctional Institution in Florida when she received a message in late July. Her 37-year-old sister, who has Type 2 diabetes and latent tuberculosis, wrote to tell Kenyetta that she was battling a severe headache and sore throat. Her body, she said, felt like it had been in a car wreck.

In the July 27 message, Kenyetta’s sister told her that Lowell had just accepted a transfer of incarcerated women from the Florida Women’s Reception Center. The newly arrived women, who were promptly moved into the main unit near Kenyetta’s sister, were released from what was ostensibly a 14-day quarantine for exposure to COVID-19.

“These new ppl came in coughing and sneezing,” wrote Kenyetta’s sister, who is serving a 15-year sentence at the Marion County prison for robbery with a deadly weapon. Kenyetta asked The Appeal not to name her sister—and to withhold her own last name—for fear of retaliation from the prison staff.

Three days after the women arrived at Lowell, Kenyetta’s sister and the others in the dorm—all of whom were previously healthy—fell ill, she said in the message. On Aug. 14, she was confirmed positive for the novel coronavirus. In an email to The Appeal, the Department of Corrections neither confirmed nor denied the transfer, stating only that noncritical transfers have been paused statewide since March and all transfers into and out of Lowell were temporarily suspended in early August.

Kenyetta said she’s now anxiously waiting to hear how her sister is coping with the infection. But as she watches the surging cases at the prison, which has long been plagued with reports of abuse and medical neglect, Kenyetta can’t help but feel powerless.

“She has 10 more years to go,” Kenyetta told The Appeal. “I want to see her. I want her to come home.”

As of Thursday, 993 incarcerated women and 62 staffers at Lowell have tested positive for COVID-19. Two women have died. The prison is listed as No. 16 on the New York Times’s list of largest clusters of the virus in the U.S. It ranks closely behind the Smithfield Foods pork processing facility in South Dakota, which was once considered the largest coronavirus hotbed in the nation.

In March, before the first case of the virus was confirmed inside Florida’s state prisons, advocates sounded the alarm that Lowell wouldn’t be able to navigate a widespread outbreak. The state’s largest prison for women is home to nearly 500 women over the age of 50. The massive complex also has a dorm specifically for prisoners who are elderly, pregnant, or have complex medical needs.

As the virus has coursed through Florida’s state prisons—infecting more than 15,000 and killing 78 as of Thursday—advocates and state leaders have called on prison leaders and Governor Ron DeSantis to consider compassionate release for certain people. They’ve been asked to review all elderly and vulnerable prisoners and suspend sentences through commutations or pardons. But to date, calls for action have fallen on deaf ears.

In a virtual press conference Aug. 13, state lawmakers reiterated their demands. Representative Dianne Hart called out the persistent lack of action from the top, noting that state corrections leaders have yet to take any steps to release a portion of the state’s 100,000 prisoners. No prisoners from Lowell have been granted compassionate release since the pandemic arrived.

According to the Palm Beach Post, at least 14 state prisoners who have succumbed to the virus were eligible for parole.

For months, the DOC has touted a long list of measures it is taking to protect prisoners, including its pledge to conduct daily temperature checks, suspend prisoner transfers and provide “on-going medical care and monitoring” to prisoners, according to its website. Kenyetta told The Appeal, however, that her sister has only received temperature checks a few times each week.

Similar accounts have been echoed in messages recently sent to Debra Bennett-Austin, a former Lowell prisoner and founder of the nonprofit Change Comes Now. In an Aug. 12 message, one woman at Lowell’s Main Unit wrote to her: “We are not being temp checked at all….. there are several girls that have been showing symptoms, but no nurses are available…. even for a medical emergency.”

Another woman at Lowell Work Camp wrote on Aug. 12: “They still do not take our temperature every day. Monday and Tuesday no one came to take it. Today when the nurse came she didn’t write down anyone’s temps and didn’t seem to care what the thermometer read.”

In a statement to The Appeal, the DOC wrote that “inmates in medical quarantine are monitored by health services staff and receive temperature checks twice a day for signs of fever.” The agency did not respond to questions about prisoners outside of medical quarantine not receiving temperature checks.

Sue Kuhns’s girlfriend, who is set to be released from Lowell in November 2021 and has lupus, told Kuhns that she has been spending the majority of her days on her bed, trying to keep as much distance from others as possible. She learned that she was negative for the coronavirus on Aug. 11, nearly two weeks after getting tested on July 27, Kuhns said.

Kuhns’s girlfriend, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation from prison staff, told Kuhns that staffers at Lowell have been cross-contaminating people on the compound, bringing women who may have been exposed to the virus into healthy dorms with no explanation. Kuhns’s girlfriend also told her that when other women in her dorm began feeling sick, the medical staff waved it off as summer colds.

“Medical emergency? You might as well cancel Christmas on that,” Kuhns told The Appeal. “You gotta be dead just about before they’ll come to help.”

In their near-daily conversations, Kuhns’s girlfriend has described the increasingly desperate conditions at Lowell: women hoarding food, books, and other items, fearful of the unknown. She tells Kuhns that between the level of stress and heat at the prison, which has many dorms without air conditioning, people have become irritable.

“Everything is really tense and people are really scared,” Kuhns’s girlfriend wrote in a July 23 message to her. “It’s like the life lottery. Who gets to live?”

Kuhns said her girlfriend emphasized how the outbreak has worsened the nutritional quality of the food, given that prison meals now have to be delivered to dorms and canteen access has been restricted. Kuhns said she has described subsiding on a monotonous diet of bread with peanut butter or bologna, rarely knowing when her next meal is going to come.

“It’s a tablespoon, if they’re lucky, of peanut butter, two slices of bologna, some cheese, carrot coins, shredded carrots,” Kuhns said. “And the ones that don’t have teeth, they’re out of luck.”

Similar reports have emerged from Homestead Correctional Institution, a women’s prison located roughly five hours south of Lowell. In an email to The Appeal, the DOC wrote that it is following a dietary reference from the National Academies of Science “to ensure proper nutrition and caloric intake for inmates.” The modified menu available to prisoners was designed by dieticians to “meet standards” and “provide the required nutritional content,” the DOC stated. However, it didn’t deny accounts of prisoners getting by on bread with bologna or peanut butter.

According to the DOC, prisoners at Lowell continue to have access to the canteen through individual orders. But Kuhns said her girlfriend hasn’t been able to purchase anything from the canteen since the pandemic began, despite filling out two order forms for various items. Kuhns worries that her girlfriend, already immunocompromised, won’t be able to fend off the virus while sustaining herself on the available diet.

“I mean, she’s getting worn out and tired. She needs some nutrition,” Kuhns said. “How are they supposed to keep their energy up, if you’re feeding them the same thing over and over and over?”

Lately, Kuhns has been eating peanut butter sandwiches and bologna in solidarity with her girlfriend and the other women at Lowell. But like so many others with vulnerable loved ones incarcerated across the state, Kuhns is scared. She wants her girlfriend, whose scheduled release is lingering on the horizon, to be granted compassionate release.

“She’s got 15 months, you know,” Kuhns said. “If they’ve got 18 months or less, release them. Get an ankle monitor on them. She’s safer here at home than she is in there.”