Louisiana Prosecutor Testifies in Favor of Jury Law Rooted in White Supremacy

What I am about to tell you is deeply problematic. And it makes sense that of all states, it’s happening in Louisiana — which, with its sky-high incarceration rate, is the “world’s prison capital.” According to local reports, a staggering “one in 86 adult Louisianians is doing time, nearly double the national average. Among black men from New Orleans, […]

What I am about to tell you is deeply problematic. And it makes sense that of all states, it’s happening in Louisiana — which, with its sky-high incarceration rate, is the “world’s prison capital.”

According to local reports, a staggering “one in 86 adult Louisianians is doing time, nearly double the national average. Among black men from New Orleans, one in 14 is behind bars; one in seven is either in prison, on parole or on probation.”

Louisiana holds the horrible title of the world’s most incarcerated state in part because it pays local sheriffs a per diem to house inmates, who greatly rely on those payments to fund their departments. So the sheriffs are incentivized to house as many people as they can for as long as they can.

The other part of this story is something I must confess that I did not know until a few months ago. In 48 states, and in federal trials, all 12 jurors agree on the guilty verdict in order for a defendant to be convicted of a crime. In both Louisiana and Oregon, only 10 out of 12 jurors have to agree on a guilty verdict in felony cases. In Louisiana, non-unanimous verdicts are allowed in murder cases — but Oregon still requires a unanimous vote to find defendants guilty of murder. In those two states alone, two people on a jury could be absolutely convinced, deadlocked and unmovable, of a defendant’s innocence, and that defendant could still be sent to prison for the rest of their natural life. In fact, this very thing has happened many times in both states. In late 2016, Cardell Hayes of New Orleans was convicted in what his defense team claimed was a self-defense killing of a former New Orleans Saints football player — even though two of the 12 jurors dissented. In April 2017, Hayes received a 25-year sentence from the judge.

Now, here’s the worst part: The non-unanimous jury law in Louisiana has its roots in post-Reconstruction era white supremacy. Indeed, the non-unanimous jury rule was formally adopted as law during the state’s 1898 constitutional convention. There, lawmakers said that their “mission was … to establish the supremacy of the white race.” Over a century later, non-unanimous verdicts are a tool to perpetuate mass incarceration and racial oppression.

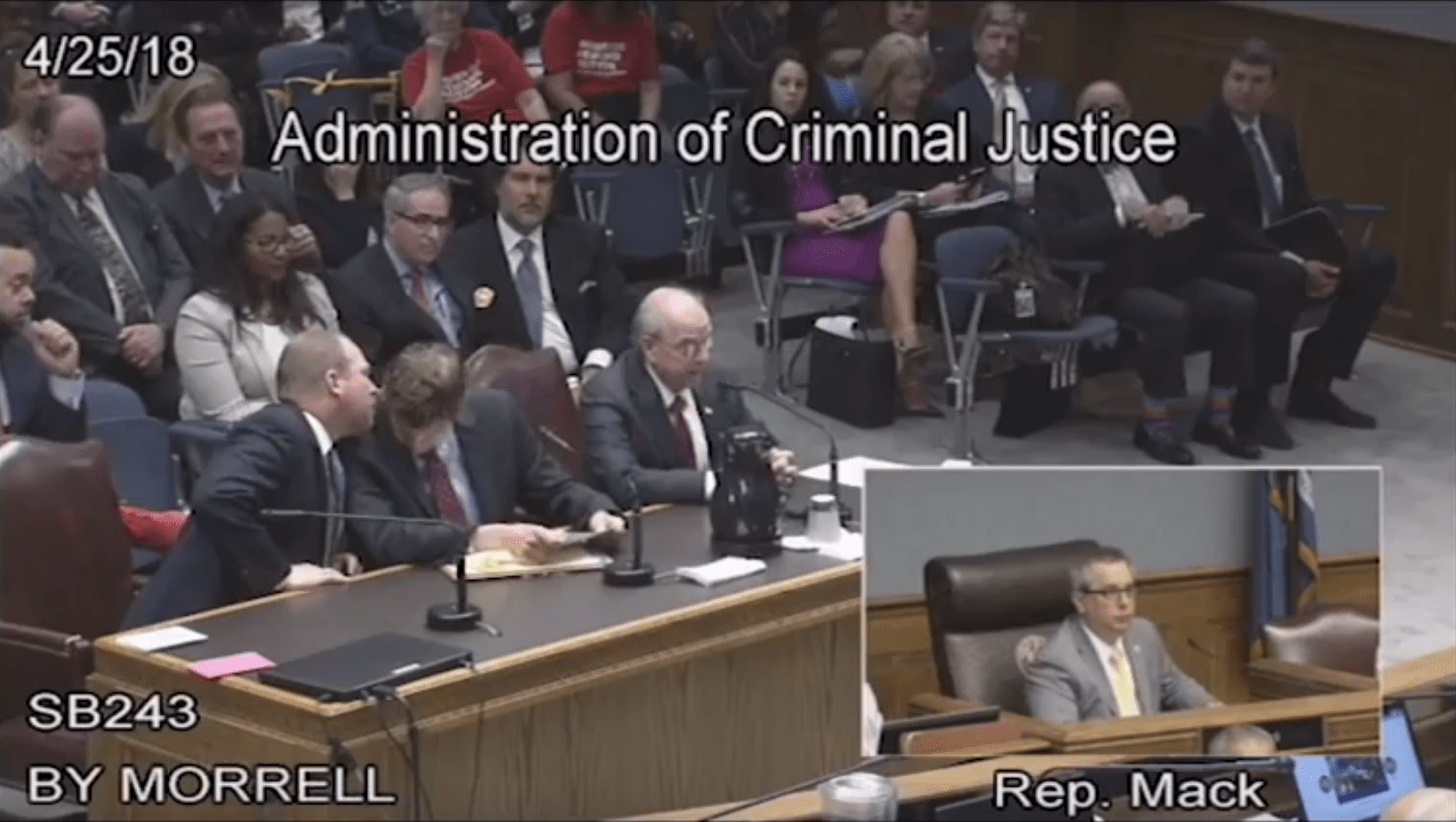

As early as today, however, Louisiana could reverse course and join the rest of the nation by requiring unanimous guilty verdicts in criminal cases. State Senate Bill 243, proposed by State Senator JP Morrell, a Black man from New Orleans, would allow voters to decide if Louisiana’s constitution should be changed to require juries in felony cases to return unanimous verdicts.

But Louisiana’s extremely powerful district attorneys, who no doubt love that non-unanimous jury verdicts help them convict and sentence people to prison, are not going out without a fight. And it’s that fight that I want to show you today. It’s one of the most remarkable examples of how our modern justice system was designed to charge, convict, and sentence African Americans as easily as humanly possible as a means of systemic oppression.

One of the leading proponents of the effort to maintain non-unanimous jury verdicts is Calcasieu Parish District Attorney John F. DeRosier. Let me tell you a little bit about DeRosier and his love of mass incarceration. A local defense attorney told me that DeRosier’s office files a notice of intent to seek life without the possibility of parole for all of the juvenile offenders in his parish who are eligible for re-sentencing under the Supreme Court’s historic decision in Montgomery v. Louisiana, which held that its ban on mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders applies retroactively. Another thing about DeRosier: One of his top prosecutors is Hugo Holland, who has been accused of misconduct so often in capital cases that one defense attorney called him “the face of Louisiana’s broken death penalty.”

So maybe it shouldn’t have surprised me when, in late April, DeRosier, a white man, decided to testify against the legislation to repeal non-unanimous jury verdicts — arguing basically that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it — saying “the concept has worked” for Louisiana. But what he said next set off a firestorm among Black lawmakers.

“I’ve heard a lot about this system being adopted as a result of a vestige of slavery,” DeRosier said. “I have no reason to doubt that. I’m not proud of that. That’s the way it started, but it is what it is. However, ladies and gentlemen, that was 138 years ago.”

Before I ever heard how Black lawmakers responded, DeRosier’s open, flippant, and callous admission that the way Louisiana does justice is indeed a vestige of slavery that he’s not proud of, but “it is what it is,” made my own blood boil.

You see, it is what it is not just because lawmakers in Louisiana made it that way to oppress African Americans by any means necessary over a century ago — it is what it is because Louisiana lawmakers have kept the system that way since then.

The very fact that a system was built in the shadows of slavery to oppress African Americans in the harshest, most unfair ways imaginable, is reason enough to completely re-evaluate the whole thing. But until now, over 100 years later, Louisiana has refused to do so.

Seething in righteous indignation, Louisiana House Representative Ted James, a Black attorney from Baton Rouge, struggled to hold himself together when it came time for him to respond to DeRosier. It’s best if you watch the exchange for yourself, but here’s what James said.

“Mr. DeRosier — I am so utterly offended for you to start your comments and say ‘I know that this was rooted in slavery, but it is what it is.’ And I needed you to hear that from me. And I wish you would look at me while I’m speaking with you. Because I think I deserve that kind of respect after you just disrespected me on this committee. You are elected to represent everybody and to admit that it started in slavery and say ‘it is what it is’ — I hope the people of your parish are listening. And if they aren’t, I’m going to make sure that they know what you said today. And I am utterly offended and for you to not even look at me in my face — this is a problem.”

It was incredibly brave and necessary for James to call out this casual admission from DeRosier of the fact that the law he wants to maintain is rooted in white backlash to Black folks being freed after slavery, but that he was just fine with it because it worked well for him.

The harsh fact of the matter is that this nation has not remotely come to grips with how many of its laws are rooted in slavery and bigoted oppression. After the Civil War, the United States never said, “Let’s examine every law and policy and system and structure we have to evaluate whether or not they were created as a tools of oppression.” That never happened.

And so here we are, over a century after Louisiana created laws to oppress one group more than all others, and district attorneys, the people who serve as the primary gatekeepers of America’s justice system, are still arguing that they are fine with vestiges from slavery in their system because it works for them.

It’s disgusting and we’ve gotta lot of work to do.

Clarification: In both Louisiana and Oregon, only 10 out of 12 jurors have to agree on a guilty verdict in felony cases. In Louisiana, non-unanimous verdicts are allowed in murder cases — but Oregon still requires a unanimous vote to find defendants guilty of murder.