Louisiana Wants to Jail Kids at Angola Prison’s Old Death Row

An upcoming court ruling could decide the fate of a plan to detain “problematic youth” at a facility that previously housed prisoners awaiting execution.

Update: On Sept. 23, Chief District Judge Shelly Dick ruled that children in Louisiana’s juvenile detention facilities can be moved to Angola, even as she wrote that it “will likely have deleterious psychological ramifications.” Read the decision here. Our original story follows.

A federal judge is expected to rule this week on Louisiana’s widely condemned plan to transfer youth detained in juvenile facilities to a unit that once served as the state’s death row.

In July, Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, announced a proposal to move approximately two dozen young people from the Bridge City Center for Youth, located outside New Orleans, to a building on the grounds of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola.

The facility slated to detain youth previously housed the state’s male death row prisoners until 2006, when they were moved to another building at Angola, which is also the site of the state’s execution chamber. More recently, the unit held incarcerated women who had been displaced by flooding at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women.

The governor’s announcement came just days after several young people escaped the Bridge City facility. The transfers, Edwards said, would begin as soon as possible.

Since then, the state has said the plan would allow for the transfer of any “problematic youth” held at the state’s secure juvenile facilities, which can detain children as young as 10 years old. The state says they’re establishing a temporary “Transitional Treatment Unit” at Angola to detain young people who need a “more restrictive housing environment,” while they work to develop a permanent housing site.

Youth sent to Angola, the state’s oldest and only maximum security prison, would remain under the authority of the Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ) and be held in a separate building from adult prisoners.

In August, several law firms filed a class action suit, challenging the proposed transfers as unconstitutional and in violation of a federal law mandating complete separation between incarcerated adults and youth. In a response to the suit, the OJJ said it had purchased “blackout” fabric that can be wrapped around the fenceline of the youth housing facility to create the required separation. The court has barred all transfers pending the judge’s decision, which is expected this week.

“This is not simply a location change,” said Nancy Rosenbloom, a Senior Litigation Advisor in the ACLU National Prison Project, which has joined the suit. The transfers will send a message to youth “that they will be going into the grounds of a maximum security prison, one of the most notorious in the country, and that this is how they will be treated.”

Community members say the plan is emblematic of Louisiana’s profoundly broken juvenile justice system, which violates its mandate to rehabilitate young people in its care.

In March, The Marshall Project, ProPublica, and NBC News, published an investigation into a Louisiana juvenile detention facility where teenagers were physically assaulted by staff, held in solitary confinement for weeks, and denied court-ordered services. Last month, the Louisiana Illuminator reported that job applicants flagged as high-risk for sexually abusing youth would still be considered for employment in OJJ’s secure care facilities.

As both sides await the judge’s ruling, children in OJJ custody are fearful of being transferred to Angola, said Kristen Rome, co-executive director of the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, a nonprofit law office that represents youth in the justice system. Rome said it’s unconscionable that Angola, once a plantation for enslaved Africans, is now poised to incarcerate children, especially considering the majority of children held in OJJ secure care facilities are Black

Youth could be sent to Angola for a variety of behaviors, including committing certain acts of violence against a staff member or possessing marijuana, according to a policy approved by the OJJ deputy secretary in August. The policy would allow for the transfer of up to four youth classified as seriously mentally ill and states that youth with significant developmental disabilities should be referred to the unit on a case-by-case basis.

“For our clients, they’re terrified. They are calling us all the time. Asking a lot of questions,” Rome told The Appeal. “It’s clear that no one’s communicating with them.”

Some staff inside the juvenile facilities have attempted to reassure children that they won’t be moved, because they’re “one of the good ones,” said Rome.

The class action suit was filed on behalf of detained youth, including Alex A., a 17-year-old at Bridge City who the state has recommended for transfer to Angola because of alleged disciplinary issues. Alex has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and takes medication “related to the nightmares he has from trauma,” his mother told the court in a statement. He will be released from custody no later than 2024.

“The fear and uncertainty around the move to Angola has caused Alex to tear out his hair and to not be able to sleep,” Alex’s mother said.

In a hand-written statement to the court, Alex wrote that he attends school at Bridge City, where he receives accommodations for a learning disability. Math is his favorite subject and he checks out books from the school library, he wrote. He has weekly group and individual counseling sessions, and meets with a social worker every two weeks. Alex speaks to his mother every day by phone for 15 minutes.

“It is the part of the day I look forward to the most,” he wrote. “She is the only one that really listens to me.”

Alex wrote that he and others at the facility are “terrified” of being transferred, and that “youth break down and shed tears because of the prospect of being moved to Angola.”

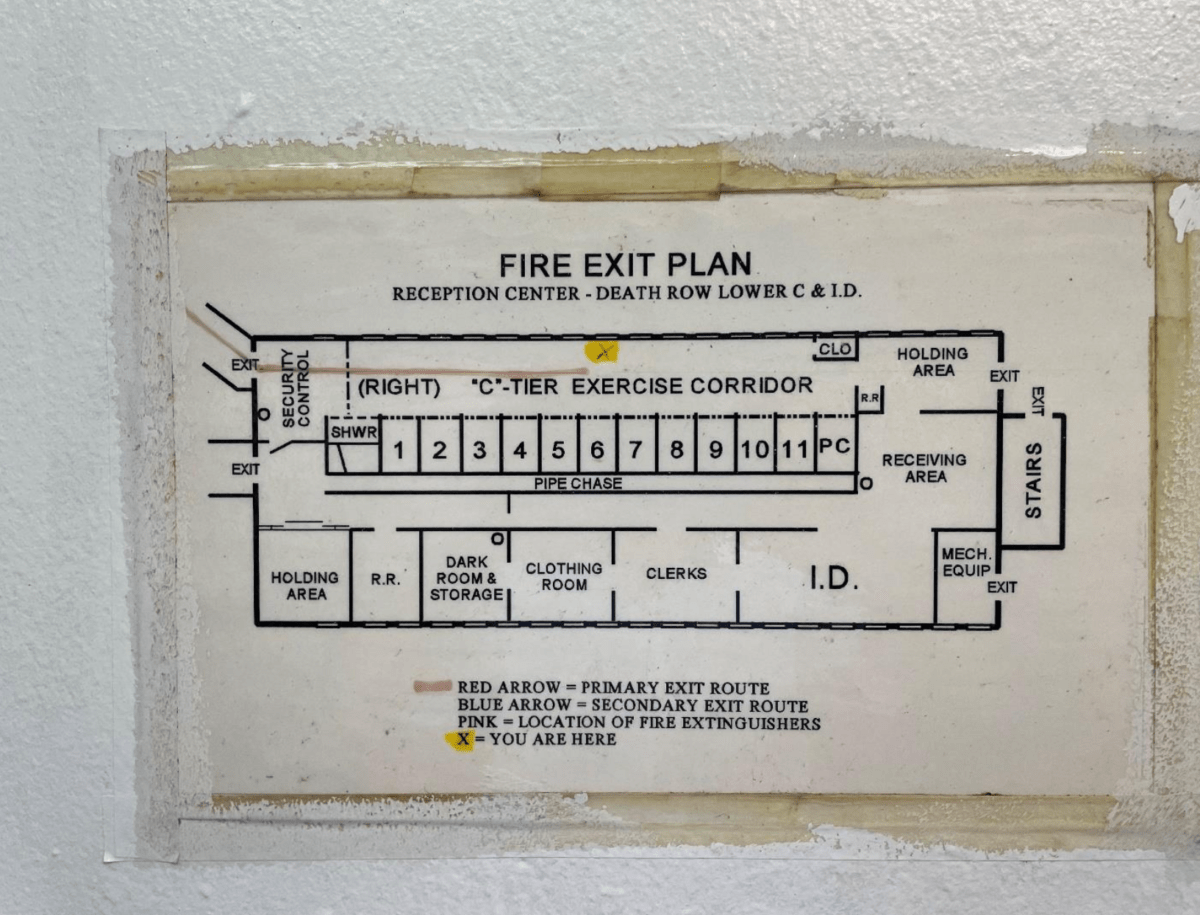

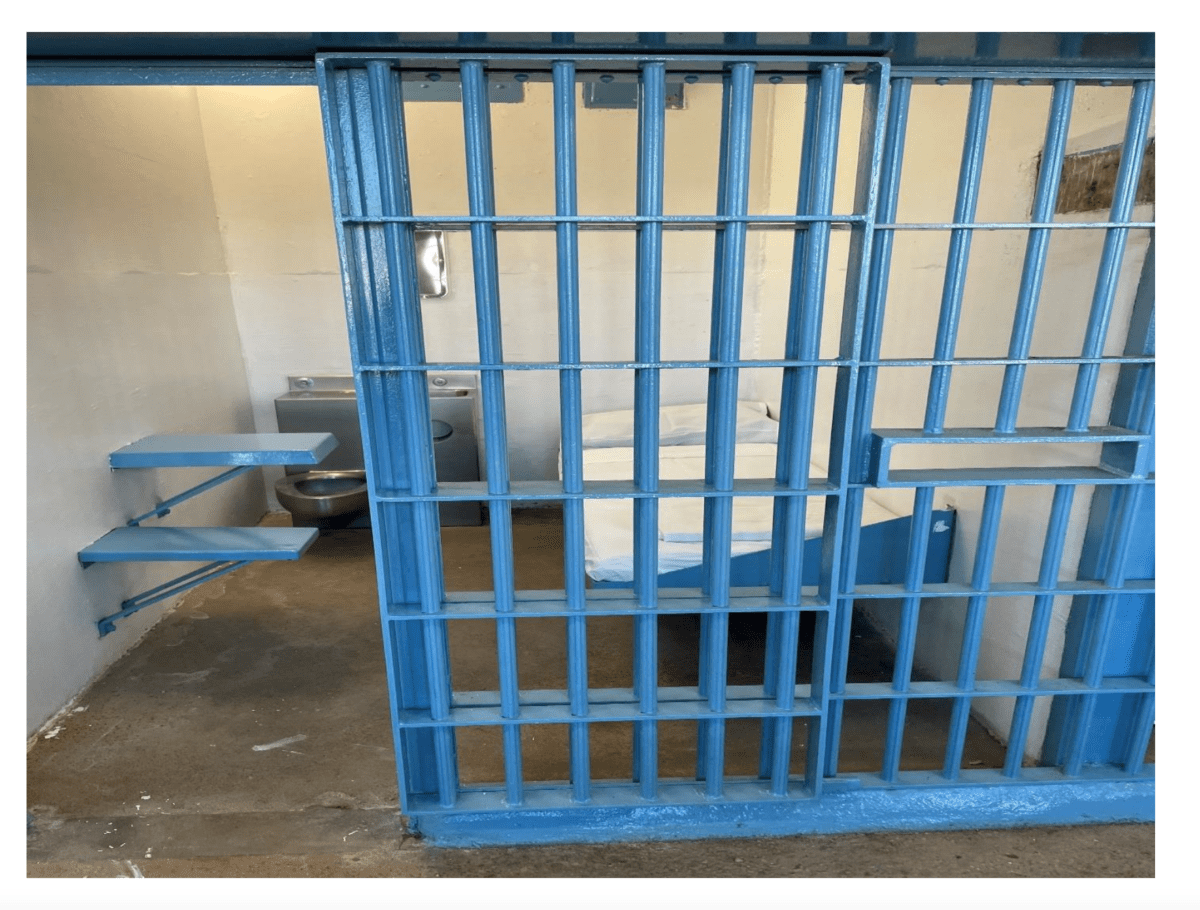

Young people transferred to Angola will be held in windowless cells with floor to ceiling metal bars, according to the court filing submitted by the ACLU and others. The facility “is going to scream ‘prison’ to young people,” Vincent Schiraldi, an expert for the plaintiffs and the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, testified in early September. During a tour of the unit before the hearing, Schiraldi photographed fire exit plans posted on the walls that stated, “Reception Center – Death Row.”

An OJJ spokesperson told The Appeal in an email that the facility has been renovated to accommodate young people’s needs, including the creation of spaces for education, visitation, and mental health services. The facility is more than a mile away from the nearest adult housing unit and youth “will not see nor hear adult inmates,” the spokesperson wrote. However, in the case of a life-threatening medical emergency, children would be treated at the hospital on the prison grounds, according to the spokesperson.

“As OJJ has said many times, this is not an ideal solution, but it is the best temporary solution we have available to us to keep our youth safe, to keep our staff safe, and to keep our communities safe after recent incidents,” the OJJ spokesperson wrote.

Opposition to the Angola transfer has been widespread. In July, an official with the U.S. Department of Justice sent a letter to the head of Louisiana’s juvenile justice agency, writing that the plan was “problematic” and could potentially violate federal law. Last month, advocates with Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children held a rally at the state capitol opposing the transfers. The state’s plan is “moving us backwards,” the group’s executive director and co-founder Gina Womack told The Appeal.

“They continue to perpetuate a damaging narrative about Black and brown youth to justify the ways in which they are mistreated and harmed,” she said.

In a letter to the governor and other state officials dated Sept. 20, leaders of Youth Correctional Leaders for Justice, a group of current and former youth correctional administrators, wrote that they condemn the plan “in the strongest possible terms.”

Young detainees engaging in “problematic behavior” do not yet have fully developed brains, and need education, support, and to “believe in their potential,” they wrote. This approach would lead to safer communities and lower recidivism rates; transferring young people to Angola, they warned, “will do the opposite.”

“Angola is perhaps the most infamous prison in the country, and exists in our national conscience as a quintessential harsh, merciless, and dangerous place for adults who may never be free again,” the letter’s authors wrote. “This lore is not lost on the children that Louisiana is now planning to send there.”