Commentary

My Son Died in LA County Custody. Months Later, His Death Hasn’t Been Counted.

A controversial death in Los Angeles this year underscores the broader failure of law enforcement agencies to keep accurate data on people who die in their custody.

On February 1, I received the worst possible news any mother could get: my only son, Stanley Wilson Jr., had passed away.

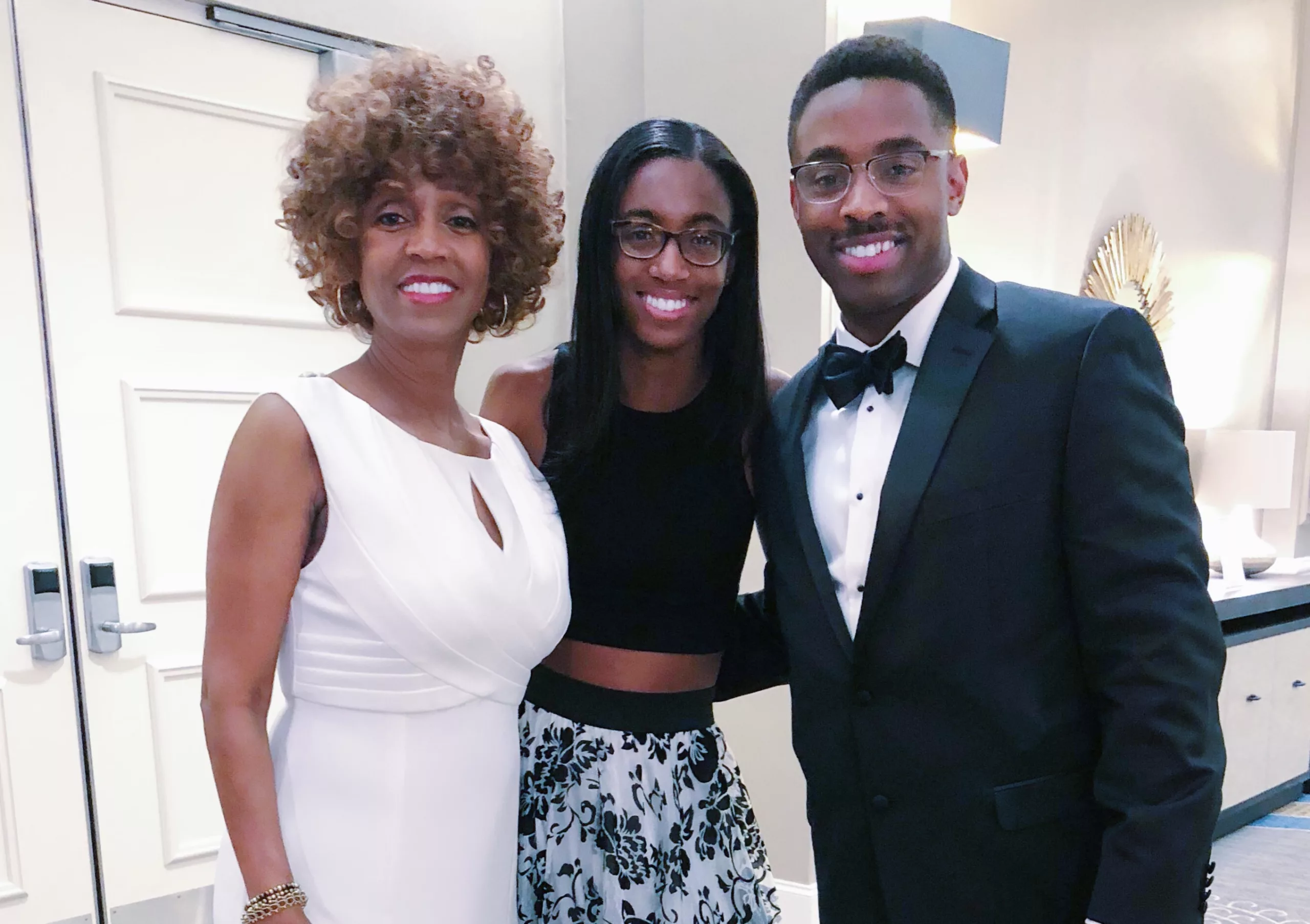

I was—and am—heartbroken. Stanley was a student leader, track star, and standout football player at Stanford University who went on to play in the National Football League for the Detroit Lions. After retiring from the NFL, Stanley struggled with mental illness and substance dependence, which ultimately led him on a path he was not destined for. He spent the final months of his life in the custody of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD). Stanley was only 40 years old when he died, and I learned from his post-mortem exam that he had suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

But there is still so much I don’t know about how my son died. LASD continues to provide conflicting accounts about the circumstances surrounding Stanley’s death. Despite clear signs of blunt force trauma on Stanley’s body, LASD has refused to answer even basic questions and ignored repeated requests to release CCTV footage capturing his final moments. This uncertainty has made the grieving process even worse than I could have imagined.

I am deeply concerned about the rising number of deaths in jails and prisons in the United States and Los Angeles specifically. Stanley is one of more than 30 people who have died so far this year in county detention facilities, according to LASD data, a rate of almost one life lost each week. But his death makes it clear that the official figure is an undercount.

LASD has not included Stanley’s death in its online database of in-custody deaths. Nor does it appear in the California Correctional Health Care Services database of in-custody deaths. Why is he missing from these records? Is Stanley one of the many whose deaths in custody will go uncounted?

When law enforcement agencies neglect to officially report deaths in their custody, they undercut transparency measures meant to help eliminate these incidents. By not counting Stanley’s death, LASD is not only erasing his death and the circumstances around it from public record. They are also making it harder to protect other incarcerated people from suffering similar deaths—whatever the cause may be.

The federal Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) requires states to report deaths during arrest or in law enforcement custody to the Department of Justice. But poorly implemented procedures, uncooperative police and corrections departments, and a general lack of enforcement have effectively derailed DCRA. Consequently, the public remains in the dark as our mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, sisters and brothers continue to die behind the concrete walls of mass incarceration.

In September 2022, a U.S. Senate subcommittee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs held a hearing on “Uncounted Deaths in America’s Prisons and Jails” to examine the DOJ’s implementation of DCRA. A high-ranking official in the U.S. Government Accounting Office testified that her agency had identified nearly 1,000 in-custody deaths in 2021 that states had not counted, technically in violation of DCRA. Senator Ron Johnson, a Republican, asserted that the Justice Department had “utterly failed” to meet the Congressional mandate set forth in DCRA.

The failure to count in-custody deaths deprives Congress and the public of information about the size, scope, and causes of this problem. The lack of information impedes the identification of custodial death trends and hampers corrective actions to improve medical and mental health care. Earlier this year, the Leadership Conference Education Fund and the Project on Government Oversight wrote that tracking in-custody deaths is “a critical step to achieving a just, free, and equitable society.” In my opinion, it is only the first of many necessary steps—literally, the least we could do to address this issue.

On Sunday, the families of loved ones who have died in LASD custody will gather outside Men’s Central Jail for a vigil to remember those we’ve lost and raise awareness about this issue. Together, we stand united by our shared pain and determination to bring about change. These tragedies have heightened our concern for the rising number of in-custody deaths in Los Angeles and the broader failures to track this problem.

We demand accurate reporting of in-custody deaths, whether by “natural causes” attributed to illness—possibly from neglect or inhumane conditions—or “unnatural causes” due to suicide, homicide, or injuries resulting from the use of force by deputies and other jail or prison staff. We demand justice, accountability, transparency, and a thorough overhaul of the Los Angeles County jail system.

A just society must extend its protection and care to all its citizens, regardless of their circumstances. Our loved ones deserved to be protected in life and counted in death—because their lives mattered, too.

Dr. D. Pulane Lucas is President and CEO of Policy Pathways, Inc., a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization based in Richmond, Virginia, that provides educational programming and developmental activities to individuals interested in becoming leaders in public policy, public administration, and international affairs. She is an associate professor (adjunct) at Reynolds Community College. She holds an MBA and MTS from Harvard’s Business and Divinity Schools, respectively, and a PhD in Public Policy and Administration from Virginia Commonwealth University’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs.