Los Angeles County Homeless Residents Say Sheriff’s Department Is Targeting Them

The ACLU of Southern California is suing the city of Lancaster and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department for excessively citing people living at desert homeless encampments in the Antelope Valley.

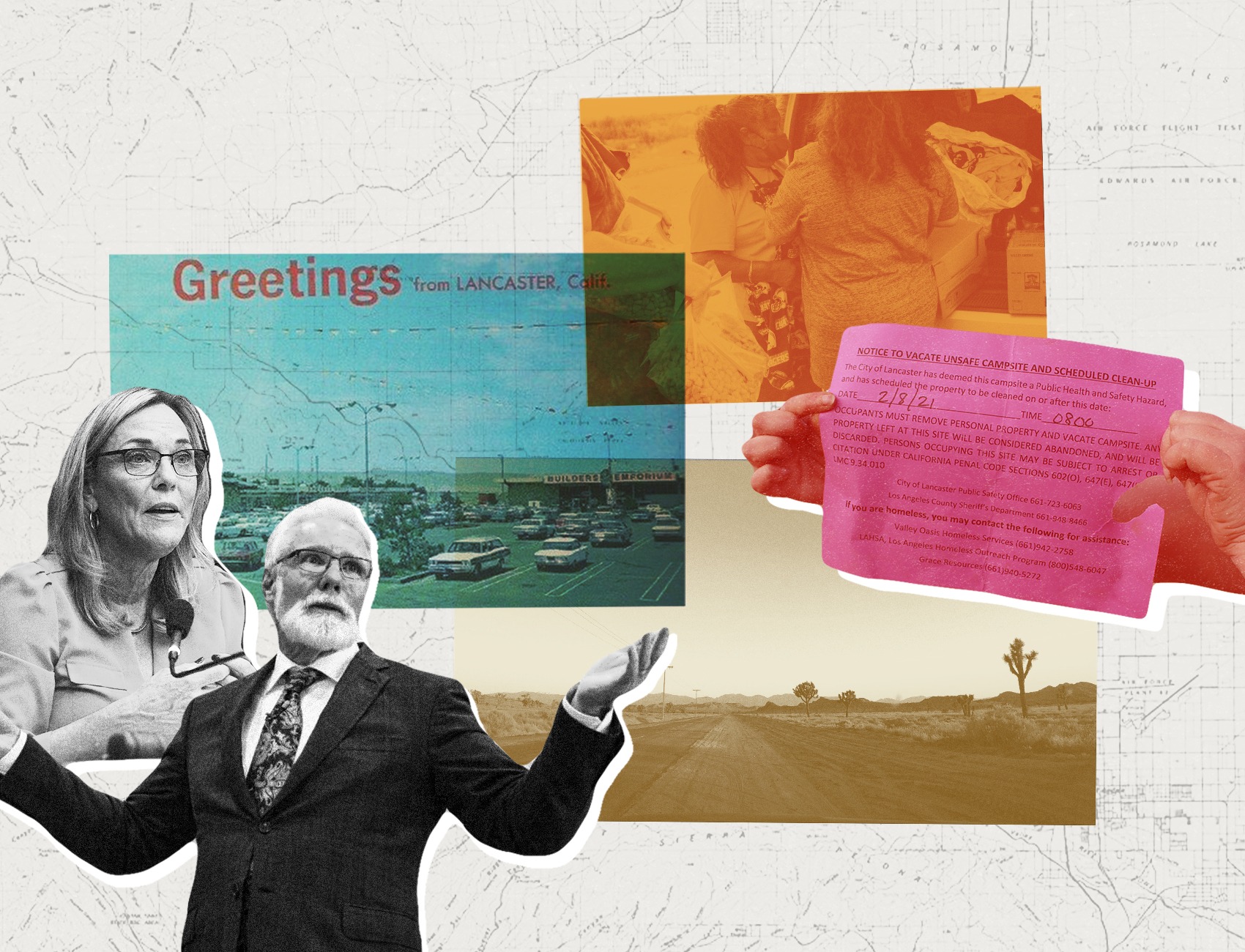

In March, Echo Park, a gentrified neighborhood in Los Angeles, made national headlines after police swept the area and removed about 200 people at a park encampment. But in the Antelope Valley, located just outside the city in the northern part of Los Angeles County, sweeps have been happening for years, sometimes with 72 hours’ notice or less. Unlike the Echo Park sweeps, they’ve often not been recorded or photographed, and have pushed people into the Mojave Desert.

Residents at one encampment in Lancaster told The Appeal that trekking into the desert with a truck, an RV, or merely a tent is a last resort. They said they have been pushed out of Los Angeles to Antelope Valley cities like Palmdale and Lancaster because of a lack of services, rising home prices, and evictions. But the Los Angeles County sheriff’s department has continued to clear encampments and cite people for municipal code violations.

Unhoused people in Lancaster make up about 1.3 percent of the city’s population, according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. However, they are the subjects of a quarter of all stops that result in citations issued by the sheriff’s department, which polices the area, and about half of the department’s stops to enforce the city’s municipal codes, the report said. ACLU SoCal, along with the University of California, Irvine, filed a lawsuit in February against the city and the sheriff’s department for a citation regime they say is “designed and enforced to punish poverty, in violation of the California Constitution.” The sheriff’s department did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment.

“Once the lawsuit dropped, the [administrative] citations almost pretty much stopped,” Ruth Sanchez, an ACLU Antelope Valley Chapter organizer, told The Appeal. “But that doesn’t mean the harassment has.”

In April, red tag notices indicating that residents had to leave appeared overnight on their belongings, Sanchezsaid. She did her best to connect people to services, and she routinely visits people in the encampments to offer food and connect them to county services, work that she says the deputies and Lancaster officials hardly do.

We hold both the city of Lancaster and the LA County Board of Supervisors accountable for this crisis.

Eve Garrow homelessness policy analyst and advocate at ACLU SoCal

The ACLU SoCal report cites Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris as partly responsible for a robust campaign to “criminalize and banish [the city’s] unhoused community members” through ordinances. When asked for comment, Parris referred The Appeal to a February statement from his office, which said city ordinances “do not target homeless people” and that the spike in homelessness in Lancaster did not have a “corresponding spike in funding to help them.”

“Lancaster has been reviewing the existing administrative citation program to ensure that it will benefit public health, safety and welfare, while providing persons who commit such offenses an opportunity to avoid criminal proceedings and possible convictions,” Parris said in the statement. “We will continue to support the program, with the goal of decriminalization and keeping people out of the system — including the unhoused.”

He suggested to local media that the city would continue to enforce city ordinances that affect homeless people. “Am I going to allow people to sleep wherever they want and try and get money from people who are shopping? That’s not going to happen,” he told the Antelope Valley Times.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, whose district includes Lancaster and Palmdale, was also cited in the ACLU SoCal report as responsible for the city’s treatment of unhoused people. Michelle Vega, communications director for Barger’s office, told The Appeal the office cannot comment because of the pending litigation.

“We hold both the city of Lancaster and the LA County Board of Supervisors accountable for this crisis,” Eve Garrow, a homelessness policy analyst and advocate at ACLU SoCal and one of the report authors, told The Appeal. “These people are constituents of both the city and the county. And both levels need to treat this crisis as the public health and safety crisis that it is for people that are unhoused. For so long now, they’ve pointed at each other when it comes to accountability but it has always been on both of their hands.”

Garrow said that the county has not responded to her request to meet with members of the Board of Supervisors about the report’s findings.

The lawsuit comes as organizers in the Antelope Valley are pushing to get the sheriff’s department out of their communities entirely. On March 4, a coalition of community organizations launched a campaign called Cancel The Contract, which asks the cities and schools of Palmdale and Lancaster to cancel their contracts with the Los Angeles County sheriff’s department and “reinvest dollars into a new vision of community safety and meaningful services for students and the community.” Educators and students last summer detailed experiences they had during school hours and on school property with sheriff’s deputies, including strip searches and harassment.

“I bought a stolen calculator. The campus cop arrested me for felony possession of stolen property,” reads one testimony from a former student. “I didn’t even know it was stolen. He didn’t care. I had a felony before I was 17, and the judge I was assigned to was known for keeping kids in jail. Not how a society should deal with their young.”

The coalition said it stands with the ACLU of SoCal’s demands and wants the nearly $28 million devoted to Lancaster’s contract with the sheriff’s department diverted to community services like long-term affordable housing, mental health and substance use services, and long term care. “Let’s envision a community beyond law enforcement,” the group said in a statement to The Appeal.

The Appeal asked the Board of Supervisors for comment on the group’s demands; Holly Mitchell, whose district includes portions of downtown L.A. and unincorporated areas like Baldwin Hills, was the only supervisor who responded.

“We cannot expect law enforcement to be the catch-all solution for the deeply nuanced social and economic challenges that push families into deep poverty,” Mitchell told The Appeal in an email. “Instead, a more collaborative approach is needed that includes community-based organizations and services to help ensure we are actually meeting the immediate and long term needs of our unhoused residents.”

The sweeps and citations make up a culture of constant fear and intimidation in the region, according to several unhoused people at an encampment. Although some have woken up to red tags telling them to leave the premises, some people have reported deputies showing up unannounced, with Lancaster city officials yelling at them to gather their belongings and shaming them for the current condition. Two people have reported sheriff’s deputies taking photos of them and their belongings without their consent and laughing.

“When the deputies come by, they say all these snarky things and make fun of you for being here,” said Aletha Johnson. “Once in a blue moon they’ll ask me how my dog and I are doing, but you know.”

Life in the Mojave Desert, away from critical infrastructure, is precarious. Temperatures can approach 0 degrees Fahrenheit in the winter and 120 degrees during the summer. At least two people at the encampment had come down with frostbite, Johnson said.

Gary Foss, who lives in a makeshift tent around his truck, said he and his wife were pushed like many others to the Antelope Valley because of loitering and panhandling ordinances in Lancaster. Their relocation resulted in immense tragedy. His wife suffered a heart attack in November, but the ambulance took over an hour to arrive, he said, given that their encampment is over seven miles away from the local hospital in the desert and Foss had to find someone with a phone near their makeshift home. She died before EMTs were on the scene.

On April 27, organizers with ACLU SoCal were able to get some cell phones to people in encampments in order to have them give public comments during Lancaster’s City Council meeting. Foss was one of two people to comment and shared the story of how sheriff’s deputies had forced him and his wife to move away from the city, which caused them to be completely isolated during their crisis.

Parris, however, appeared unmoved by the campaign to remove deputies from the city. In response to a public comment condemning the killing of Michael Thomas last summer, Parris grew visibly upset and asserted that “there is no intention of this council to replace the sheriff’s department.”

Organizers from the ACLU SoCal and Cancel the Contract coalition tell The Appeal that they plan to continue pursuing their campaign to get the sheriff’s department out of the Antelope Valley. They also plan to continue their overall push for a housing-first model and demand that the city of Lancaster and Los Angeles County provide restitution to all the people in encampments. They reject current programs like the city of Los Angeles’s camping sites with small-home villages in parking lots, and they demand short- and long-term solutions.

“We need to see this for what it is: a complete horrific public health crisis being orchestrated by two government entities,” Garrow told The Appeal. “This campaign to banish our most vulnerable people has gone on for far too long.”