Locked In, Priced Out: How Prison Commissary Price-Gouging Preys on the Incarcerated

The Appeal’s 9-month investigation uncovered prison commissaries’ exploitative, inconsistent systems with inside prices up to five times higher than in the community and markups as high as 600 percent.

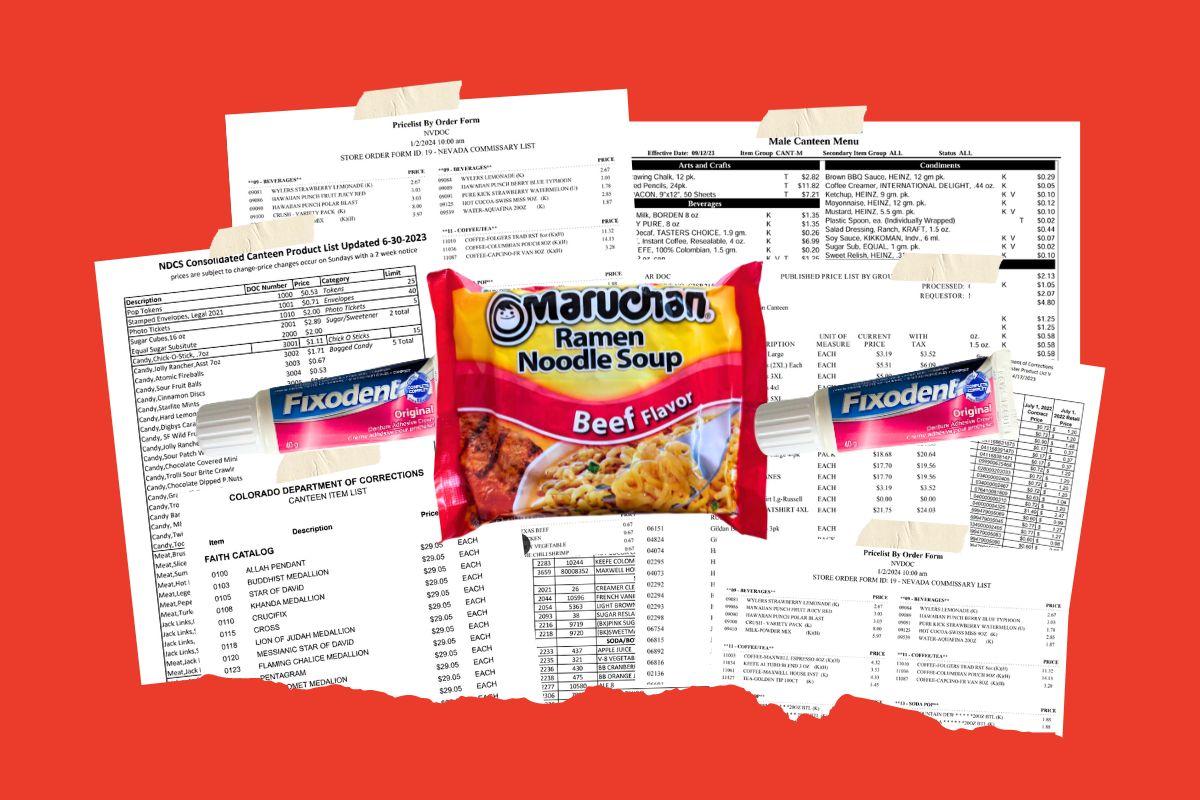

Today, The Appeal published Locked In, Priced Out, a project that includes a first-of-its-kind database of prison commissary lists from 46 states. This project also examines the availability, prices, and markups of products across several categories, including food, hygiene, and religious items. Taken together, the prices reveal an exploitative, inconsistent system that requires incarcerated people to purchase many necessities at high markups.

The Appeal’s investigation reveals that incarcerated people in many states are charged significantly more for essential items than those outside prison even though they typically earn pennies an hour—or no wages at all. The Appeal found prison prices up to five times higher than in the community and markups as high as 600 percent. This financial burden, which can cost hundreds of dollars per month, is often passed onto prisoners’ loved ones.

In just one example, Indiana prisons charged about $33 for an 8-inch fan, even though a similar item sells online for about $23 at Lowe’s. Incarcerated people in the state, who are often confined to dangerously hot prisons in the summer, can earn as little as 30 cents an hour, meaning it could take more than 100 hours of work to afford the fan.

The Appeal’s investigation also shows that prisoners can be charged vastly different prices for similar religious items, depending on their faith, with wide variations across states. In Connecticut, the Bible sold for $4.55, but the only Quran available for sale, The Noble Quran, cost $25.99.

Below, The Appeal uses this newly published database to explore the high costs of food, hygiene, and religious items in prison—which have sparked a movement to protect the consumer rights of incarcerated people and their loved ones.

Eating Inside

While prisons provide three meals a day, incarcerated people across the country regularly report being served inedible food in child-sized portions. As The Appeal has previously documented, this includes complaints of spoiled and rotten food and roaches on meal trays.

Jodi Hocking, the founder and executive director of the Nevada-based advocacy group Return Strong!, said her husband lost about 40 pounds after arriving in prison. She said he’s often served meals containing unknown meat.

“I’ll ask him, ‘What did you have for dinner?’” Hocking told The Appeal. “‘Today was rice chopped up with an unidentifiable something … I think it’s lunch meat. I think it’s bologna. No, maybe it’s turkey.’”

To supplement the meals provided, incarcerated people turn to the commissary to purchase food items like snacks, canned vegetables and meat, microwavable meals, beverages, desserts, and condiments. Even without access to kitchens or fresh food, incarcerated people often create meals using the commissary’s limited offerings, a creative practice that has inspired essays and cookbooks.

Of all the ingredients on commissary lists, ramen noodles are widely considered a universal staple of the prison diet.

The Appeal examined the price of a single packet of ramen on commissary lists in more than 40 states and found prisoners were routinely charged significantly more for ramen than they would be in the community.

One package of ramen goes for about 35 cents at Target, but many commissaries charged over 40 cents per package, according to documents obtained by The Appeal. Prices for identical products also differed greatly from state to state. Maruchan-brand ramen noodles cost 57 cents in Missouri prisons, for instance, but $1.06 in Florida prisons—about three times more expensive than at Target.

Prices can differ within states, too. In Arkansas, a package of chicken-flavored ramen sold for different prices at almost every prison canteen in the state. At one prison, the item cost 29 cents and at another 49 cents.

Some of the highest-priced ramen in the country was sold at commissaries run by Keefe Group, which is controlled by the private equity firm HIG Capital. HIG’s portfolio also includes the for-profit corrections healthcare company Wellpath and prison dining company Trinity Services Group. As The Appeal has previously reported, incarcerated people and their loved ones have accused Wellpath of providing grossly inadequate healthcare. Imprisoned people have also alleged that Trinity Services Group serves meager portions of inedible food. Keefe Group did not respond to requests for comment.

The dismal quality of prison-provided meals often forces incarcerated people to buy food at the commissaries to stave off hunger.

“Incarcerated people are using their hard-earned money and their family’s hard-earned money to buy things to help them survive,” said Wanda Bertram, communications strategist for Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy group. “It’s cruel enough that prisons are making people do this. And it gets even worse when you know private companies owned by private equity firms get involved and look for ways to make as much money off of it as possible.”

Staying Healthy & Cool

In some states, incarcerated people pay premium prices for fans, even as many are confined to prisons without air conditioning.

In Kansas, it would have taken an incarcerated person, who can earn as little as 45 cents a day, more than 40 days to afford a 6-inch fan and more than 100 days to afford an 8-inch fan. A spokesperson for the Kansas Department of Corrections told The Appeal in an email that “most KDOC facilities are air-conditioned or have air-handling systems for improved airflow.” Incarcerated people who are “housed in units that lack climate control” and have no more than $12 a month in their spending account are provided a state-issued fan.

In Delaware, an 8-inch fan at Sussex Correctional Institution cost almost $40. In Georgia, where most prison labor is unpaid, a 10-inch electric fan was marked up more than 25 percent and cost about $32. In Mississippi, an 8-inch fan was sold for $29.95. Despite the brutal summer heat, most of the state’s prisons lack air conditioning in their housing units. Fan prices are just one of many high costs incarcerated people face in hot prisons. Last June, in Texas, the state and commissary vendor raised the price of water by 50 percent.

Many incarcerated people also rely on commissaries to buy over-the-counter medications, shampoo, and other essential supplies. Certain hygiene items, such as toilet paper, tampons, maxi pads, or soap, may be provided free of charge. Still, advocates say the quality of those products is poor, and the quantity is often insufficient.

The Appeal found that incarcerated consumers in many states are charged more for essential hygiene items than people in the community, including items generally used by older people. In 2022, about 15 percent of the federal and state prison population was 55 and older, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

In Idaho, the commissaries sold Fixodent denture adhesive for $12.28; Target sells the same item in a pack of three for only a few dollars more. A spokesperson for the Idaho Department of Corrections (IDOC) told The Appeal in an email that the state’s commissary vendor, Keefe Group, sets prices at the beginning of its contract, and IDOC must approve any increases.

“IDOC staff routinely check commissary prices against convenience store prices for similar products as it’s a more appropriate economic comparison than major retail or wholesale outlets,” the spokesperson wrote. “Commissary vendors tend to be smaller operations than the big box stores in the community and as such, are likely to procure the goods at a higher price, have a smaller inventory, and in turn, have slightly higher prices.”

In Oregon, prison commissaries sold eight hearing aid batteries for $11.49. However, Target sells an eight-pack for $6.50. Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC) policy states that items are marked up at least 20 percent unless otherwise specified.

An ODOC spokesperson told The Appeal in an email that hearing aid batteries are free to people who receive hearing aids from the department and that individuals who need hearing aid batteries to attend a program, service, or activity can request them.

The prices for reading glasses differed significantly among states, further illustrating the pervasive inconsistency of commissary prices.

In Vermont, a pair of reading glasses cost more than $15 in prison, about five times the price a shopper would find at Walgreens. The Department of Corrections contracts with Keefe Group for commissary services.

A Vermont Department of Corrections (VDOC) spokesperson told The Appeal in an email that “commissary items are often more expensive than the price of items in the community” but said they do not have enough information to “speak to the specific discrepancies.” There is currently no policy that sets a cap on commissary prices, according to the spokesperson.

The VDOC dedicates 29 percent of commissary revenue to “recreational and wellness opportunities for individuals incarcerated at the facility,” the spokesperson said.

States often direct at least a portion of commissary sales to Inmate Welfare Funds, which can be used to purchase books, recreational equipment, and other items for incarcerated people. In Indiana, 32 percent of the markup on each item funds recreation at its prisons, according to a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Corrections. Similarly, in North Carolina, all profits from commissary sales “go into the Inmate Welfare Fund for programs and equipment that benefit the offender populations,” the department’s communications director wrote in an email to The Appeal. In Alaska, many items are subject to a 3 percent “Inmate Welfare Fund” surcharge. (In some states, there have been allegations that corrections officials have misused Inmate Welfare Funds.)

Keeping the Faith

Although less frequently sold than food or hygiene products, some commissaries sell religious items. (Depending on the facility, prisoners may obtain religious items from their commissary, an approved vendor, from the prison for free, or from an outside organization also for free, or some combination of those options.)

Among these prison commissaries, The Appeal found that people were sometimes charged more inside prison than they would be if they shopped in the community. Prices also varied from state to state and, in some instances, from religion to religion, with Muslim prisoners paying particularly hefty prices, according to The Appeal’s analysis.

For instance, in Virginia, a Christmas card cost 80 cents, but a Ramadan card sold for $2.33. The Virginia Department of Corrections declined to comment.

In Vermont prisons, the Quran cost $27.45, about $11 more than the Bible sold at that state’s commissaries. In Connecticut, the Bible sold for $4.55, but The Noble Quran, the only Quran available for sale, cost $25.99. A spokesperson for the Connecticut Department of Corrections told The Appeal in an email that books sold through the commissary “are determined by the contracted publisher” and that incarcerated people are “provided free copies of the Quran, Bible, the Torah, and various other religious text as needed.”

Many incarcerated Muslims also seemed to be overcharged for kufi caps. Outside of prison, the traditional head covering worn by some practicing Muslims can be purchased for under $3. But Muslim prisoners were charged more than $7 for a cap on average, across all states examined. In Indiana prisons, a cap cost more than $12.

A spokesperson for the Indiana Department of Corrections told The Appeal in an email that outside organizations occasionally donate kufi caps.

In Virginia, a person earning the state’s minimum wage for incarcerated workers would have to work:

Profiting From Prisons

There are few consumer protections for incarcerated people and their families, with some states raking in double-digit commissions from products sold at prison commissaries.

In Florida, for instance, a five-year $175 million contract with the for-profit company Keefe Group gives the Department of Corrections a 35.6 percent commission on all marked-up items. (Those sold at or below cost are not subject to the commission.)

In Kentucky, under the terms of its contract with Union Supply Group, the state’s Department of Corrections receives a 16 percent commission from “Inmate Canteen and inmate vending.”

Prisons and private vendors also benefit from high markups.

Based on documents obtained by The Appeal, markups—the amount charged above what the seller paid for the item—vary significantly across the U.S.:

- In Georgia prisons, a denture cup was marked up over 600 percent. Peanut butter had a markup of more than 70 percent.

- In Missouri, ramen noodles and Tums antacids were marked up more than 65 percent.

- In Arkansas, all food items “deemed healthy” and over-the-counter “health aids”—including reading glasses and denture adhesive—were marked up 40 percent, and all remaining items were marked up 50 percent.

- In Wyoming, departmental policy set a 20 percent markup on “luxury goods,” including reading glasses and shower shoes, and a 30 percent markup on so-called “premium goods,” including ramen and Velveeta macaroni and cheese. There is no markup on “basic hygiene items” or religious items.

In addition to high markups, many incarcerated consumers also have to pay sales tax, as well as fees related to their incarceration. In Iowa, for instance, prisons add a 6 percent “Pay for Stay” fee to most commissary items.

“Whether it is a private, external contractor or a state-run contractor, there is still a profit model built in,” said Priya Sarathy Jones, deputy executive director for the Fines and Fees Justice Center, an advocacy organization dedicated to reducing or eliminating costs related to arrest, prosecution, and incarceration. “Private companies and [government] entities are profiting off of low-income people.”

Moves to Cut Markups

The tide against high prices and markups is slowly changing, said Jones.

“I do think what we are seeing is more and more of a recognition that this particular population—those who are incarcerated and their families—are being preyed on,” she said.

Illinois has long had a state statute capping prison commissary markups at 35 percent for tobacco products and 25 percent for other products. And last year, several other states began to reign in the practice of high markups, though advocates say there is still much more work to be done.

In July 2022, the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) eliminated markups on hygiene items, previously set at 19 percent for most products. This year, the department also reduced the markup on food items to 14 percent, an MDOC official told The Appeal in an email. These changes were made to “partially offset inflationary product price increases,” he wrote.

In California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom recently signed the BASIC Act, which caps markups in prison commissaries at 35 percent until Jan 1, 2028. Items had previously been marked up between 63 and 200 percent, according to the office of California state Senator Josh Becker, who introduced the bill.

The cap on markups has made a significant difference, said Warren Hands, a supervising parole success advocate with UnCommon Law, a law firm that assists and advocates for Californians navigating the state’s parole system.

“When the prices went down, guys were able to exhale,” he told The Appeal.

But Hands said more reforms are still needed. He noted that California’s 35 percent cap on markups is still higher than in many other states. In addition to further reducing prices, incarcerated workers’ pay must be increased, he said. While incarcerated, Hands worked various jobs—at the boot factory, in the commissary, on the yard, and in the kitchen. He said he never earned more than 75 cents an hour.

Nevada also recently reduced markups. Last year, Republican Governor Joe Lombardo signed legislation that, among other reforms, eliminates markups on hygiene items.

Advocates have been working with the Department of Corrections to build on that success in hopes of bringing prices down even more, said Nicholas Shepack, the Fines and Fees Justice Center’s Nevada state deputy director. Buying food from the commissary is essential, said Shepack. Aramark provides meals to Nevada prisoners and Keefe Group runs its prison commissaries.

“The commissary food supplements what has been described by hundreds and hundreds of incarcerated people as extremely poor, low-quality food,” he said.

Change can’t come soon enough for Hocking, whose husband is incarcerated in Nevada. She said that ensuring he has basic necessities, including items from the commissary, costs her more than $1,000 a month and has put her in a precarious financial situation.

“The obvious answer is, ‘Well, stop sending him money,’” said Hocking. “But I’m not sending money for drugs or a gambling problem. I’m literally sending money just to help him survive.”