Newsletter

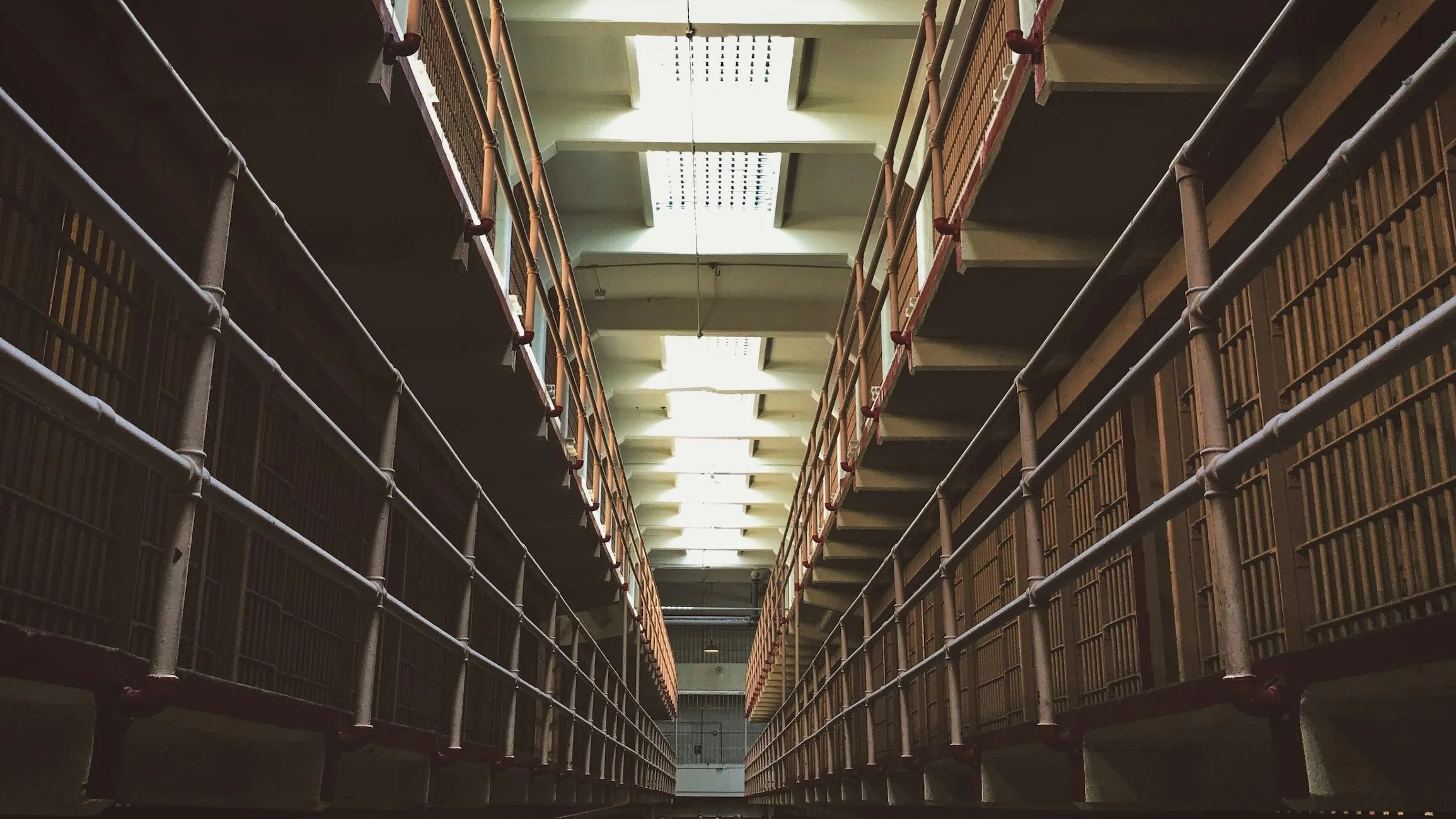

Living Among the Innocent on Death Row

Six people on North Carolina’s death row have been found innocent since I’ve been here.

When I got to Death Row, I expected that everybody would be just like me. People with multiple murders. People who had killed in cold blood. The absolute worst of the worst. I was prepared for that. But what I was not prepared for—what never even crossed my mind as a possibility—was that there would be innocent people on Death Row.

There have been six people in North Carolina who have been found innocent and who went home after spending years on Death Row since I’ve been here: Alfred Rivera, Alan Gell, Jonathan Hoffman, Levon Jones, Edward Chapman, and Henry McCollum. I didn’t really know the first five because I was on lock-up for seven and a half years and didn’t get out until 2004. Hoffman, Gell, and Rivera were already gone by then, so I never met them. Jones and Chapman I saw, but we didn’t talk much. I didn’t know anything about their cases, so when they left it didn’t impact me much. But Henry McCollum changed my perspective.

I knew Henry. We weren’t close friends, but we lived on the same unit for at least ten years. He was quiet, slow, and very timid. I heard about his case—he had been charged with raping and killing an eleven-year-old girl. He claimed he was innocent, but I didn’t believe him. I thought he was a sick pervert in denial and I didn’t have any sympathy for him. But to my utter disbelief, around the end of August 2014 people started saying that Henry was getting ready to go home. His case was being brought before the Innocence Inquiry Commission, and they were saying that he really was innocent.

I started to take an interest in his case and talked to him. I found out that his brother, Leon Brown, who was also convicted and originally sentenced to death along with Henry in 1984 but had then gotten resentenced to life, had filed a complaint with the Innocence Inquiry Commission. Actually, another inmate had filed on his brother’s behalf, because his brother could hardly read or write. The commission investigated the claim and, for the first time, sent DNA evidence to be tested. Lo and behold, the DNA implicated another man who had been arrested for a similar murder and rape less than a month after Henry and his brother had been arrested. That man, Artis Roscoe, had been sentenced to death and had spent years on Death Row with Henry and his brother. He had even befriended them, knowing all along that they were innocent.

It was only because of Leon Brown’s petition that both brothers were eventually exonerated. The commission only investigates claims of innocence from people who have exhausted all their appeal options in court. A person on Death Row can never file a petition to the commission, because as long as a person is on Death Row, they are still under appeal. When a Death Row prisoner has no more appeal options, he is executed. So Henry could’ve never filed a petition to the commission, and therefore the only way he was able to have his case heard was because the commission was hearing his brother’s case and they were codefendants.

When I found out that Henry was innocent, I felt guilty because I had condemned him along with everyone else. It broke my heart as I tried to put myself in his shoes and imagine what it had been like for him for over thirty years—accused of a horrible crime that he didn’t commit. And his brother was only fifteen years old. With a crime like that, he was attacked and raped repeatedly over the years. I sat in my cell, and I cried for those brothers and what they went through. There’s no compensation for that. Nothing that can ever restore what was taken from them.

Henry McCollum was the sixth person who went home from Death Row after being wrongfully convicted since I’ve been in Central Prison. I realized that the system was flawed. No, that’s an understatement. It was broken. I already knew about Elrico Fowler’s case. He had told me about his innocence around 2013. This blew my mind because I met him in 1998 and we had become good friends. Yet for fifteen years he had never told me he was innocent. I didn’t understand it at first. Why didn’t he tell me? Because he thought I already knew. I went back through my mind and recounted the hundreds of conversations we’d had and with the knowledge that he was innocent in mind, they all started to take on a different meaning. He had been telling me this the whole time, but I wasn’t listening. I said to myself, “Alim, you’ve got to start paying attention to what people are really saying.” Since then, I’ve met several people on Death Row that I believe really are innocent. I think about all the people that drive by this prison every day—right in the heart of Raleigh—who have no idea that innocent people are behind these walls. Innocent people sitting in cells on Death Row waiting to be executed. Innocent people feeling utterly helpless as the gigantic machine that is the justice system churns away with pitiless routine.

Once I woke up to the reality that there are innocent people living with me here on Death Row, I started to see things differently. I’ve learned that they can adapt to their environment and survive. They learn the rules, mimic some of the conduct of those around them. Even develop some of the attitude, the facial expressions, and tone. They can learn to look tough, act tough, blend in, and seem unfazed. But the fact is, you can’t disguise yourself as a killer when you are surrounded by them. You’ll get sniffed out like a virgin in a room full of pimps. And that’s facts. My friend Sabur is innocent. The man ain’t never killed nobody. One of the reasons I know is because when you do actually kill someone you lose an innocence that you can never regain. And just talking to Sabur sometimes reminds me of the innocence that I once had. It’s a way of seeing the world that you never appreciate until it is lost. And once it’s lost, it never comes back. When I talk to my mom I still can see and hear that innocence in her, and it’s also in Sabur. They don’t even know it’s there. But I do.

I feel a moral responsibility to do something. How can I not? I’m supposed to be here. I know what I deserve. I’m guilty. But when I look around and I see people in here like Elrico and Sabur, it’s like, WAIT! Hold up! These men aren’t supposed to be here. I can’t just act like nothing is happening. I ain’t built like that. The least I can do is call out for help. The least I can do is scream at the top of my lungs, saying, “Hey! There are innocent people in here! They aren’t supposed to be here. Somebody please help!” So that’s what I’m trying to do with my music. I’m making some noise to bring attention to the fact that Elrico and Sabur are innocent. There are others too, but you’ve got to start somewhere.

There are four reasons for me to be making music. Either I’m doing it for fun, or I’m trying to make a difference in the world with my talent, or I’m doing it for money, or I’m doing it for fame. While there’s nothing wrong with any of these motives, I’m primarily motivated by the first two. I love writing and reciting rhymes. It’s my passion. It’s fun, and it’s an ability that Allah gave me. But at the end of my life, I don’t want to feel like I’ve squandered what Allah has given me. I want my life’s work to have real meaning. So that when I stand before my Lord and He asks me what I did with what He gave me I can say I used it to help people, and I pray that He will be pleased. And what greater meaning or nobler thing can you do than to save a person’s life? Allah says in the Qur’an that to kill a person is like killing all of mankind, and to save one life is like saving all of mankind. Inshallah, if I can use my music to literally save a man’s life on Death Row, then that’s in the ultimate service of Allah. I may not accomplish this, but at least my Lord will know that I spent my time trying to make a difference and I pray that He will forgive me for the wrong I’ve done in my life.

From Rap and Redemption on Death Row: Seeking Justice and Finding Purpose behind Bars. Copyright © 2024 Alim Braxton and Mark Katz. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.

In The News

A company that manufactured drugs used in federal executions will no longer produce the compound, according to a letter sent by the company’s CEO to Connecticut state legislators. The Trump administration used pentobarbital manufactured by the company during an execution spree that killed 13 people in 2020 and 2021. [Daniel Moritz-Rabson and Lauren Gill / The Intercept]

Police have torn off hijabs worn by Muslim women at pro-Palestinian protests across the country, including demonstrations at Arizona State University, Columbia University, Depaul University, and Ohio State University. The First Amendment protects women who wear hijabs for religious expression, but few safeguards exist to ensure police respect this right while making arrests. [Saliha Bayrak / The Nation]

New worker safety regulations to protect indoor workers from extreme heat in California are in jeopardy after the state’s Occupational Safety & Health Standards Board exempted prisons and other correctional facilities from complying with the safeguards. Many prisons and jails lack adequate air conditioning, leaving incarcerated people and correctional officers vulnerable to heat-related injuries. [David Sherfinski / Context]

The death of a woman sexually abused by police in Stoughton, Massachusetts, was a homicide, according to a pathologist hired by the deceased woman’s family, contradicting the state medical examiner’s ruling that the death was a suicide. Three former Stoughton police officers abused the woman, Sandra Birchmore, while she was a teenager participating in a police youth program. [Laura Crimaldi / Boston Globe]

A man waited more than 20 years for a Georgia court to rule on his motion for a new trial after court employees misplaced his filing. The delay prevented Leslie Singleton, who was convicted for felony murder when he was 17 years old in 2001, from presenting his case to appellate courts for more than 22 years. [Leslie Gross / Atlanta Journal-Constitution]